- Category

- Culture

Ukraine’s Cultural Race to Digitize History Before Russia Destroys It

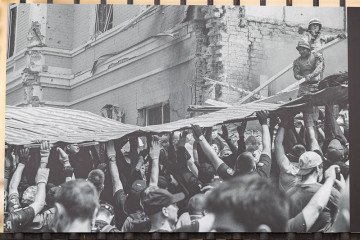

From the Mariupol Drama Theatre, where children sought shelter, to frescoed homes and Cathedrals—no part of Ukraine’s history is safe from Russia’s aggression. Whether by missile or occupation, Ukraine’s centuries-old culture, like its people, is being relentlessly destroyed.

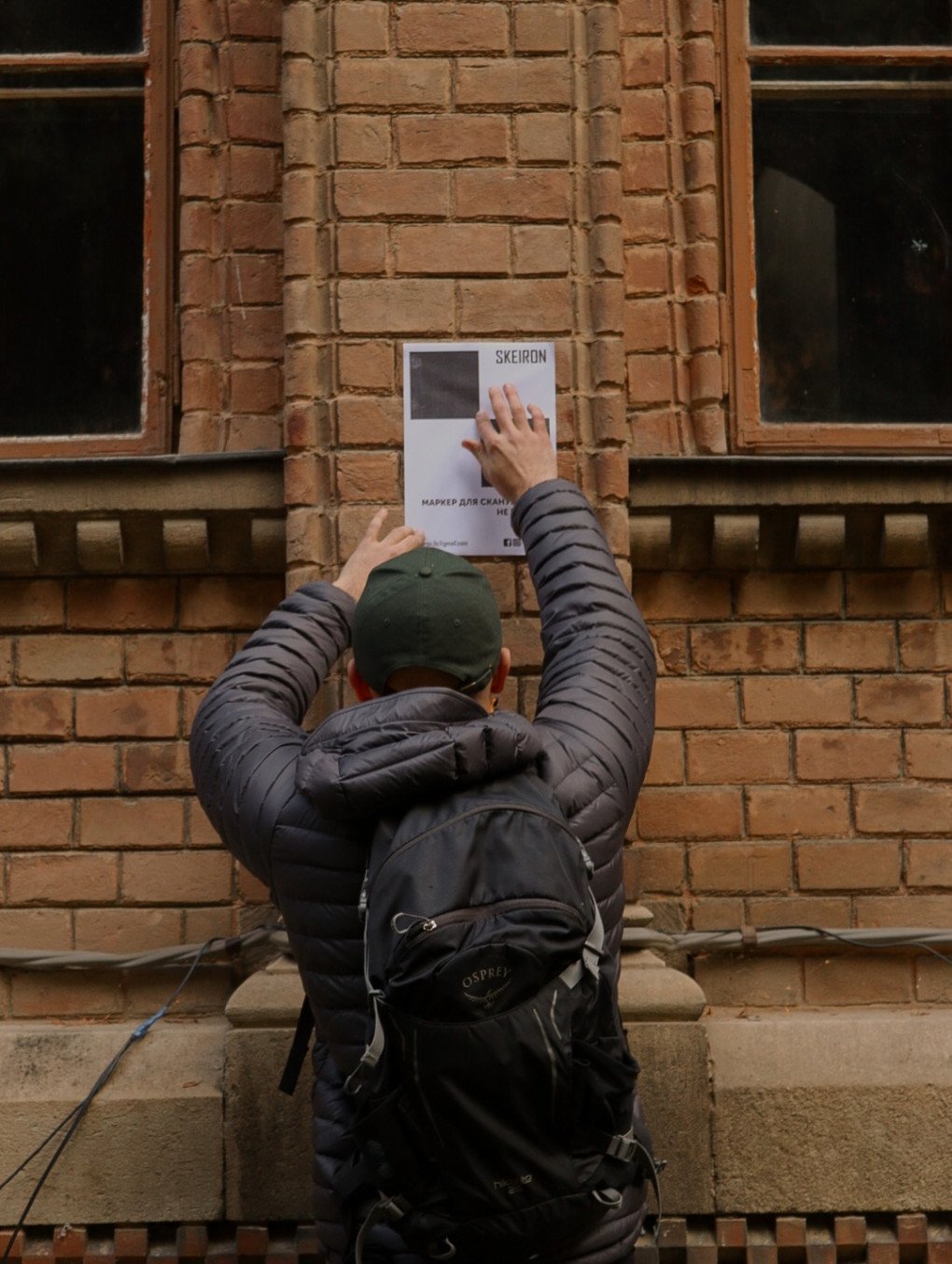

Ukrainian preservationists are turning to cutting-edge tech to immortalize history in a race against destruction. Teams of historians, technologists, and activists have mobilized to digitally capture Ukraine’s most cherished monuments, churches, and historical landmarks