Amidst the war in Ukraine, Russia spins tales of language suppression and ethnic dominance. Through robust evidence, we dismantle these falsehoods and affirm enduring resilience of the Ukrainian identity of the East of Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine, particularly in Donetsk and Luhansk regions—part of Ukraine commonly referred to as Donbas—has been swarmed by misinformation and misconceptions about the local population. Among the prevalent myths pushed by Russia are claims that people in Donbas never spoke Ukrainian, that the Russian language was threatened, and that the region is predominantly populated by “ethnic Russians”. In this article, we aim to debunk these myths with facts and evidence, shedding light on the linguistic and ethnic diversity of the Donbas region, as well as its tragic history of Russification.

Myth 1: "People in Donbas never spoke Ukrainian"

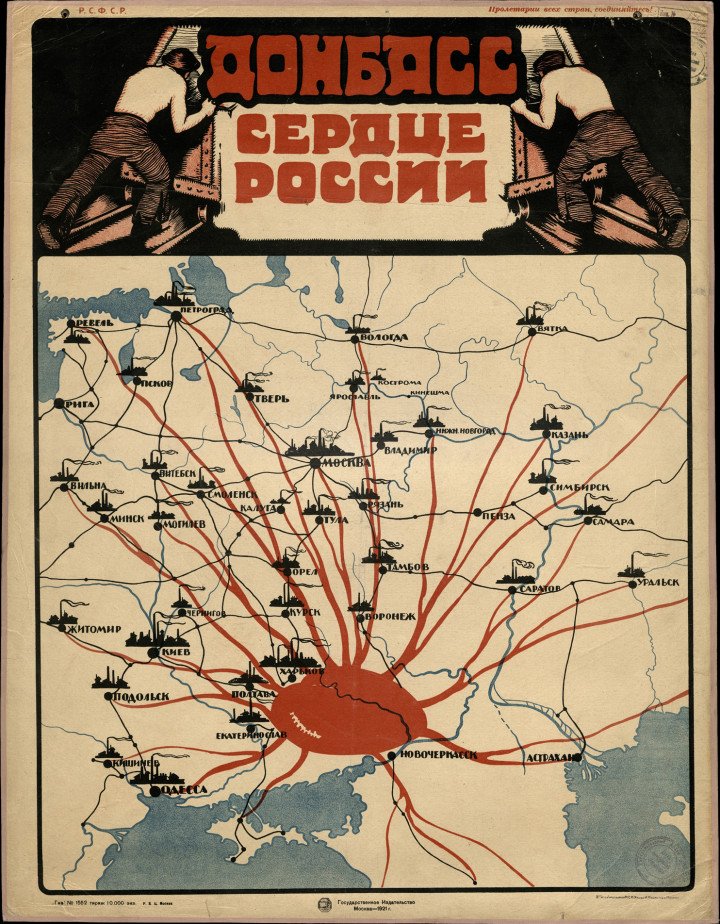

In some Russian propaganda narratives, Donbas appears as a region that has always been disloyal to independent Ukraine and gravitated towards Russia. In 2014, the Russian invaders counted on this factor, planning their adventure with "Novorossiya", where, apparently, it was “necessary” to protect Russian-speaking citizens.

