- Category

- Culture

The Artists Who Could Have Left Kharkiv—But Didn’t

In Kharkiv, a city battered by relentless Russian attacks, artists, curators, and performers refuse to leave their home. They won’t let the war silence them. Their studios double as bomb shelters, their exhibitions continue even amid blackouts, and their theaters adapt to missile alerts.

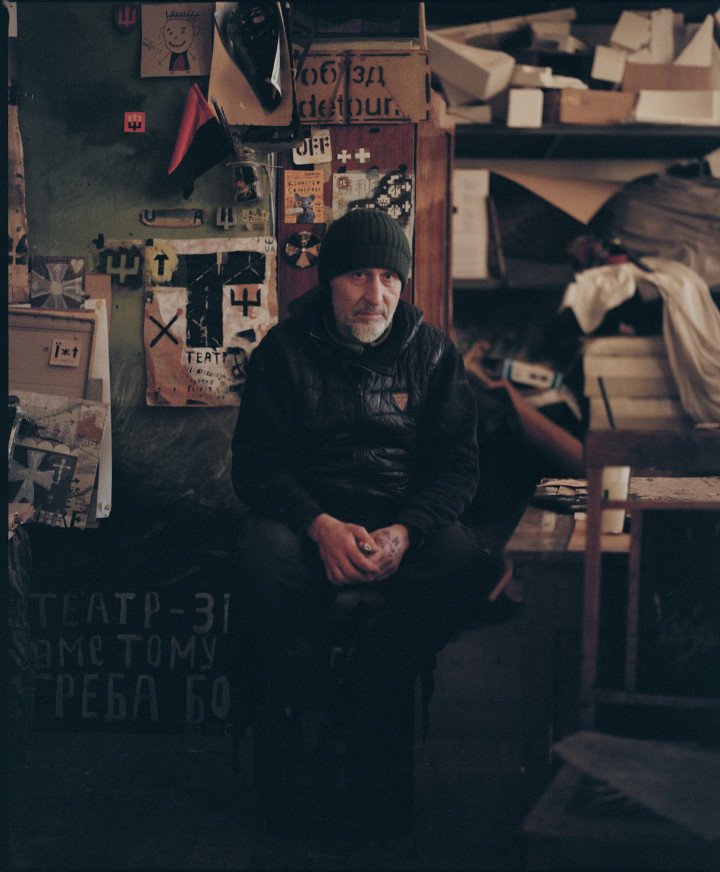

"I’m staying here because there’s no other place to go,” says Ukrainian artist Pavlo Makov. “This is my studio. This is the place where I live.”

For Makov, staying in Italy after representing Ukraine at the 2022 Venice Biennale was a real option. He had a place to live, financial stability, and a workspace, yet none of it mattered.

“I realized I had nothing else to do there. I was losing the sense of my existence,” he says. Returning to Kharkiv—a city pounded daily by Russian aerial attacks—was as if coming back to his senses. “I felt that people here needed my work.”

And they did. His 2023 exhibition at Kharkiv’s cultural and educational center of contemporary art, YermilovCentre, drew unprecedented crowds.

“A friend joked, ‘It’s like a rave party’—so many young people, old people, different generations,” said Makov. “It wasn’t just about art. People needed a sense that life was going on, even in wartime.”

The center’s director, Nataliia Ivanova, was thrilled to see Makov working alongside them in their beloved city. “I can go to his workshop, hug him, say ‘hello, Pashenka.’ It’s surreal.”

Bomb shelters with a canvas

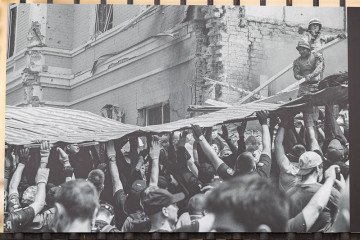

Art spaces in Kharkiv have become bomb shelters.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Aza Nizi Maza—a creative art studio for children and adults—was just that: a place for creativity. Now, it is also a refuge. As families fled, the studio transformed, housing not only artists but entire families.

