- Category

- Anti-Fake

How Russia Revives Soviet-Era Punitive Psychiatry in Ukraine’s Occupied Territories

Refusing to bow to an occupier in Russia’s world labels you as “mentally ill.” Through forced diagnoses, drugging, and institutionalizing—even children—Russia’s modern occupation of Ukraine echoes a horrifying Soviet tactic: punitive psychiatry.

For over 50 years, the Soviets weaponized psychiatry as a tool of repression and control. The arbitrary diagnosis of “sluggish schizophrenia” targeted dissidents and ordinary people suspected of harboring anti-regime sentiments. Today, Russian occupants are reviving the practice of punitive psychiatry in Ukraine’s occupied territories in an attempt to shatter Ukrainian resistance and identity.

“Your disease is dissent”

Beginning in 1931, leading up to the Great Terror of 1936-38 Soviet psychiatrists diagnosed large numbers of ordinary people with a form of “mild schizophrenia”—later coined “sluggish schizophrenia”—a diagnosis unknown outside of the USSR and condemned by the World Psychiatric Association. Following Stalin’s death, the use of psychiatry as a political weapon remained consistent through the Khrushchev Thaw into the Perestroika era of the 1980s. During the late 80s, as Ukrainian symbolism such as the tryzub and signs reading “Live long free Ukraine” began to appear in public spaces, KGB surveillance of “nationalists” only intensified.

The Soviets claimed that “sluggish schizophrenia” was a “profound illness” yet were unable to characterize any clinical symptoms defining its diagnosis. Instead, the main diagnostic criteria were predicated on resisting communism since, in their view, only a mentally ill person could oppose communist ideology. Other key features included: possessing ideas about societal reform, holding religious convictions, and confronting authorities. People who exhibited none of the “symptoms” were also often arrested, diagnosed, and sentenced. Such was the case of Kharkiv-born Viktor Fainberg, who was told, “Your disease is dissent” by a St. Petersburg doctor during his institutionalization.

Once a person’s sanity was questioned, they had no right to be informed about the charges brought against them and it was at the court’s discretion whether the accused and their family were allowed to be present during the hearing—in many cases, even the hearing date was kept secret. Soviet secret police hunted for their victims as hospitals were repurposed into psychiatric prisons that warehoused thousands of political prisoners in an attempt to isolate, discredit, punish, and erase.

In 1971, the number of people recorded on the psychiatric register had nearly doubled to 3.7 million from 2.1 million in 1966. It was at this time that the 1971-1975 Five Year Plan resulted in the construction of over 114 new psychiatric institutions to house nearly 45,000 in-patient political prisoners. By 1989, over 10.9 million were registered by the Soviet apparatus, and psychiatric hospitals known as psikhushki became more feared than prison or exile by many.

“Do you like Soviet power better now?”

Between the 1960s and 1980s, the Soviets sought out those they deemed Ukrainian “nationalists” with particular force. In a political environment of total russification, Ukrainian speakers became immediate targets for “fomenting nationalistic sentiments”—people who continued to speak Ukrainian were diagnosed with acute psychosis. Standard “treatments” included beatings, sexual abuse, shock therapy, injection of turpentine oil as a “drug therapy,” the use of tranquilizers and sedatives, and even the forced consumption of live frogs.

In the 1970s, the majority of psychiatric prisoners were Ukrainians, a finding supported by survivor testimonials—former prisoner Semen Gluzman (a Ukrainian psychiatrist himself) shared that during his sentence he never met a single Belarusian, Uzbek, Tajik, or Kyrgyz despite the operation of the KGB in all of the Soviet republics. The true scale of Ukrainian repression will never be known as the files of “nationalists” were accessible to only a handful of approved officials.

