- Category

- Culture

Blind Minstrels—Kobzars—Once Guarded Ukraine’s History. They Still Do

Ukraine’s Kobzars were once the nation’s living memory—blind troubadours who sang of war, loss, and resilience. Nearly erased by Soviet purges, their tradition endures, echoing through time.

In the small concert hall at Kyiv’s National Museum of Literature, a group of men, most over 40, are tuning their instruments. The banduras—bulbous guitar-like instruments with a harp-like, hypnotic sound—are lying on couches while the sparse audience waits silently.

The concert is a rare gathering of today’s Kobzars—keepers of a tradition as bittersweet as a fable. For centuries, these non-seeing, itinerant musicians traveled from village to village, singing epic ballads and religious hymns —custodians of Ukraine’s oral history. They spread news, reinforced national identity, and were guided by young children—often orphans or disabled themselves. Relying on hospitality, the kobzar were revered as holy, in part due to their loss of sight.

One by one, the kobzars file onto the small, Wes Anderson-esque stage. Seated before yellow velvet curtains and surrounded by a flock of microphones, some play the bandura, others play the wheel lyre, winding the handle to produce sound—a marriage between the harpsichord and a bagpipe. Its tone, grave and full of tension, can feel alienating to the uninitiated.

Kobzar legacy defies Soviet erasure

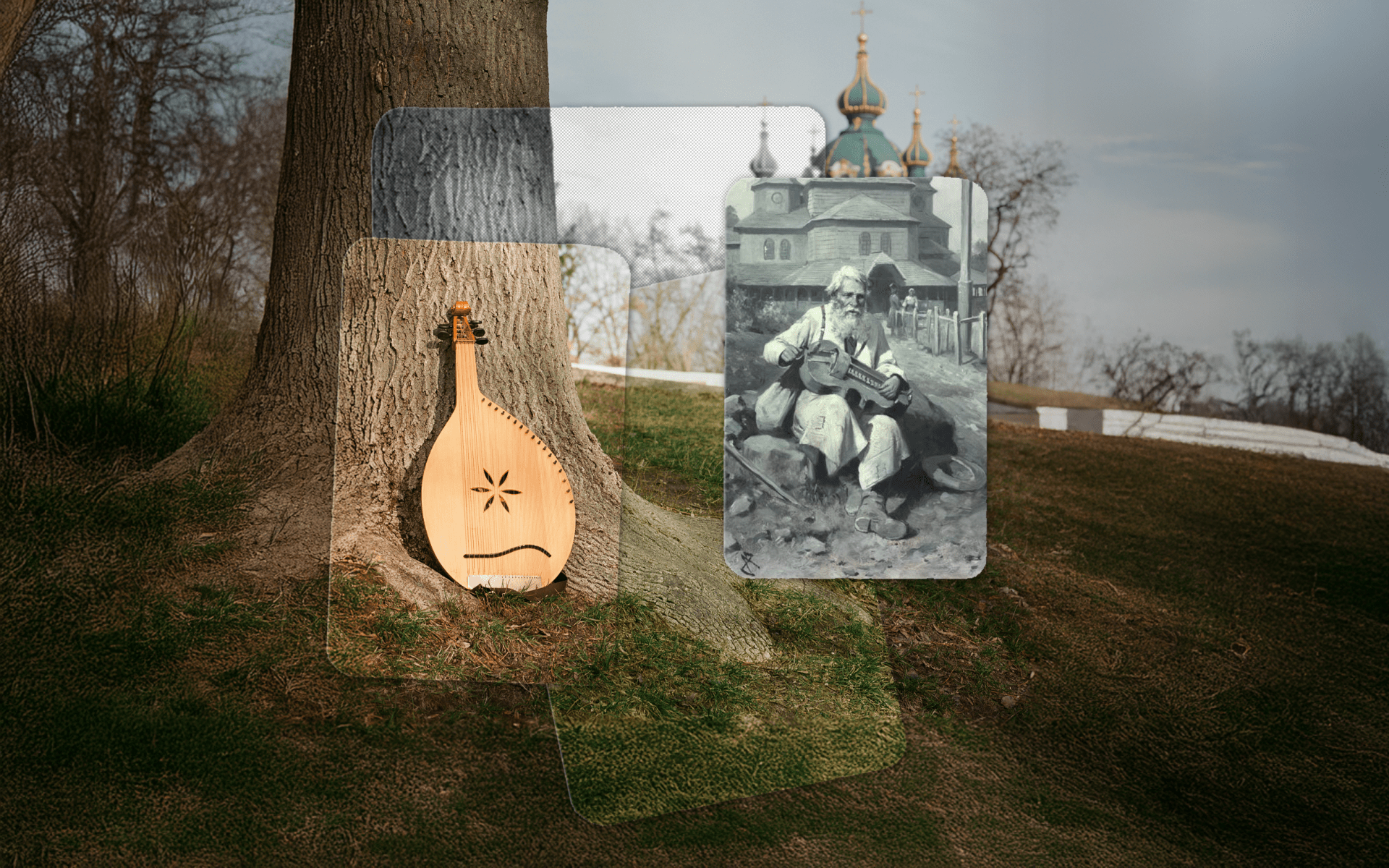

The kobzar community today is a fraction of what it once was, still reeling from the Soviet Union’s attempts to erase it. One of the people picking up the pieces is the luthier Andrii Paslavskyi, who, while studying Ukrainian folklore at university, became interested in the starosvitska bandura, a traditional instrument crafted from a single piece of wood, each one uniquely handmade.