The YermilovCentre faced a similar reality. When the contemporary art space opened an exhibition on February 22, 2022, no one knew that just two days later, everything would change.

“We never thought of our space as a bomb shelter,” Ivanova says. But when war broke out, fifty people—artists, their families, their children—ended up living there. “We stayed for ten days before deciding what to do next.”

Makov was among them. Even in those early days, he was preparing for Venice. “He gave an artist talk while we were sheltering,” Ivanova remembers. “People told him, ‘We don’t think you’re going to go.’”

But the war didn’t stop art. It thrived despite it.

“A full-scale war has been going on for three years, and we haven’t canceled a single event,” Ivanova says. When a March 2023 exhibition coincided with a night of Russia’s heavy bombardment of the city—no heat, no connection, no transport—the team improvised.

“We posted: ‘Everyone, come with lights.’ We connected a generator, ran extension cords, threw up some lamps—and opened the exhibition.”

But not every creative space can become a bomb shelter.

“In our theater, we can’t perform in our usual space—it’s not safe, and we don’t have bomb shelter status,” says Nina Kyzhna, director of Kharkiv’s Nafta Theater.

During rehearsals, they rely on Telegram news channels tracking Russian missile launches. “I’m probably the most anxious person in our team,” she says. “I’m always the one saying, ‘Guys, there’s a missile flying, get between the walls.’”

You don’t get used to it. Every explosion still makes me shake. The adrenaline might mask it for a moment, but the fear never goes away