Hospital staff took special pleasure in humiliating Ukrainian patients they considered nationalists, often beating them to death. Sadism appears to have been a selection criteria for Soviet psychiatrists and staff. Soviet psychiatrist Arkady Zhuravsky purposely injected turpentine into the bone, causing excruciating pain that worsened with every hour and resulted in spasms and other neurological symptoms. After the injection, he’d ask, “Do you like Soviet power better now?” Many died from injection overdoses. Those lucky enough to be released were forced to sign documents stating they would refrain from speaking Ukrainian and that they would work to benefit the state going forward; they were also forbidden from sharing where they had been during their disappearance.

Details about some of the “patients” interned at these institutions and their experiences emerged only much later. Leonid Plyushch, a Ukrainian mathematician and member of the human rights organization Ukrainian Helsinki Group, explained how the institution where he was detained had machine gunners perched at watch towers. It was common for the institutions to be near or even on the territory of prisons. Plyushch outlines the details of his arrest and detainment in the memoir, History's Carnival: A Dissident's Autobiography.

Dr. Olha Bertelsen, a Ukrainian professor of Global Security and Intelligence concluded that the so-called treatment was “designed to leave a permanent scar in the souls of oppositionists who were supposed to live for the rest of their lives with the memory of horror and fear which would substantiate psychiatrists’ claims about their insanity.”

The infamous Moscow Serbsky Institute where many of the victims were detained and tortured, continues to operate to this day under the new name of Serbsky State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. The patient files remain sealed.

“If you support Ukraine, you are mentally ill”

Today, Russian occupiers have resurrected Soviet-era punitive psychiatry in an attempt to, once again, break Ukrainian resistance.

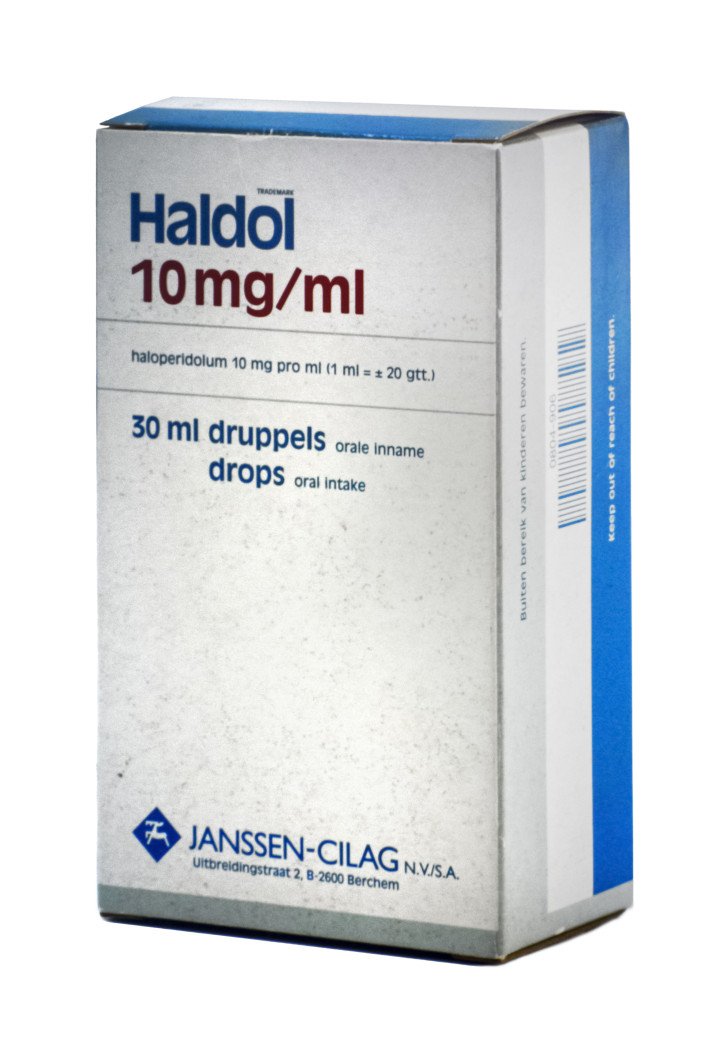

In 2023, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group reported on a Kharkiv woman known only as “Iryna” who was sentenced to ten months in two different psychiatric facilities in Russia for refusing Russian citizenship. During her imprisonment, she was forcibly medicated with haloperidol, an antipsychotic drug primarily used for the treatment of schizophrenia.