Traditionally, the wood used to craft the instruments does not come from trees cut down for a specific purpose. “We don’t cut or buy trees,” Paslavskyi explains, the wood is “harvested” from trees that have fallen due to bad weather, pruning. Or more recently, “artillery fire which damages forests.” Russia’s full-scale invasion slowed everything down for him and he adds, an instrument takes 200 hours to make, and, “a minimum level of concentration and peace.”

One of the banduras he made during the war was crafted from willow found in the town of his teacher, Moshchun, 20 kilometers northwest of Kyiv. Three months later, Moshchun witnessed heavy fighting, and 90% of the houses were destroyed—the instruments miraculously survived.

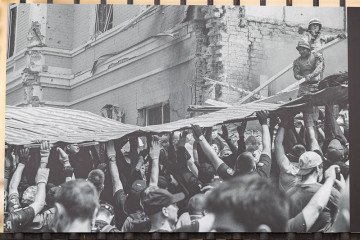

Although there is no access to the archives, held in Russia, some Ukrainian folk historians believe that in 1931, the Soviet regime invited Ukraine’s kobzars to a Congress of Folk Singers, only to have the NKVD execute them and their young guides in a forest near Kozacha Lopan, outside of Kharkiv. Their instruments were destroyed, and the tradition was replaced by state-approved ensembles like the Red Army Choir, which repackaged Ukrainian music into Soviet propaganda—a stark contrast to the solitary, blind kobzar.

Ukraine’s fight for independence is intricately entwined with the kobzar tradition. Its songs—Duma, epic ballads that translate to “meditation,” Psalmy, religious hymns and Satyry, Satirical duma—are preserved as historical artifacts. “Not a word added, not a word thrown out,” Paslavskyi says.