Nina Kyzhna

Nafta Theater director

War speaks its own language

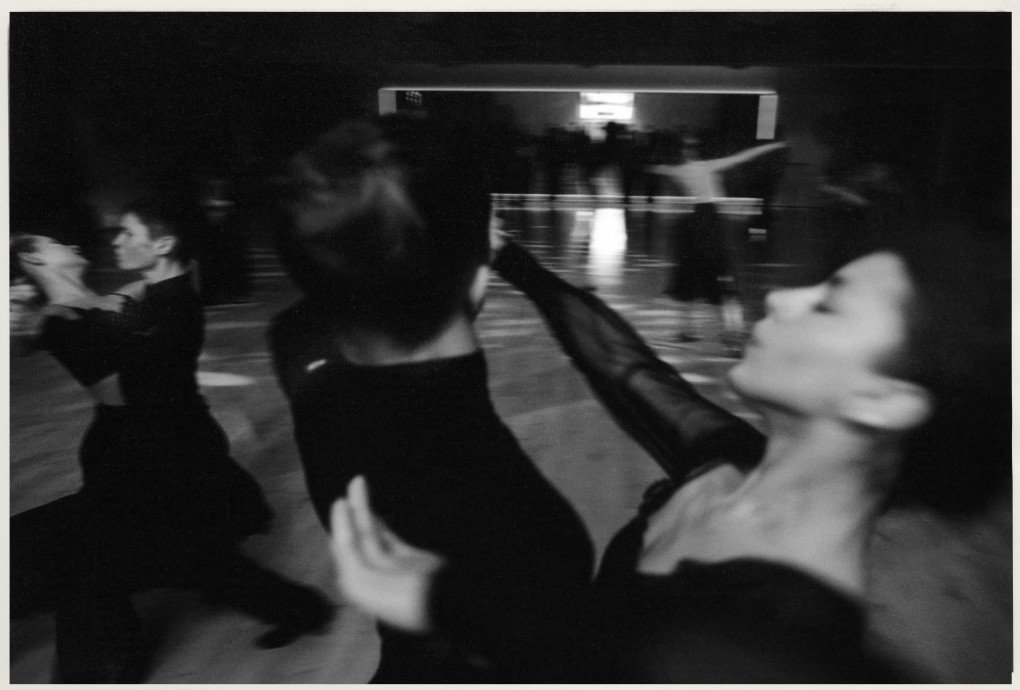

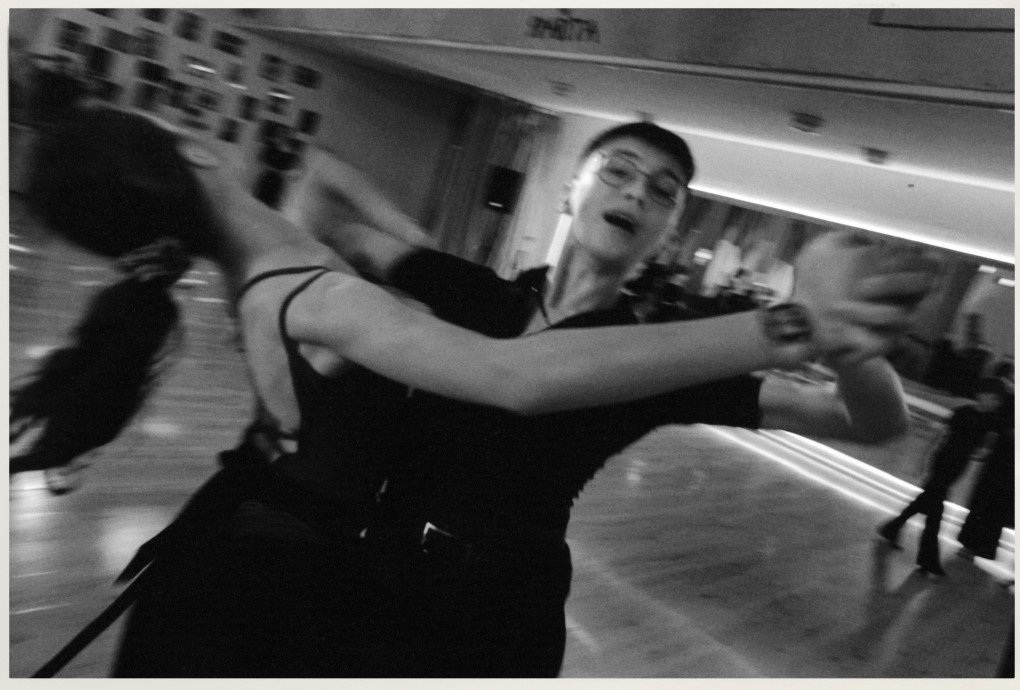

War has changed theater audiences.

“At one point, we were the only theater still operating in Kharkiv, apart from the puppet theater,” Kyzhna says. “Officially, performances were prohibited, yet shopping malls and cinemas remained open. We saw an influx of new viewers from all walks of life.”

For many, theater offers an illusion of normalcy. “People come to feel safe, even if only for an hour,” Kyzhna says. “But we also need theater to be a reflection of what is happening to us. That’s why we focus on documentary and post-documentary work, mixing real stories with fiction to help audiences process emotions.”

Theater has fulfilled a deep need—for people to be together, to share physical space, to feel that survival is possible together. “When air attacks happen, it’s always easier to be with someone than to be alone—especially when the bombardments are heavy.”

And one thing never changes: people cry.

“I’m glad they do,” Kyzhna says. “I see more men allowing themselves to cry. In our culture, that was always taboo. But war has changed everything. We’ve all become more mature. More realistic.”

