- Category

- Culture

Remembering the Talented Ukrainian Minds Killed by the Soviet Union and Now, Russia

The Soviet Union has historically persecuted Ukrainian cultural figures—in an attempt to erase Ukraine’s identity and stifle dissent. Today, Russia continues to do the same.

There are many great intellectuals that a Ukrainian person can think of when they hear the words “Executed Intelligentsia,” from Mykola Khvylovy to Alla Horska to Victoria Amelina. But a lot of these names remain unknown to those outside of Ukraine.

This obscurity is largely due to Russia's historical and ongoing efforts—both as the Soviet Union and in its current state—to suppress Ukrainian talent. This has manifested through several waves of persecution, from the "Executed Renaissance" to the silenced "Sixtiers," and now the wartime targeting of Ukrainian creatives. Russia's aim has been the systematic eradication of Ukrainian identity by eliminating its intellectual leaders.

Every period of Ukrainian cultural resurgence has been met with severe repression from Russia. Consequently, a significant number of Ukrainian intellectuals have perished in Stalin's prisons, have been assassinated by the KGB, or are currently being killed on the battlefield or in missile strikes by Russia.

“Executed Renaissance” of the 1920-30s

To appreciate the renaissance essence of early 20th-century Ukraine, it's crucial to grasp its historical backdrop: Ukrainians endured systematic oppression aimed at eradicating their ethnic identity for three centuries. The 1863 “Valuev Circular” was a covert directive issued by Pyotr Valuev, the Russian Empire's Minister of Internal Affairs, which severely restricted Ukrainian language publications.

Valuev's statement encapsulates the essence of this Russification effort: "The Ukrainian language never existed, does not exist, and shall never exist.".

During the 1920s and 1930s, Ukraine experienced a surge in national consciousness and a flowering of its arts and letters. This period was marked by a generation of extremely talented writers, artists, and scholars who sought to create a unique Ukrainian cultural identity that was separate from Russian or Soviet influence. This cultural renaissance produced a body of work that drew on Ukraine’s rich history, folklore, and contemporary experiences. Repressed writers in Ukraine like Mykola Khvylovy, Valerian Pidmohylnyy, and Mykhailo Semenko pushed Ukrainian literature in new directions, experimenting with form and content. Artists like Vasyl Sedlyar and theatre directors like Les Kurbas revolutionized visual and performing arts with new styles and techniques.

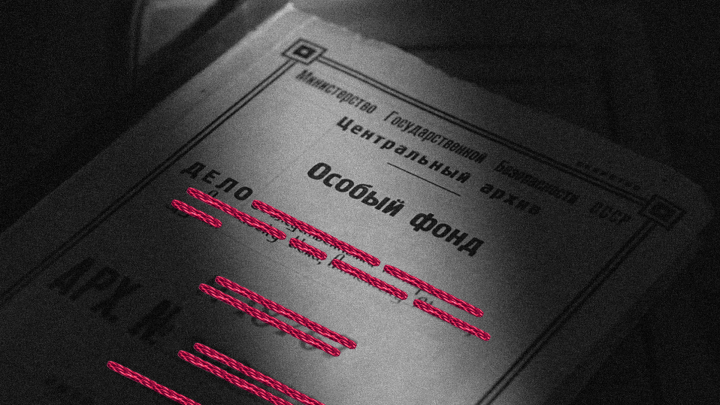

However, their efforts were brutally suppressed by Stalin's regime during the Great Purge, resulting in the imprisonment, exile, or execution of many of Ukraine's intelligentsia. From 1929 onwards, the Great Purge saw the systematic roundup of Ukrainian intellectuals.

The Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU) trial in 1930 was one of the most notorious show trials, where numerous repressed Ukrainian cultural figures were accused of nationalist activities and conspiring against the Soviet state. Many were executed or sent to labor camps, where they perished.

The specific targets of the SVU trial were the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox church, and the Ukrainian cooperative movement. These Ukrainian institutions were of the utmost importance to Ukrainian identity, which was seen as a threat to the Soviet government as they were beyond the regime’s control. Thus started the purge on prominent Ukrainian figures: the show trials were only a warning of what followed.

After the SVU trials, new criminal cases arose. The darkest period came in 1937 when numerous Ukrainian intellectuals, writers, artists, and scholars mentioned above were arrested as part of Stalin's massive effort to eliminate any potential threats to his power. These individuals were often accused of nationalist sentiments, espionage, or anti-Soviet activities, on fabricated charges. The crackdown was not limited to Ukraine but also affected many other regions within the Soviet Union. A total of 58 ethnic groups were murdered in the Sandarmokh.