Keeping the Kobzar tradition alive

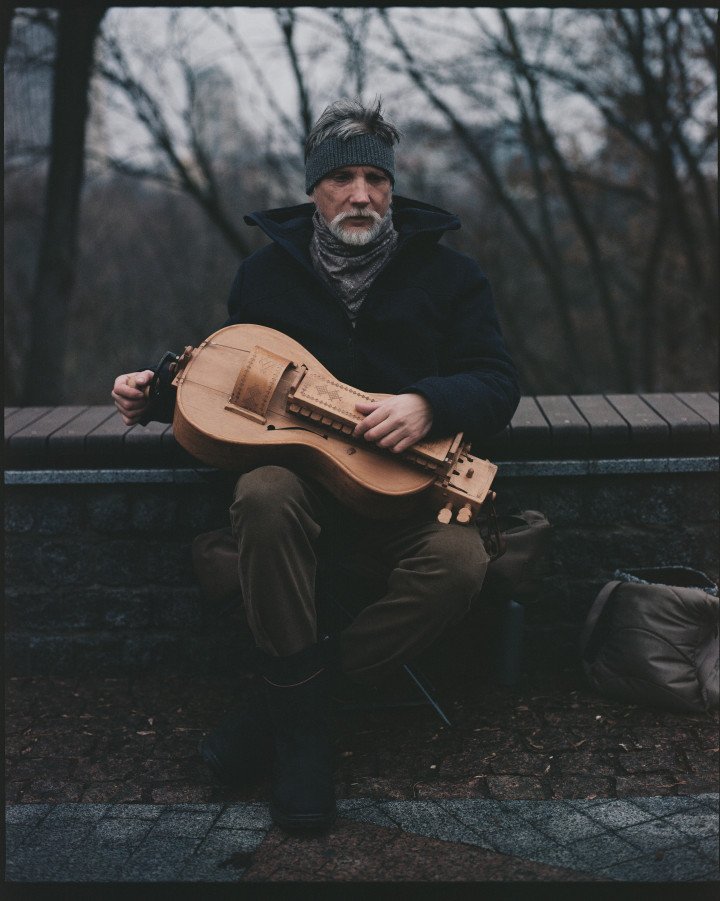

In Kyiv’s Peizazhna Alley Park, people stop and listen to Oleksandr Honcharenko, sitting, winding the handle of his wheel lyre. His grey hair and hood veiling luminous blue eyes. As Honcharenko plays, a cyclist stops mid-ride, one foot on the ground, listening. Others slow down, whispering among themselves. One of the most renowned duma’s begins like this:

“There is no truth in the world,

Truth is not to be found,

For dire Falsehood has started calling itself Truth.”

Commenting on truth is at the heart of the kobzar mission—observing its developments and disappearances, warning of history’s interminable grind. In order for the duma, psalmy, and other songs of the kobzar repertoire to resonate, the role demands more than knowledge. “To play well, you have to feel what you’re singing,” said Honcharenko, “It’s just one person and their instrument, nothing else. If you’re not sincere, it’s hard to do.”

In Ukraine’s agrarian society, visually impaired men, unable to work the fields, were apprenticed into kobzar guilds as children. They trained for years—first by listening, then by singing short passages, then entire epics. Only when their master deemed them ready would they undergo a final test: performing before a circle of seasoned kobzars. If they passed, they received their own bandura and the right to roam free.

Kobzars have always been pioneers, ahead of everyone else, reformers.

Andrii Paslavskyi

Ethnologist at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv.

Some kobzars, descended from Cossacks, turned to music after being blinded in battles against the Ottoman Empire. As the tradition evolved, they became the social media of their time, traveling to a specific ring of villages where the villagers would repay them with money and food. The kobzar spoke a secret language, enabling them to spot any con men, uninitiated kobzar who profited from the villagers' generosity.

The relationship between the musician and the audience remains deeply personal, especially since the war began. Paslavskyi has noticed a positive shift in how Ukrainians respond to the kobzar tradition explaining, “Kobzars have always been pioneers, ahead of everyone else, reformers.”

Ukraine’s folk revival

Today, Ukraine’s folk scene is thriving, with young musicians embracing tradition. Bands like Shchuka Ryba, which unexpectedly rose to fame after Russia’s full-scale invasion, perform in nightclubs while it’s not uncommon for twenty-somethings to take up folk singing. Yaroslav Yerin, a traditional folk fiddle player and member of the Kyiv Kobzar Guild, is among them. While preparing for university exams during the COVID-19 pandemic, he stumbled across a video online.

“I fell into some kind of trance,” he recalls. “Twenty minutes passed just like that.” The video featured Taras Kompanichenko, Ukraine’s renowned kobzar, performing a duma—a meditative epic ballad rooted in Cossack battles and oppression.