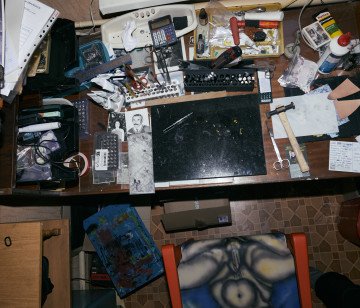

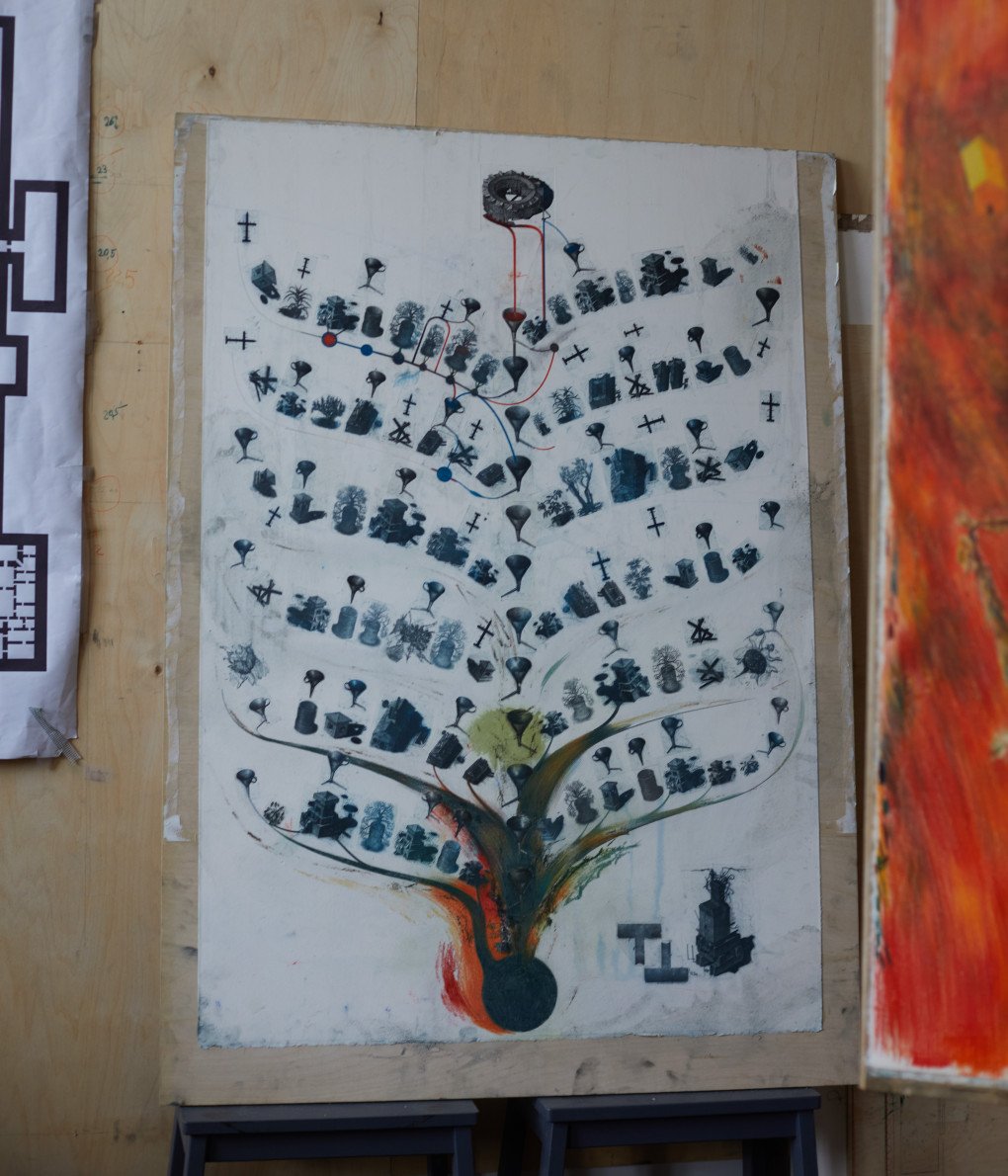

For Makov, war altered his artistic language. In Italy, his work was directly about war—he even depicted explosions.

“When I returned to Kharkiv, I realized that the closer you are to war, the less you can speak about it with the language of war,” he says.

Now, even if you make an exhibition about white and pink fluffy rabbits, it will still be an exhibition about the war.

Makov’s fellow artist from Kyiv

At the 2023 Personnel exhibition at YermilovCentre—held to mark a year of Russia’s full-scale invasion—Ivanova noticed something unusual during a curatorial tour.

“When I offered explanations, people said, ‘We understood everything,’” she says. “Because they had lived it. The shared experience made contemporary art universally understandable.”

Makov recalls the book The Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey by a US philosopher Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, who visited his studio a few times. “People respond to music without needing an explanation. You don’t ask ‘What does this music mean?’ You just feel it. The sound, the rhyme catches you. Meaning comes later.”