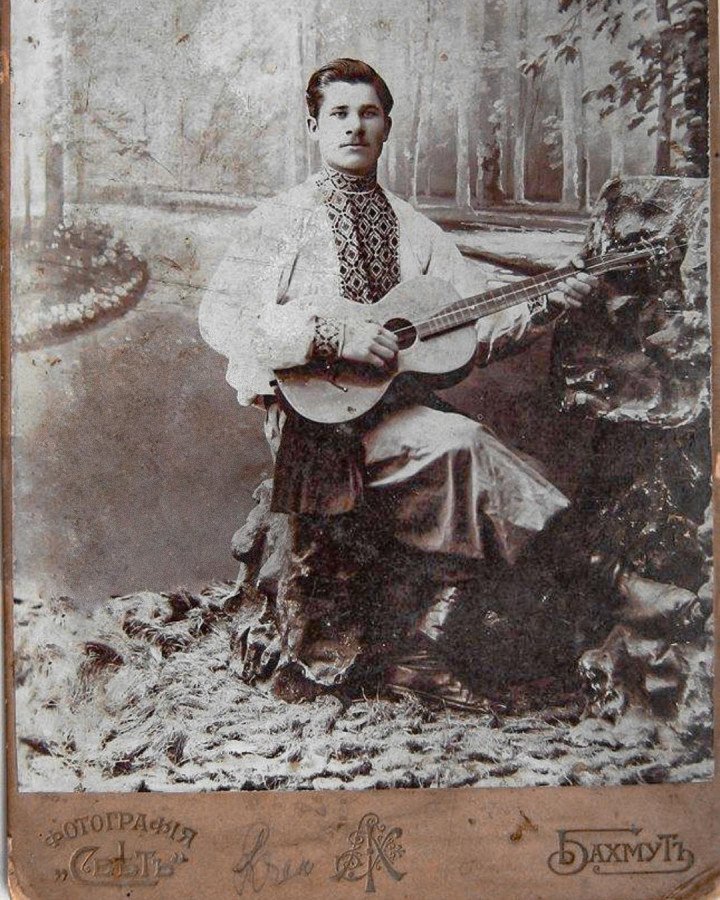

Contrary to popular belief, the history of Ukrainian language has significant presence in the Donbas region. While Russian is widely spoken, especially in urban areas and industrial centres, Ukrainian has deep roots in the cultural and linguistic heritage of Donbas. Historical records attest to the use of the Ukrainian language in literature, education, and everyday communication throughout the region's history. To understand the spread of the Russian language in Donbas, we must understand the bloody history of the Russification of these lands.

Where and when did the Ukrainian language begin to be banned? Starting from the late 17th century, there were prohibitions on printing books in Ukrainian, and Russian Empire authorities confiscated Ukrainian primers from church services and schools. With the East of Ukraine becoming part of the Russian Empire, the Ukrainian language and culture as a whole were under censorship and enforced Russification. These and many other measures, implemented to different extents and with varying degrees of success, were enforced across most of the territory of Ukraine. In the East of Ukraine, russification was also advanced by educational reforms implemented by the USSR. Russian was introduced in local schools in 1938.

Only about a hundred years ago, Russian speakers in Donbas were a minority. This is evident even from the census conducted by the Russian Empire itself in the 19th century, which showed that 70% of the population in the Donbas region spoke Ukrainian, or “little Russian”, as it was referred to by the Empire authorities. This number dramatically declined during Holodomor, the famine-genocide, as the region ranked amongst the most affected by it. Dying Ukrainian towns and villages were later repopulated by the USSR – something that has happened and will happen in history again and again, as it is a settler-colonial tactic. Almost 100 years later Russia will use this tactic in Mariupol.

However, despite such extensive linguicide, the Ukrainian language and traditions prevailed in Donbas. Some of the most prominent Ukrainian intellectuals came from or lived most of their lives in the region: Vasyl Stus, Volodymyr Sosiura, Mykola Rudenko, Oleksa Tykhyy to name a few. As the region suffered so much from Russification, Donbas always had a prominent political resistance that pushed for the preservation of the Ukrainian language despite Soviet efforts to sensor everything Ukrainian.

Myth 2: "Russian language was threatened in Donbas"

While there have been efforts to promote Ukrainian language and national identity in Ukraine, there is no evidence to suggest that the Russian language was ever under threat in Donbas. Both Ukrainian and Russian have coexisted in the region for centuries, with many residents being bilingual or multilingual. Language policies in Ukraine have aimed at promoting Ukrainian as the state language while respecting the linguistic rights of minority groups, including Russian speakers.