Yerin is jovial, his hair cut into a strict bob. Sitting on a chair cross-legged, in a room filled with children’s instruments and Ukrainian Christmas stars, he rests his violin on his lap. To him, dumas are Cossacks' direct memories. “Somebody 400 years ago was so shocked by what they saw that he made it into a song,” says Yerin. “It’s amazing, mind-blowing.”

Somebody 400 years ago was so shocked by what they saw that he made it into a song, it’s amazing, mind-blowing.

Yaroslav Yerin

One duma, Duma about Khvedir Bezridnyj recounts a mortally wounded Cossack’s final moments. He asks his squire to find his battalion and tell them he is dead.

“When I hear that song, I cannot help but think—it’s happening today,” says Yerin “I have friends who died on the front line. Everybody in Ukraine does, I guess. It’s just amazing how all of it was already in this“Folk memory.” Nothing has changed. Or at least, not much.”

Sofiia Andrushchenko, another young voice in Ukraine’s thriving folk scene, has been singing in an ensemble since she was four. Now 21, she performs with Shchuka Ryba as interest in Ukrainian folk music surged “tenfold.”

In April 2022, after the Russian retreat from the Kyiv region, Andrushchenko and other musicians traveled to Sloboda-Kukharska, a village that had been heavily bombed. An elderly couple, living in their car beside their ruined home, listened as the musicians began to sing. The woman stepped forward.

“Louder,” she said. “Sing louder.” As their voices carried through the ruined homes, more people gathered. The local residents led them from house to house.

On the way back, a volunteer drove Andrushchenko to a site strewn with mines and burned-out Russian vehicles. Among them lay the corpse of a soldier, decomposing in the grass. “I remembered a song,” says Sofiia. “About a Cossack who goes to war and dies. About how grass and flowers grow through his ribs. I looked at that corpse—the grass was growing through it. It had been lying there for a long time.”