Reshaping Ukraine’s cultural scene

“We really lack our actors—some are abroad, some in safer regions,” says Kyzhna. “So we adapted. We created mono-performances requiring only one actor. This is how we survive.”

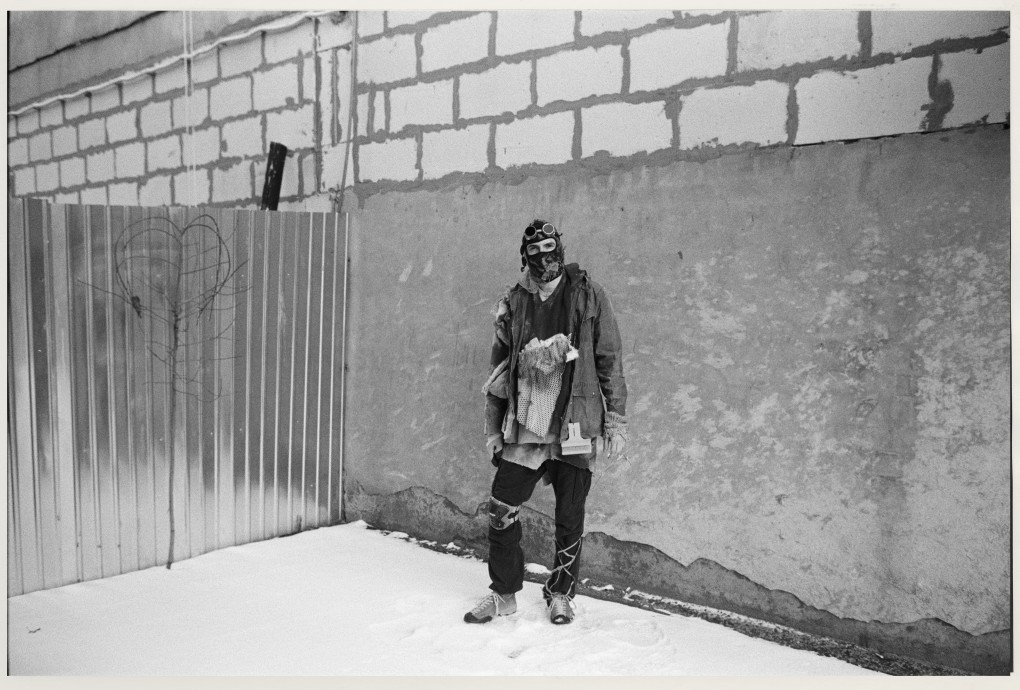

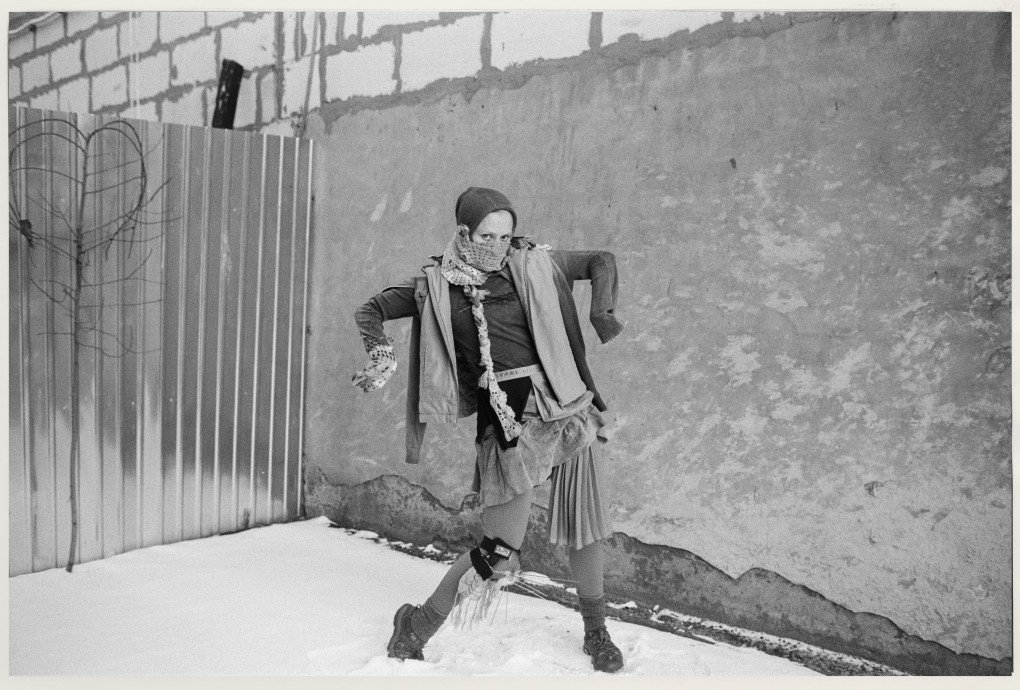

People changed in many art spaces. As the initial shock from Russian invasion receded, Aza Nizi Maza art studio slowly returned to its original purpose—not with the same children as before, but with those who had stayed or returned.

“Children have changed so much,” says the founder, Mykola Kolomyets. “The war disrupted everything. It’s impossible to say exactly how trauma has shaped them, but we had to reshape the space itself to meet their new emotional and psychological needs.”

Their latest project reflects the collision of past and present. Holocaust Memorial Center Babyn Yar commissioned them to paint a multi-storey house in Kyiv.

“They built a model of it here,” he explains. “We’re painting the walls in the studio before they’re sent to Kyiv.” The work is relentless, “just up to the neck,” says Kolomyets, meaning that there’s more to do than time allows.

The team built a full-scale replica of the house in their workshop, allowing them to refine the artwork before transferring it to Kyiv. The effort is immense. The lead artist admits to sleeping just four hours in two days to keep pace.

Yet, even amid war, they are documenting joy. “We’re making a book about all the writers from Kharkiv,” Kolomyets says. “From Skovoroda to those still here, writing in Kharkiv. A book about happiness.”

When Russia’s full-scale invasion began, children’s lives were upended overnight. The art studio became an anchor, offering a space to process fear and loss. Many early projects were massive collective efforts—murals in subway stations, museums, and public spaces. The work was not just about art but about survival, a way to reconstruct a sense of belonging.