before they’re reduced to rubble. Each scan, each 3D model, stands as an act of defiance against Russia’s genocidal war that aims to erase Ukraine and its identity.

We spoke to Kyiv’s Ivan Honchar Museum, the Spilnyi Spadok crowdfunding platform, and the Skeiron 3D scanning studio to understand how Ukraine’s heritage is being preserved amid Russia’s invasion.

The scope of the threat

The UN estimates that the damage to Ukraine’s cultural sector exceeds $3.5 billion.

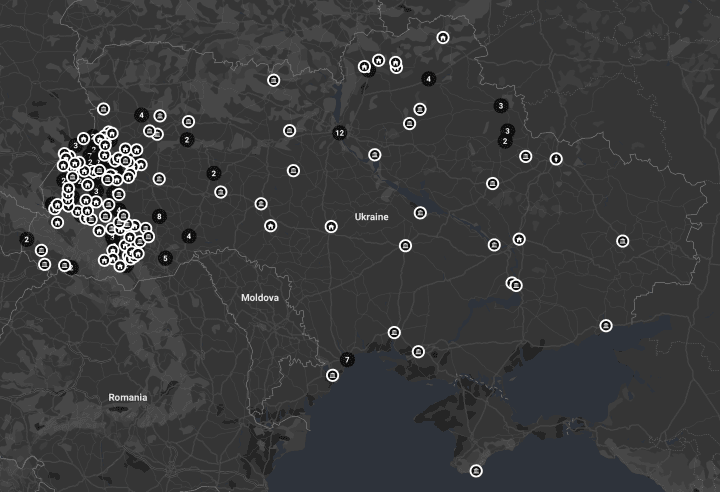

As of 2 October 2024, UNESCO has verified damage to 451 sites since 24 February 2022—142 religious sites, 227 buildings of historical and/or artistic interest, 32 museums, 32 monuments, 17 libraries, 1 archive.