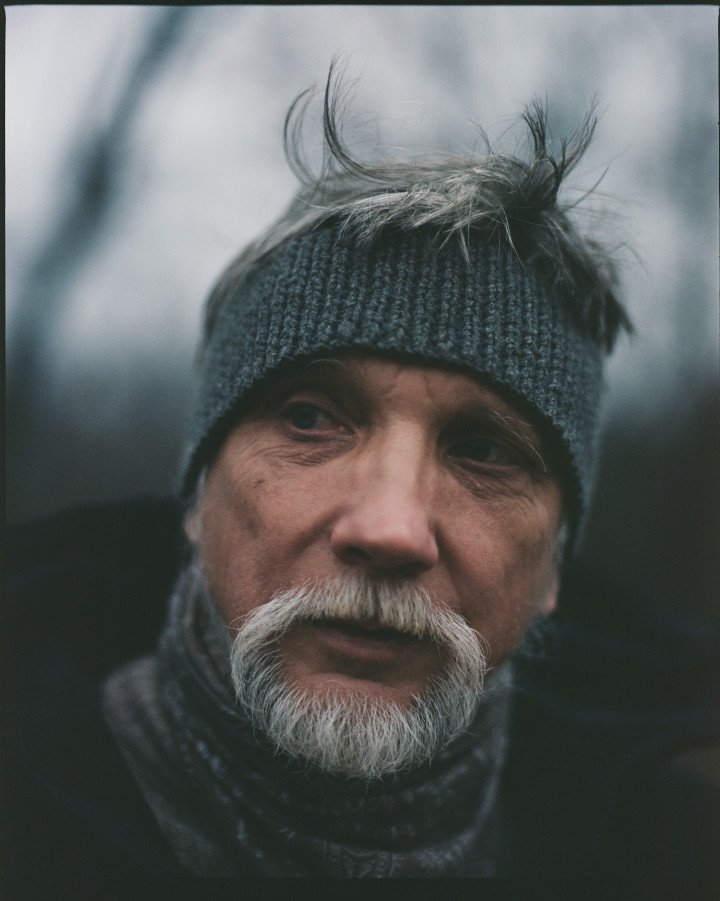

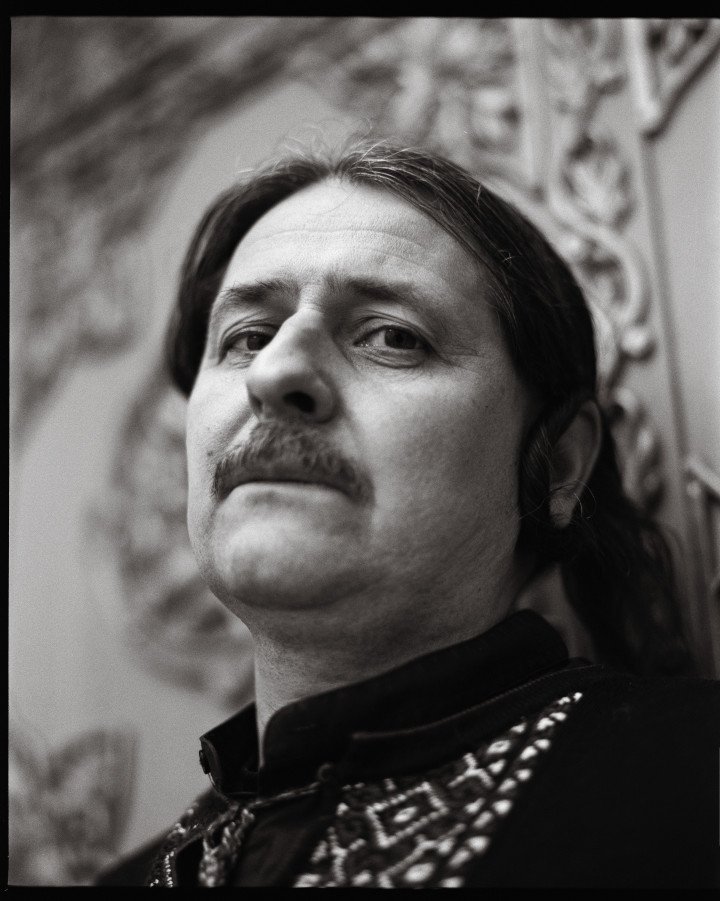

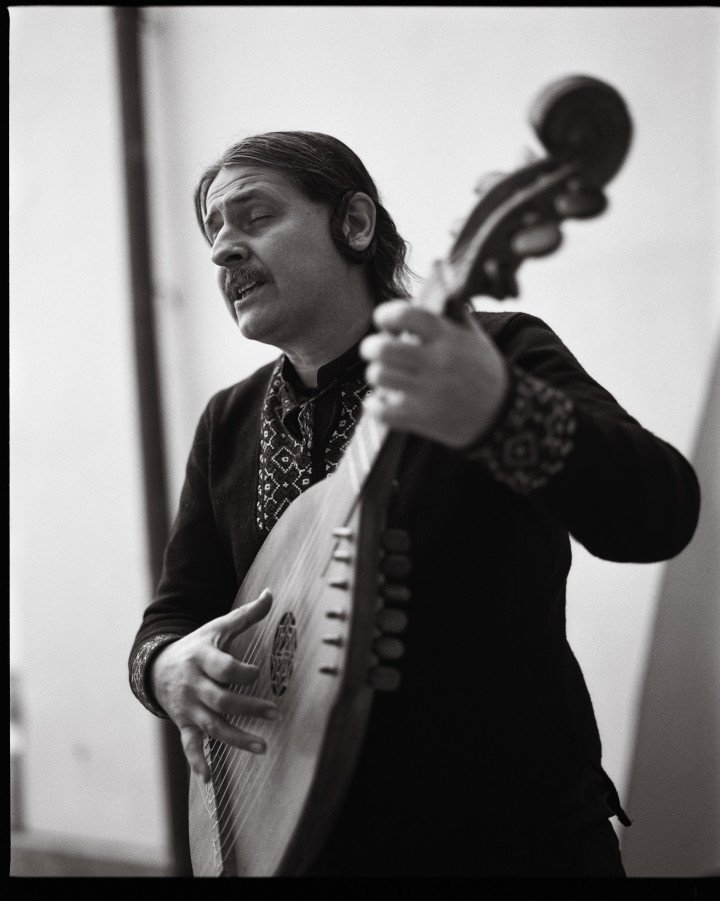

Taras Kompanichenko, a legacy before birth

Taras Kompanichenko was introduced to the kobzar tradition before he was born. While pregnant with him, his mother was moved to tears at a concert by Heorhiy Tkachenko—a kobzar who played a crucial role in preserving and reviving the authentic tradition. Nineteen years later, Tkachenko would become Kompanichenko’s mentor.

“It was a calling,” Kompanichenko says sheepishly—undoubtedly, he is an activist. He is also Ukraine’s most famous kobzar, but above all, he is an erudite and archivist who backs everything he says up with proof.

At a café across from Saint Michael’s Monastery, he unzips a pouch and takes out his tablet, flicking through what seems like hundreds of notes and archival screenshots. Noting that kobzars were once used to boost soldiers' morale in military units, he adds, “This is interesting because it was stated in 1919,” and taps the screen, pointing to the corresponding document.

Kompanichenko’s upbringing was deeply shaped by his grandfather, who spent 29 years in a Soviet prison camp in Arkhangelsk, 1,200 km north of Moscow, he says, “From my grandfather, who survived the Gulag, I learned that ‘Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished ’ was more than just a hymn. What I learned from my grandfather… I learned from him the words: ‘For 200 years, the Cossack has suffered under Moscow’s yoke.’”

His parents, determined to instill a strong sense of Ukrainian identity, made sure they spoke only Ukrainian at home. By age 14, Kompanichenko would draw tridents and copy old Ukrainian banknotes from his father’s collection, describing himself as a “conscious Ukrainian.”

In the final years of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev’s rule, Russification intensified, especially after Brezhnev’s 1970 decree, which forced all graduate theses to be written in Russian and approved in Moscow. Suddenly, Kompanichenko recalls, people considered those who spoke Ukrainian as “bumpkins,” while they still spoke Ukrainian at home, at school, and during breaks, his classmates would switch to Russian.

