- Category

- Culture

Ukraine’s ‘The Witch of Konotop’ Theater Play Goes Abroad to Enchant Europe

From the much-anticipated release of Wicked to Marvel’s hit Agatha All Along, witches have dominated the spotlight this autumn. Ukraine, too, is embracing this wave—not in cinemas but on stage—with the theatrical phenomenon The Witch of Konotop. While the US has its Salem, Ukraine has its Konotop.

At Kyiv’s historic Ivan Franko Theater, the lines for tickets to The Witch of Konotop have been a spectacle in themselves, with fans waiting hours to secure a seat. Tickets for the upcoming European tour? Better hurry up. What began as a local adaptation of a 19th-century Ukrainian classic has turned into a cultural phenomenon, captivating younger audiences who have made it a viral sensation with millions of views online.

What is The Witch of Konotop about?

This darkly comedic musical is based on Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko’s story, set in Konotop, Sumy region—a place with the same northeastern vibe as Salem and its own history of witch trials. Early in Russia’s full-scale war, the town entered modern folklore when a local woman confronted Russian soldiers, declaring, "You're in Konotop. Every second woman here is a witch," and following it with a threat of impotence.

The Russian threat looms large in The Witch of Konotop, even in its 1600s setting. Mykyta Zabryokha, a heartbroken Cossack leader of Konotop, reels from rejection by the beautiful Olena. Meanwhile, Tsarist Russia threatens the land now known as Ukraine, prompting an order from the Chernihiv Regiment for Zabryokha to rally his hundred-strong unit for a campaign. The play’s reality mirrors Ukraine’s present day, with Russia launching aerial attacks on modern Konotop and posing an ever-looming military threat.

Instead of preparing for war, Zabryokha, advised by his self-serving clerk, embarks on a witch hunt, blaming a prolonged drought on supernatural forces. In Konotop, the “witches” are not burnt on a pike. Women suspected of witchcraft are ruthlessly drowned to test their guilt: if they float, they are deemed witches.

Behind the scenes: Creating The Witch of Konotop

We talked to the director, Ivan Uryvskyi, who had long wanted to create something like The Witch of Konotop, but the timing never felt right—until now. After the first year of Russia’s full-scale war, he was ready to tackle it.

“I felt compelled to create something rooted in Ukrainian classics, blending folk traditions with irony,” he explained. “The beauty of theater is to be filtered through the audience’s experiences. I strive to create plays that offer layers of meaning, allowing each viewer to find their own story. Some will see comedy, others tragedy. While the ending of The Witch of Konotop is tragic, the playful delivery may lead the audience to initially interpret it differently.”

Russia’s brutal war has upended countless Ukrainian lives, leaving behind a trail of trauma and displacement. Yet, theater endures as a powerful cultural lifeline, drawing in even the youngest generation. No matter the story unfolding on stage, both the audience and performers bear the weight of this shared awareness: they are living in a country ravaged by war.

“The Witch of Konotop carries a sense of catastrophe,” says Uryvskyi. “It speaks of droughts, fires, and people preparing for the end of the world. War changes everything, including the way we approach these works. The theme of catastrophe is directly embedded in the story, and while it remains, I chose to express it differently. I approached it in a lighter, less forceful way, through an ironic undertone in the performance.”

The team behind the play wanted to convey a story that resonates deeply with many today, all while remaining mindful that here, in the theatre, the people may seek solace. Their daily lives are filled with anxieties like the next Russian missile attack, power outages, and news from the loved ones on the frontlines.

“I wanted it to feel—not my favorite word, but, alas,—‘comfortable’ for the audience, in terms of fostering dialogue,” says Uryvskyi. “I wanted to guide the audience down a different path—a brighter corridor—though dark forces still lurk in the corners. The play emerged from a shared state of mind between me, the actors, and the team.”

A visual and viral success

We asked Uryvskyi what contributed to the play's remarkable success. “Sometimes, a play just ‘clicks’ with people,” he smiled, shrugging. “No special effort was made to promote The Witch of Konotop. There was no advertising budget; it premiered alongside other productions.”