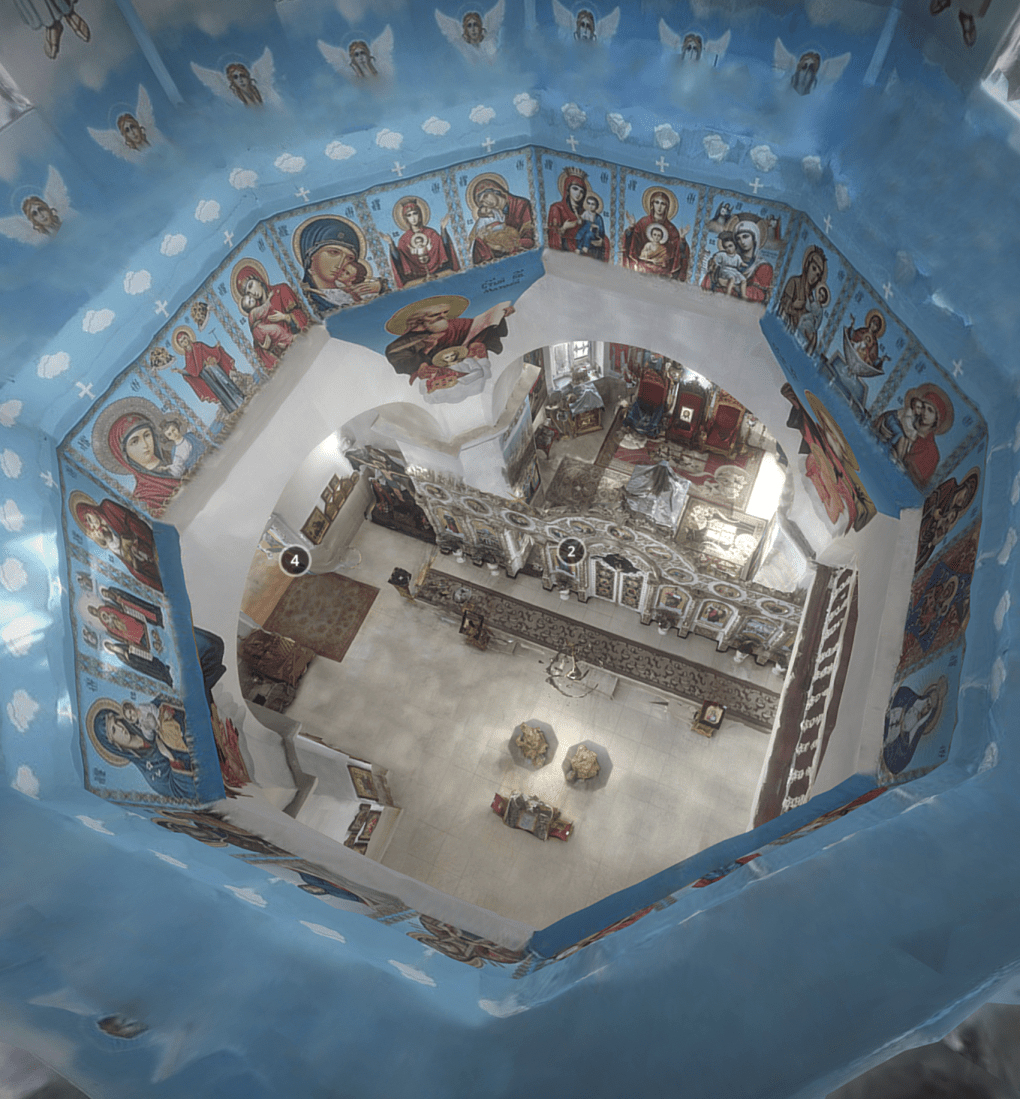

“At times when cultural heritage needs restoration—like digitizing—we’re the ones who handle it,” says Yurko Prepodobnyi, co-founder of Skeiron. What began as a passion project became vital during the war, creating high-resolution images and 3D models. This technology not only records the physical characteristics of these objects but also preserves their context and history for future generations. “We also promote these sites and create new products from them.”

In cities like Mariupol and Kharkiv, theaters, museums, and churches now lie in ruins. The iconic Mariupol Drama Theater, a cultural gem, is now a haunting reminder of what’s been lost—including hundreds of lives.

“Activists managed to document the Mariupol Drama Theater with drone footage before it was destroyed,” says Yurko. “Flying over the entrance, the sculptured part. We managed to reconstruct it in detail. In Bakhmut, we scanned a central church that was later heavily damaged during the war. We’ve already seen the severity of the damage in videos. Metal parts on the roof have flown off. Our pre-war data will aid in restoration efforts after Ukraine’s liberation. Many objects were damaged in Trostianets, Sumy region.”

The destruction of Ukraine’s culture is no accident, it’s part of Russia’s broader campaign to suppress the nation’s heritage. As Moscow attempts to rewrite history, preserving these cultural sites has become a national priority.

“The most vulnerable areas are those occupied or near the frontlines,” says Alina Bozhniuk, co-founder of Spilnyi Spadok, a crowdfunding platform uniting people passionate about preserving and promoting Ukrainian culture. “Russia has been targeting these regions not just now, but for centuries, erasing intellectuals, resettling people, and destroying cultural artifacts. It’s extremely difficult to find items from these areas and going on expeditions is dangerous. There’s almost nothing left from the Crimean Tatars . This cultural genocide has wiped out so much.”