People who believe this propaganda point often refer to the Language Law, which obliges all citizens to know the Ukrainian language and makes it a mandatory requirement for civil servants, soldiers, doctors, and teachers. There have been some serious claims that the Russian language became persecuted, hence Russia had to invade in order to protect Russian speakers. However, Russia invaded in 2014, and the law only took effect in 2019. It is clear that the law was therefore never a pretext for the invasion, but rather a measured and necessary consequence. Furthermore, at no point did the law prescribe any changes to the Criminal Code of Ukraine.

Another fact that Russian propagandists often avoid is the existence of the 2012 law On the principles of the State language policy. Just two years before the invasion, the Russian language was granted a regional language status, which in actuality was not in compliance with the Ukrainian constitution, violating Article 10. This was indeed confirmed by the Constitutional Court in 2018. To this day, there is no evidence that the new state law on the functionality of the Ukrainian language regulates private communication.

Protection of the Ukrainian language indeed became more regulated in recent years; however, it happened after the full-scale invasion. Measures such as restrictions on Russian books and music were implemented to give space to Ukrainian ones, as an effort to fight centuries of linguicide of the Ukrainian language which is extensively covered in this article. Moreover, the Russian propaganda narrative of Russian speakers being forced to speak Ukrainian has no validity. Since the full scale invasion there has been a significant decline of use of Russian as preferred language. Many Ukrainians are bilingual as a default, however Russia has used this as one of the main reasons for the invasion, both in 2014, and in 2022. The conscious positive shift of Ukrainian public using Ukrainian as default is a strong point to debunk this narrative once and for all.

Myth 3: "Donbas is predominantly populated by ethnic Russians"

Donbas is ethnically diverse, with Ukrainians, Russians, and other ethnic groups coexisting in the region. The ethnic composition of Donbas has evolved over centuries due to historical migrations, industrialization, and cultural exchanges. Many residents of Donbas identify as both Ukrainian and Russian, Ukrainian and Urum, Ukrainian and Jewish, reflecting the region's complex identity.