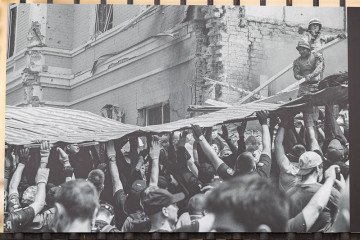

Visually, the play is nothing short of stunning, despite its simple execution, born from the necessity of working within a tight budget. But as the saying goes—there’s creativity in limitation. The play thrives on a stark contrast of black and white, with minimal decoration, which only adds to its charm—and its viral appeal online. It incorporates Ukrainian motifs, folk theater aesthetics, and even subtle hints of a musical.

“While the play may seem simple on the surface, it contains hidden meanings and ‘Easter eggs’ that not everyone may notice,” says the director. The witches are covered in white paint, seemingly “plastered” into the wall, as if a part of the environment itself. The characters, dressed in their black garments, immediately capture your attention against a backdrop of white, with the occasional black—or sometimes glowing—cross making an entrance. This striking stylistic choice makes it easy to recognize the play whenever a clip surfaces online. With over 30 million views on TikTok alone, it's clear that its online recognition is hard to miss.

Sometimes, there’s this rare connection, like a love affair between the audience and the play. It’s something you simply can’t explain.

Ivan Uryvskyi

Uryvskyi notes that every production teaches. “With The Witch of Konotop, I’ve been moved by its ability to raise big funds for Ukraine’s military through charity performances and auctions.” The success of these charitable events has been immense, with the performance raising millions of hryvnias, collectively reaching up to $100,000. “The fact that it’s been going strong for two years and continues to do so… That has been deeply rewarding,” says Uryvskyi.

Taking Ukrainian theater abroad

“While its visuals may appeal to international viewers, its cultural and historical context of The Witch of Konotop is undeniably Ukrainian,” says Uryvskyi. “Abroad, it can actually be perceived as somewhat exotic.”

For Ukrainians, telling their own stories is still a challenging endeavor. Despite its immense potential, Ukrainian theater often struggles to gain international recognition. Classic works by icons like Lesya Ukrainka and Taras Shevchenko remain largely unknown to broader audiences. While Ukrainians grow up familiar with the classics of their European neighbors, the rich depth of their own literary heritage remains a mystery to much of the world.

“Perhaps some have at least heard of Franko. He has works that would fit perfectly on European stages,” says Uryvskyi. “The same goes for Lesya Ukrainka. We are still quite underrepresented on the theatrical map of Europe and the world.”

For Ukrainian theater to be heard abroad, it must often resonate with narratives familiar to European neighbors. This has been more evident in some of Uryvskyi’s other works, like Caligula, which appeal to broader, more universal themes. Caligula is a title that is already well-known internationally, Uryvskyi says, and it has a wide impact, especially as a Ukrainian product.

“Something like this resonates more strongly with, let’s say, French audiences than The Witch of Konotop because they recognize the name,” he says. The audience is intrigued by how Ukrainians interpret a story about a dictator, especially in the context of war. “With Caligula, we’ve had more opportunities to engage international audiences at festivals, and they often pick up on very compelling messages,” Uryvskyi adds. “That’s why a play like Caligula has broader appeal than The Witch of Konotop abroad.”

However, Uryvskyi’s team is finding ways to make Ukrainian theater more accessible to global audiences. “We staged The Earth in Kaunas, keeping it deeply rooted in the Ukrainian context but tailoring it to resonate with audiences from anywhere in the world,” he says, adding that theatre needs to adapt to engage and connect, and I believe that’s the key to reaching people beyond borders.

Though The Witch of Konotop has had limited international exposure so far, the performers are excited to prepare for a wider tour. After successful performances in Kraków, Poland, and Chișinău, Moldova, they’re gearing up for shows in Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Geneva, and beyond. “Ukrainian classics exist within a very specific cultural context,” says Uryvskyi. “A play like The Witch of Konotop will be interpreted differently by international audiences.”

But the heart of the story is something that can resonate universally.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)