Among the 1,111 prisoners brought to the forest from the Solovetsky camp of the USSR Gulag system in October 1937, there were 290 Ukrainians: above-mentioned theatre director Les Kurbas, playwright Mykola Kulish, neoclassical poet Mykola Zerov, former Minister of Education of the Ukrainian People's Republic Antin Krushelnytsky and his sons Ostap and Bohdan, historians and academics Matviy Yavorsky, Professor Volodymyr Chekhivsky, writers Valerian Pidmohylnyy, Pavlo Filipovych, Valerian Polishchuk, Myroslav Irchan, Marko Voroniy, Oleksa Slisarenko, Mykhailo Yalovy, scientists Mykola Pavlushkov, Vasyl Volkov, Petro Bovsunivskyi, Mykola Trokhymenko, and many more.

The executions were carried out from October 27 to November 4, 1937, deliberately scheduled to align with the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution. The events at Sandarmokh were meticulously hidden by Soviet officials, and the full extent of the tragedy only became known in July 1997 thanks to the efforts of Yuriy Dmitriyev. A researcher of the history of political censorship of USSR, a human rights activist, and the head of the Memorial Human Rights Centre of Karelia, he is currently serving a 15-year sentence in Russia.

This dark period was a severe blow to Ukrainian culture and intellectual life, with repercussions that lasted for decades. Exact data on the number of repressed Ukrainian intellectuals during the Stalinist repressions of the Executed Renaissance period are unknown.

However, it is possible to determine approximate numbers of repressed persons among writers: by the availability of their publications in the early and late 1930s. Thus, according to the assessment of the "Slovo" Association of Ukrainian Writers in Exile, 259 Ukrainian writers were published in 1930, and after 1938 - only 36 (13.9%). According to the organization, 192 of the 223 "disappeared" writers were repressed (shot or sent to camps with possible subsequent execution or death), 16—disappeared, and eight—committed suicide.

“Shistdesiatnyky” or the “Sixtiers”

The "Executed Renaissance" marked a dark period in Ukraine's history, paving the way for further cultural suppression, particularly during the "Sixtiers" or "Shistdesiatnyky" era. The new generation of artists, writers, and thinkers sought to revive national consciousness and break from the ideological constraints of the post-Stalin era in the 60s. At its core were young people inspired by Khrushchev’s “Thaw”. The thaw was a period of soft totalitarianism: there was relative freedom in the media, arts, and culture.

The “Sixtiers” engaged in a range of cultural pursuits, such as hosting underground literary gatherings and art showings, organising memorials for artists who had suffered repression, and staging theatrical productions. They made appeals to advocate for the preservation of Ukrainian cultural heritage. They were the generation born during or right after the Great Terror. The initial spokespersons of the Sixtiers movement in Ukraine were Lina Kostenko and Vasyl Symonenko. The former is known for her poetry, which has made significant contributions to Ukrainian literature, and the latter is known for his incisive journalistic poetry challenging Russification and the national subjugation of Ukraine.

Vasyl Stus is another name known to every Ukrainian. A poet, translator, literary critic, and journalist, Stus is remembered not only for his poignant and deeply introspective poetry but also for his tragic fate as a victim of Soviet repression of intellectuals. He became an outspoken critic of the Soviet government's policies, particularly those that oppressed the cultural and national identity of Ukraine. His refusal to renounce his views led to his arrest in 1972.

He was charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. Vasyl Stus' life came to a tragic end on September 4, 1985, when he died in a Soviet prison camp, the Perm-36 in the Ural Mountains. He had been on a hunger strike, protesting against the inhumane conditions and his wrongful imprisonment. Stus's death made him a symbol of the struggle for Ukrainian independence and free speech. Buried in an unmarked grave at the camp, his body would not be discovered and re-buried on Ukrainian land until 1989.

Some of the “Sixtiers” had more enigmatic deaths. Artist Alla Horska is known for her nonconformist art movement that sought to push back against the rigid constraints of socialist realism prescribed by Soviet authorities. Her activism was not limited to her art; she participated in protests and was outspoken against political repression, which made her a target for the authorities.

On November 28, 1970, Alla Horska traveled to see her in-laws near Kyiv but never returned. Her body was later discovered in the basement of her husband's father, Ivan Zaretsky, several days after her disappearance. She died from injuries inflicted by "blows from a blunt object with a confined impact zone," likely a hammer. Ivan Zaretsky's life also met a tragic end; his body was located on a railway track the following day. There has been no proper investigation of Horska’s death to date. The archival documents connected to the artist’s death have been lost or destroyed.

