- Category

- Latest news

“Be Brutal, No Mercy”: Russian Guards Granted Carte Blanche to Torture Ukrainian POWs

In the early days of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian prison administrations were instructed to torture captured Ukrainian soldiers, according to The Wall Street Journal, citing three former employees of Russia’s Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) on February 10.

At the onset of the invasion, Igor Potapenko , head of FSIN for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region, allegedly told an elite unit of the service—presumably FSIN’s special forces—to “be brutal and show no mercy to prisoners.”

Potapenko reportedly emphasized that violence against Ukrainian POWs would face no restrictions, and body cameras that could capture evidence of torture were removed from officers’ uniforms.

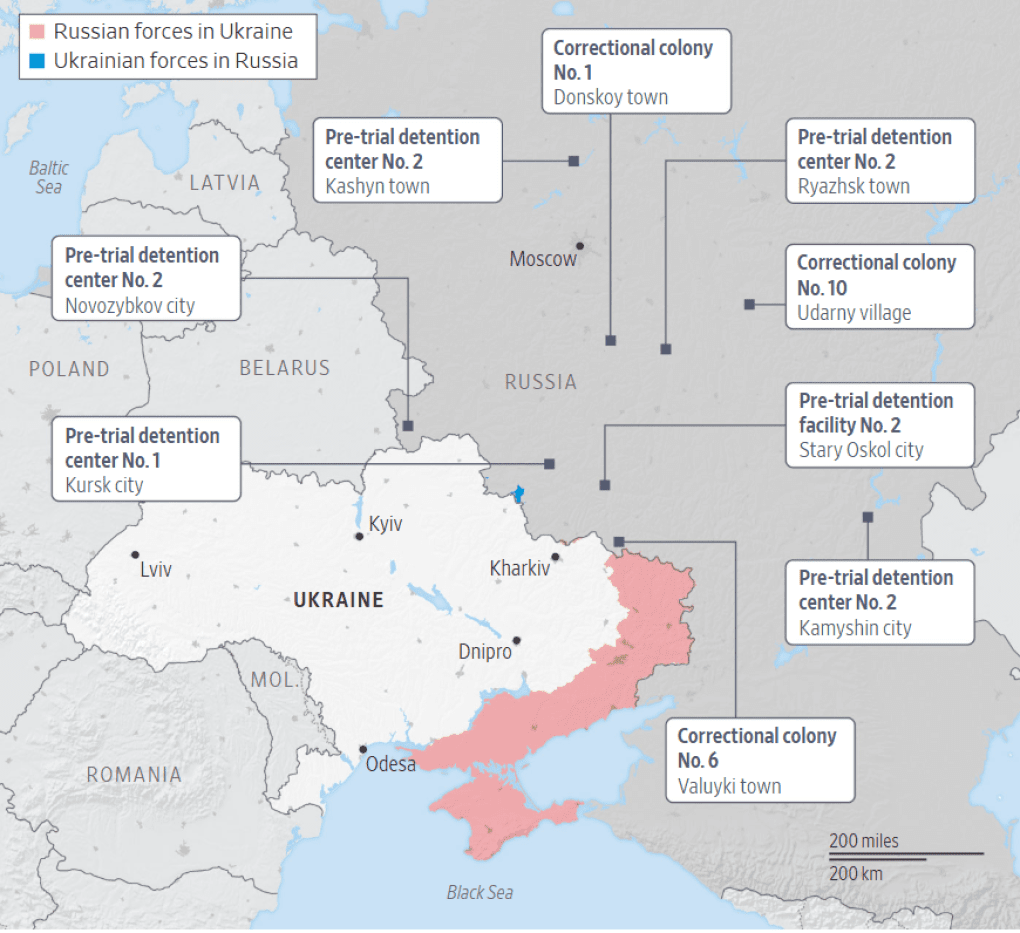

Additionally, FSIN staff assigned to oversee prisoners were subjected to regular rotation, ensuring that teams remained in the same prison for no more than a month. Similar instructions were distributed across Russia, including units from Buryatia, Moscow, Pskov, and other regions.

FSIN’s special units ended up overseeing local prison staff, with Potapenko’s March 2022 directives effectively granting them carte blanche for violence.

This marked the beginning of nearly three years of relentless and brutal torture of Ukrainian POWs in Russian prisons.

Guards used electric shocks on prisoners' genitals, beat them mercilessly, and withheld medical treatment to provoke conditions requiring amputations. The United Nations confirmed the systemic torture of Ukrainian POWs.

The WSJ’s investigation is based on testimony from three former Russian prison employees—two from FSIN special units and one prison medic—who entered a witness protection program after providing evidence to International Criminal Court investigators.

They claimed to have resigned from prison service before being ordered to torture Ukrainian POWs but maintained contact with colleagues still in the system. Their accounts are supported by documents, interviews with Ukrainian POWs, and testimony from an individual who helped facilitate their escape.