Once, he wanted to play a song from a Russian film for his grandmother on the bandura, and his grandmother said, “Playing Russian songs on a bandura?” Kompanichenko recalls, “It was a harsh lesson, but these were the rules. Because without such rules, we wouldn’t have survived.”

A tradition forced to adapt

The kobzar traditions, disrupted by the Soviet occupation until the 1980s, experienced a “pause,” as Paslavskyi puts it. While this break created “black holes,” Andrii believes it also allowed the tradition to evolve, ensuring kobzar’s relevance in contemporary Ukraine.

The revival, largely credited to Heorhiy Tkachenko—Kompanichenko’s mentor—was like piecing together a fragmented puzzle.

In the 1960s, Tkachenko returned to Kyiv and began teaching the starosvitska bandura to those interested in rediscovering the lost art. Driven by this initiative, a community primarily built of Kyiv intellectuals, came together to collect and piece together the scattered fragments of the kobzar craft.

Tkachenko’s bandura itself became a point of fascination, as most people had only ever encountered the Soviet reform version of the instrument and were deeply intrigued by the forgotten relic.

Paslavskyi, reflecting on this pause, argues that for Kobzardom to remain relevant and adapt, “It should be useful, if preserved, it will lose its relevance and will be extinguished. If something is not needed, it is discarded, like clothes that are not worn.”

Kompanichenko says he sometimes brings a Ukrainian Revolution era bandura to soldiers on the frontlines, crafted by a Cossack from the 3rd Iron Division and once owned by Kost Misievych—a bandurist himself, executed by the Nazis in 1943. Kompanichenko tells the soldiers they are holding a bandura that was once bought for the Rivne Ukrainian Gymnasium by Mykola Bahrynovskyi, the Minister of Labor in the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic, who donated it in 1930.