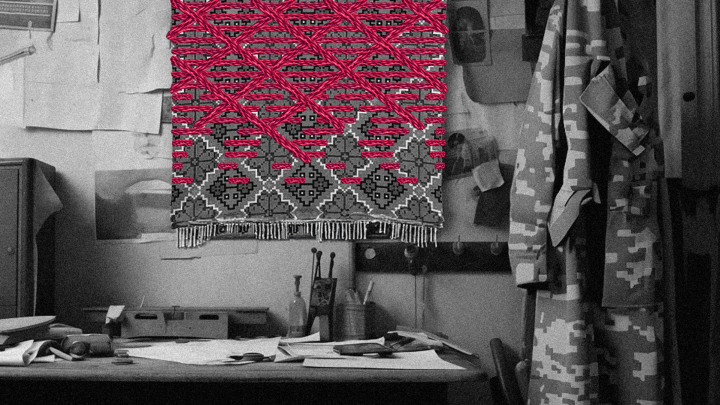

Some other prominent intellectuals include writers Ivan Drach, Valerii Shevchuk, Mykola Vingranovsky, Hryhir Tiutiunnyk, Yevhen Hutsalo; painter Viktor Zaretsky; textile and painting artist Lyubov Panchenko; literary critics Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstyuk; director Les Tanyuk; and film directors Sergei Parajanov and Yuri Ilyenko. Many faced severe repression, censorship, beatings, and imprisonment.

The plight of the Sixtiers serves as a continuation of the struggle for cultural survival and freedom of expression in Ukraine, echoing the earlier sacrifices of the Executed Renaissance.

Present day

Since the start of the Russian invasion in 2014 many Ukrainian artists had to pick up arms instead of pens and brushes. Some also fell victim to abductions, and some to bombs while living their civilian lives.

“The evening tea sits on the table.

A book on the sideboard.

Dear daddy, read me

Some fairytales of various colours.

About a baby elephant, and how

He watered flowers.

About the grain that was sown,

Suckled by the little sun.”

So opens “Daddy, Read!”, a children’s poem by the late Volodymyr Vakulenko. An author of children's books, he was abducted from his residence by Russian forces in the spring of 2022. Ukrainian officials later discovered his remains in a mass grave in the village of Kapytolivka on the outskirts of Izyum, where DNA testing confirmed his identity. Vakulenko was a vocal activist and was active during the Revolution of Dignity.

“Air-raid sirens across the country

It feels like everyone is brought out

For execution

But only one person gets targeted

Usually the one at the edge

This time not you; all clear”

Victoria Amelina, who dug up Vakulenko's notes that he hid from the Russians in his yard and initiated the publication of his diary, was also killed by Russia’s war. Amelina was a Ukrainian novelist and poet who became a war crimes investigator after the full-scale invasion. She was an avid promoter of Ukrainian culture, and in 2021, she founded a literature festival in New York, Donetsk oblast. She was killed in a Russian missile attack in Kramatorsk. Her poetry is widely available and translated into English.

“He took the cat that was like pastry

And said: Cat we need to go

War

Cold like ice

Came to us, like morning

Like life

Like Illness

The lesson called “Quiet Life” is over”

Maksym Kryvtsov, a poet, died while serving as a soldier in January 2024. His 2023 collection titled "Poems from the Loophole" predominantly includes poems that depict the harsh realities of the war. Maksym first went to war as a volunteer soldier in 2014. He was also an active participant in the Revolution of Dignity.

Yurii Kerpatenko, conductor of the Kherson Oblast Philharmonic was asked to hold a concert at the Philharmonic under Russian occupation. Kerpatenko repeatedly refused to cooperate with the Russian authorities until Russian soldiers shot him in his home.

Oleksandr Shapoval, soloist of Ukraine’s National Opera and Ballet Theatre, joined the Territorial Defence Forces of Ukraine on the second day of the full-scale invasion and later joined the Armed Forces. He died on the battlefield while defending Donetsk Oblast.

Liubov Panchenko, who was mentioned previously in this article, was an artist and fashion designer. A surviving representative of the Sixtiers, she lived in Bucha and faced Russian occupation at age 84. Panchenko passed from starvation and exhaustion she endured during the occupation. Her artworks are presented in the Sixtiers Museum in Kyiv.

This list is not exhausted; many Ukrainian artists are currently defending the country. The same goes for the list of those executed and repressed during the other two periods and in between them.

As we read the names of repressed and fallen intellectuals, it is vital to not only mourn the past but to nurture the future.

Yes, it is comparatively difficult to find Vasyl Stus’s poetry book in your local bookshop, unlike Leo Tolstoy’s “War and Peace.” But Ukraine continues to stand defiant, cultivating a cultural landscape rich with talent and determination—attracting more eyes and ears. The sacrifices of the past serve as a reminder of the cost of freedom and the importance of protecting the vibrant tapestry of Ukrainian identity. The “Executed Intelligentsia” are symbols of a nation's unbreakable spirit. Their legacies live on in the words we read and the art we admire.

-b478bbe76fb80662b124ed8605d6b221.jpeg)

-707273464d1ff31c2d79c472b81e1827.jpg)

-ef906d8c7daeee38b707ac8966246a92.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)