Surpassing the depravity of even their Soviet predecessors, modern-day occupiers target Ukrainian children. In occupied Mariupol, Russian forces have listed 263 Ukrainian youth on a register similar to those used in the Soviet era, with 48 deemed “radical” and sentenced to “treatment” in a psychiatric facility. Regarding the illegal arrest, Russian propaganda claimed that the youth had been enticed to commit “terrorist” activities by Ukraine.

In the Russian-occupied Luhansk region, Pavlo Lysianskyi, the director of the Institute for Strategic Studies and Security, stated that 31 minors had been sent to forced psychiatric detention this year alone. Echoing the 1971-1975 Five Year Plan, new psychiatric penal institutions are being erected in the occupied areas of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

In occupied Berdyansk, teenagers face punitive psychiatry for writing any social media commentary that the occupying forces can interpret as “pro-Ukrainian,” the deputy head of the Berdyansk district council, Viktor Dudukalov, told Freedom TV station. “It sounds so eerie and blasphemous that they have to recognize a person as mentally ill because they have a pro-Ukrainian position,” he said. “What year is it now? It’s like 1937 all over again.”

Lawyers from the human rights group Skhidna supported Dudukalov’s remarks, sharing with Radio Liberty that in occupied territories, “if you support Ukraine, you are mentally ill.” The group confirmed cases of abducted youth, saying their whereabouts are currently unknown; boarding schools in Berdyansk, Preslav, and Kalynivka are being converted into psychiatric detention centers.

The Mariupol, Luhansk, and Berdyansk cases were documented in 2024, but the torture has been ongoing for a decade in occupied Crimea. In 2016, Amnesty International reported on Ilmi Umerov, a Crimean Tatar activist, who had been sentenced to forced psychiatric confinement in response to his peaceful resistance to the Russian occupation of Crimea. The following year, the Crimean Human Rights Group publicized the case of Yunus Masharipov, also a Crimean Tatar activist, who the Russian Security Service (FSB) arrested in occupied Yalta in 2017 for allegedly manufacturing explosives and sentenced to a psychiatric facility indefinitely. Masharipov’s appeal was held behind closed doors and his request to be “deported” to Ukraine from occupied Crimea was also denied.

Human rights organization ZMINA highlighted that people with disabilities are also forcibly detained in psychiatric hospitals; Oleksandr Sizikov, a Crimean with total vision loss, was targeted for attending two demonstrations against the illegal detention of political prisoners. He was arrested on July 7, 2020. “Absence of proper conditions and personal assistance may cause serious violations of Sizikov’s rights,” said ZMINA. “In particular of the right to have his honor respected and his dignity recognized”—this didn’t stop the Russian occupiers from sentencing Sizikov to 17 years on May 17, 2023.

As of November, Crimea SOS, Ukraine’s NGO that supports internally displaced persons (IDPs) and advocates for Crimean rights, reported on at least 18 known Crimean political prisoners sent to psychiatric detention: Ernest Ibrahimov, Azamat Eyupov, Lenur Seydametov, Oleh Fedorov, Nariman Dzhelyal, Raiif Fevziyev, Oleksii Chyrnii, Arsen Dzhepparov, Nariman Memedeminov, Emir-Usein Kuku, Server Mustafayev, Remzi Bekirov, Enver Krosh, Seiityaha Abbozov, Aziz Akhtemov, Edem Bekirov, Rinat Aliyev, and Vilen Temerianov.

-8fda54010650befcec1e2c4d694c566b.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)