For Kompanichenko, this is when it all starts to make sense, “A bandura of the liberation struggle. Like a flag from the past. A relic. People begin to understand what this war is about. Even my comrades who once didn’t speak Ukrainian began speaking Ukrainian. Not because they were forced. But simply because… everything is falling into place.”

Songs for the fallen

Kompanichenko has always played at funerals, though since the full-scale invasion, this has been Kompanichenko’s main activity. After Russia’s full-scale invasion, Kompanichenko joined the 241st Territorial Defense Brigade in Kyiv. The 241st, the 112th, and the 114th brigades are his “home brigades,” where he has played on many occasions, at oath-taking ceremonies, and sometimes at the funerals of those same recruits.

Kompanichenko looks pensive and speaks pausing often, avoiding eye contact. “It terrifies me to think that these people were once at my concerts, at my lectures—and now, they’re gone. They gave their lives. For me, this is terrifying because… There are no strangers here. There are no other people’s children. This isn’t just words.”

We never thought these songs would be about us.

Father of a fallen Ukrainian soldier

Early in 2022, a father came to Taras after his son’s funeral and said, “We never thought these songs would be about us.” Kompanichenko never thought so either, as a response, Kompanichenko translated into song Taras Shevchenko’s 1845 poem “Testament” and sung it at soldiers' burials.

In the poem, Shevchenko asks to be buried on the Ukrainian steppe, where he can see the Dnipro River and the landscapes of his homeland. He calls for his people to rise and overthrow the oppressors, as 1845 was a pivotal year for Ukrainian independence and national consciousness, although much of Ukrainian lands, such as Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, and the Dnipro region, were governed by the Russian Tsarist Empire.

Kompanichenko recalls soldiers or their relatives reaching out to him, “My boyfriend wrote in his testament that he wants you to sing at his funeral.” Recently, he received a message from a fellow musician: “Taras, I’m at the front right now. That time, when you sang, it really hit me. Will you bury me?”

Ukrainian Dolya—a culture of agency

After his concert, Kompanichenko gathers with friends at a restaurant near the Kyiv fire station. The room hums with conversation, the air thick with laughter and the clinking of glasses.

We, Ukrainians—ours is a culture of voluntarism. We believe that things can be changed.

Taras Kompanichenko

A toast is called for, and Kompanichenko, holding up his wine glass, speaks:

“[The Russians] have tried to push something else onto us, this culture of fatalism. We, Ukrainians—ours is a culture of voluntarism. We believe that things can be changed—Ukrainian Dolya. You don’t have to believe in the Tsar. We are not fatalists. Ukrainians are voluntaristic, we rely on personal will as something that can change history, can change the course of your own life. And they—they are fatalists.”

In much of Europe, ancient Greek thought shaped the idea of fate as inevitable. From Oedipus to Cassandra, those who resist destiny only fulfill it. But Ukraine’s view of Dolya—its concept of fate—stands apart.

Olesia Naumovska, Head of the Department of Folklore Studies at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, quotes a Ukrainian proverb, “Don’t sit idly by, you forge your own fate,” confirming Ukraine’s unique almost unilateral understanding of destiny.

“Ukrainian people don’t have this regard to fate being predestined,” she says. Historians and scientists alike have written about this unique outlook—Dolya as an active force, shaped by human will.

The kobzar spirit embodies this same belief in agency. During times of profound upheaval, it reshapes cultural perspectives and proves that continuity isn’t always essential. Much like Dolya, the kobzars have reinvented themselves, sidestepping irrelevance.

As Paslavskyi put it, “Kobzars have always been pioneers, ahead of everyone else, reformers.”

Special thanks is extended to Oleksandr Rudovskyi, Yaroslav Yerin, Anna Diianchuk and the entire Kobzar community of Ukraine.

Cover Image: Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz “Lirnyk” 1898, Public Domain.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)