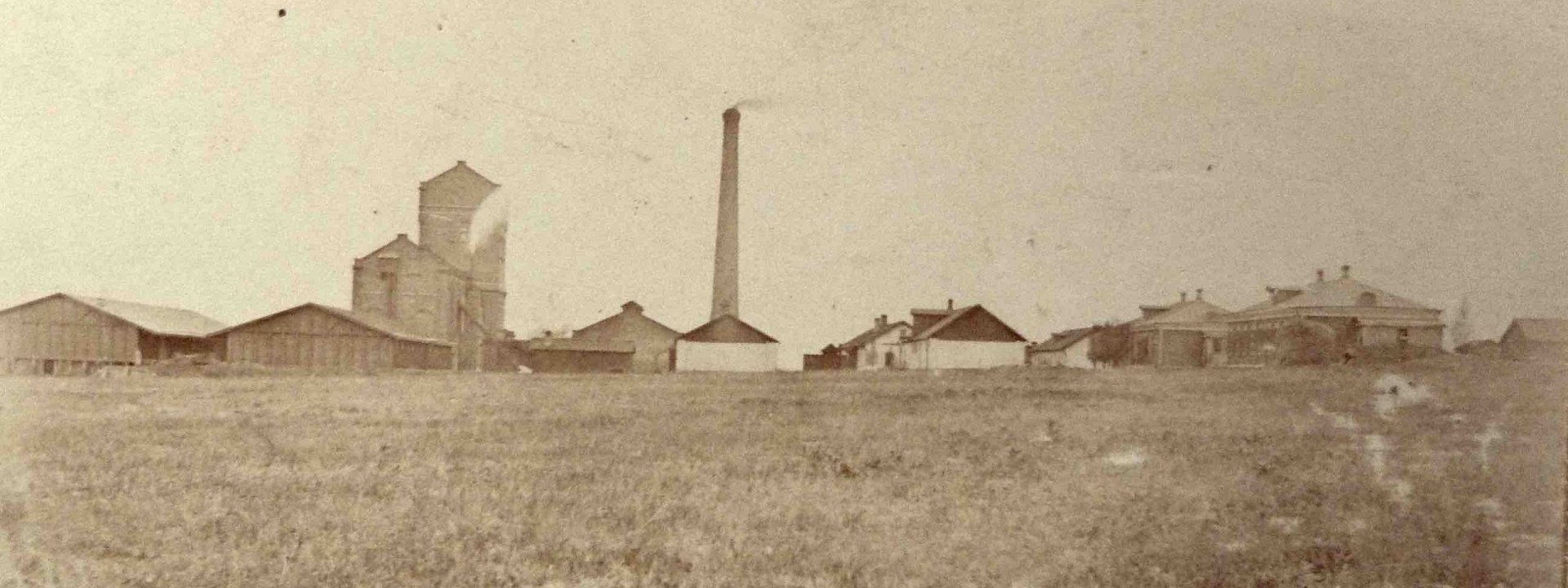

The industrial development of Donbas by the end of the 18th century influenced the rapid growth of the region's population, which eventually reached about 250,000 people. By the middle of the 19th century, its population reached 400 thousand. 62% of the population was Ukrainian and only 24% of the total population was Russian. Greek Tatars (Urums), Germans, Jews, and Tatars also make up a large part of the population. Moreover, there has never been a politically organized Russian minority in Ukraine overall. In the last census in 2001, 78% of the population defined themselves as Ukrainians and about 17% as ethnic Russians. Furthermore, the presence of Russians in the region should not be solely explained by the “proximity” of the countries. Russian settler colonialism goes back several centuries: it became widespread around the 16th century.

By the late 19th century, significant centers of heavy industry emerged in the Donets Basin. The industrial development of the region led to rapid economic growth in these areas, making them financially and socially appealing. Consequently, there was a notable increase in the influx of Russian migrants to these regions. For instance, towards the end of the 19th century, Russians accounted for 68% of the workforce in the heavy industry sector of the then-Katerynoslav province – today’s Dnipro. Additionally, another wave of resettlement happened after World War II, as Russian workers were sent to the Donbas region en masse to work in the coal mines.

The passport system in the USSR also accounts for the creation of more “Russians” in the region. Back in the USSR, your ethnicity would be stated in one’s passport, along with such a thing as “propyska” – a registered address. Such extensive details of one’s life presented in one’s documents, along with the existence of propyska, which follows the citizen from their birth to their death, stems from the Soviet structure of control and observation, as well as the intent to erase non-Russian identities. This is showcased by the peculiar time when these measures originated. Officially it was instituted during the Soviet period in 1932 when internal passports became obligatory for all citizens aged sixteen and older. This was the period of great manmade famine, Holodomor. Through recording and controlling the movement of populations the USSR authorities were able to artificially change the ethnic landscape of Eastern Ukraine, particularly in the areas where famine hit the most. Starved Ukrainian peasants were replaced by a new population of Russians (or people who simply had “Russian” as their ethnicity in their passport).

The fact that a person is a Russian speaker does not mean that they are ethnically Russian. It should go without saying, as no one would call a Canadian person ethnically English for speaking English, or intentionally call a Swiss person Italian because they come from Ticino.

The narratives propagated by Russian sources seek to undermine the legitimacy of the Ukrainian language and culture in Donbas, perpetuating the falsehood that Ukrainian-speaking populations are a minority in the country as a whole, and that the Russian language and culture are under threat. Russian propaganda often paints Donbas as historically disloyal to independent Ukraine, conveniently ignoring the rich heritage of Ukrainian language and cultural expression that has persisted in the region despite centuries of suppression and russification.

By highlighting selective historical events and manipulating census data, Russian propaganda attempts to bolster the notion of Donbas as a bastion of Russian identity, conveniently sidestepping the region's complex ethnic makeup and historical context – particularly that of Russian settler-colonialism. Historically, the East of Ukraine never yielded to Russian dictatorships. Throughout history, people resisted erasure of the Ukrainian language and culture, and the resilience of Ukrainians today was not built overnight, nor did it erupt only after 24 February 2022.

-b478bbe76fb80662b124ed8605d6b221.jpeg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)