Reclaiming identity through resistance

“Kharkiv has a complex, multilayered identity because of its proximity to the Russian border,” says Kyzhna. “For centuries, it was heavily Russified. Now, we have this complex trauma of Russification.”

Ukraine was long fed an artificial version of itself—staged folk dances, sanitized songs, “like a flat plastic picture.” But real identity is deeper. “We refuse to build our cultural identity around Russian imperial figures anymore,” she says.

For Kyzhna, theater is a “litmus paper,” a place to challenge taboos and political narratives. “If different perspectives can coexist on stage, it means we are fostering a society that values free expression and critical thought. After this war, our theater won’t just survive—it will transform.”

The fight for identity extends beyond the stage. “Putin spreads propaganda claiming Odesa is a Russian city, that Ukraine doesn’t exist. But we know better,” Ivanova says. “I have an embroidery passed down from my great-grandmother. It has traditional Ukrainian ornaments. We are from Sumy. How can anyone say this is not Ukraine?”

Makov agrees, pointing out Russia’s long-standing cultural manipulation. “For 300 years, Russia carefully built its image abroad, promoting its writers, composers, and artists. That’s why Europe struggled to accept the reality of Russian barbarism—they saw Pushkin and Tolstoy, not the real Russia.”

And yet, despite the devastation, Ukraine’s artists, curators, and performers continue. “Culture is a country’s open eyes,” says Makov. “Without it, a nation is faceless. Americans, for example, aren’t defined by their politicians—they are defined by their literature, their museums, their music.”

“Ukraine is a modern project,” he says, highlighting the need to create something new, something that makes people care about what the nation is doing. “We can’t build our identity just by looking backward.”

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)