FSIN’s special units do not typically operate in specific prisons permanently; they function more like a “praetorian guard ,” deployed to suppress riots, conduct searches, and handle the most dangerous inmates.

When dealing with Ukrainian POWs, these special forces worked in coordination with local prison staff, closely overseeing their actions. One former officer admitted that after the invasion, mistreatment of Ukrainians escalated to a “new level,” with Russian personnel confident their superiors endorsed the violence.

Russian prison guards wore balaclavas during shifts, and monthly rotations ensured that prisoners could not identify their captors. Torture was used to break Ukrainians' will to resist, extract false confessions of “war crimes,” or obtain critical information, as prisoners were less able to resist after prolonged abuse.

According to former FSIN staff, electric shock devices were used so frequently—particularly in prison showers—that their batteries drained rapidly.

A medic from FSIN in the Voronezh region described how guards beat Ukrainian prisoners until rubber batons broke. When batons were no longer usable, guards resorted to using insulated pipes from boilers.

Prisoners were beaten in the same spots daily, preventing wounds from healing. This led to infections, blood poisoning, and muscle decay. One prisoner reportedly died from sepsis , the former medic claimed.

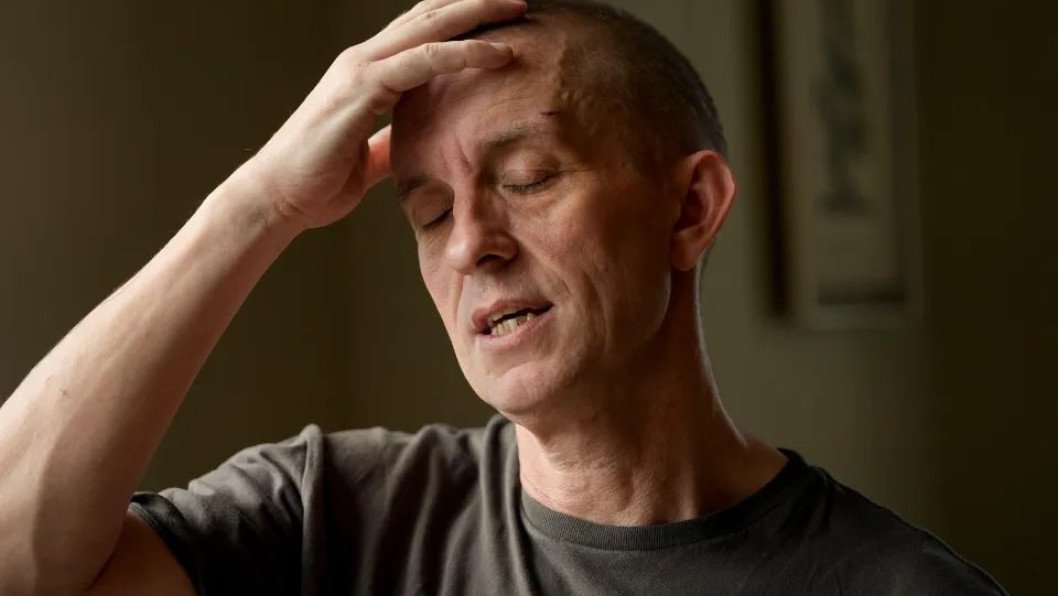

One of the first Ukrainian prisoners taken to Russia was Pavlo Afisov, captured in Mariupol in the early months of the invasion and released in October 2024. During his captivity, he was constantly transferred from one colony to another.

Afisov recounted that the most brutal beatings occurred during transfers to new prisons. Upon arrival in Tver, he was led into a medical office and ordered to undress. Guards repeatedly electroshocked him while he shaved his head and beard.

Afterward, they forced him to shout, “Glory to Russia, glory to the special forces!” and march naked across the room while singing the national anthems of Russia and the Soviet Union.

When Afisov said he didn’t know the lyrics, guards beat him again with batons and fists. After his release, Afisov was afraid to sleep for several days, fearing he would wake up back in a Russian prison.

Another Ukrainian POW, Andriy Yehorov, learned after his release that he had five fractured vertebrae.

“There I understood fear exists only for the future, you can be afraid of what happens in 10 or 15 minutes, you can be afraid of what might happen. But when it’s happening, you’re no longer afraid,” Yehorov said.

He recalled how, in Bryansk, Russian prison guards forced prisoners to sprint 100 meters down a corridor while holding mattresses over their heads. Guards lined the sides, striking prisoners in the ribs as they ran. At the corridor’s end, the prisoners were forced to do push-ups and squats, with guards beating them at every movement.

“They enjoyed it, laughing among themselves while we screamed in pain,” Yehorov recalled.

Earlier, reports emerged that Stephen James Hubbard, a 73-year-old former American teacher, endured brutal torture in a Russian prison after being captured by Russian forces in Izium, Kharkiv region, Ukraine.

-111f0e5095e02c02446ffed57bfb0ab1.jpeg)