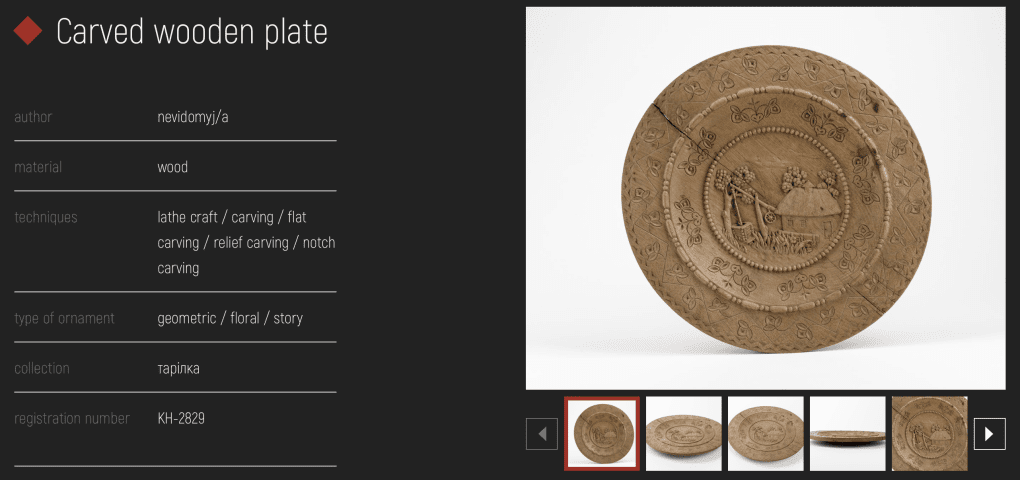

Spilnyi Spadok acquires rare Ukrainian cultural items from the open market for museum preservation, having chosen Kyiv’s Ivan Honchar Museum to preserve the items.

“Most contributors are Ukrainians who want to preserve this genuine heritage,” says Alina. “Many items are still kept in families because they are family heirlooms. Some were made in the early 20th century by people's great-grandmothers or grandfathers. But for various reasons, especially since the full-scale war started, people have had to part with them.”

These objects have become silent witnesses to the war.

Alina Bozhniuk

Spilnyi Spadok crowdfunding co-founder

Hit hard by the war’s economic crisis and job losses, people are forced to sell their cultural items for money. In frontline areas, these artifacts are being destroyed alongside homes, and when families are lost, neighbors sometimes step in to save what remains. Fleeing Ukrainians also face tough choices—larger items like ceramics or candle holders are simply too big to take, so they sell them, fueling a growing secondary market for these cultural treasures.

“A key condition of our project is that these items be digitized first,” says Alina. “If anything were to happen to the museum, there would be a record.”

“We’ve even broken some of our usual procedures for this project,” says Myroslava Vertiuk, Deputy Director General on Intangible Cultural Heritage at The Ivan Honchar Museum National Center of Folk Culture. “Normally, new acquisitions don’t get digitized right away—they go into a queue, with a set priority list. But the Spilnyi Spadok project is different. If people don’t see their donated items digitized and online fast, it could hurt their enthusiasm. They donate something today, and by tomorrow, they want to see it showcased on the museum’s website, complete with a description. That instant payoff keeps them motivated and proves we’re not just tucking their contributions away.”

What Ukraine preserves

“Some asked us to handle specific objects because they recognized the importance of preserving these sites—like St. George’s Church in Lviv or the wooden churches listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, near the Polish border,” says Yurko.

Skeiron extensively digitized sites in the Volyn region, including Lutsk’s Lubart Castle and key city locations. They also scanned the Kamianets-Podilskyi fortress, churches in Chernivtsi, Chernivtsi National University, and Kyiv’s Saint Sophia Cathedral. At the Culture Ministry’s request, they digitized several ancient heritage sites in Chernihiv.

“Chernihiv is an extraordinarily ancient city,” says Yurko. “We collected data not only about the digitization process but also about the objects themselves.”

“Ukrainian culture is generally always inspired by something from the people,” says Alina. “What do I mean by that? It’s when people are self-taught. They don’t finish art schools or institutes; they create household items and more by themselves at home. This has been preserved in our culture. It still exists.”

Such works fall under “naïve art”—a raw, authentic form. In the early 20th century, this self-taught creativity thrived in both villages and cities across Ukraine. It wasn’t just art—it was a way of life. People crafted everything from intricate embroidery and vibrant textiles to pottery and hand-carved wooden tools, often using skills passed down through generations. While some techniques have faded in certain regions, many Ukrainians still keep these crafts alive, continuing to shape the nation’s artistic spirit today.

We encourage people to explore their own family histories and regions because there’s so much information that isn’t documented by state institutions.

Alina Bozhniuk

Spilnyi Spadok crowdfunding co-founder

“One woman was the daughter of a Ukrainian Sich Rifleman ,” Alina explains, showing the items made by Ukrainian women exiled to Soviet labor camps in the late 1940s. From her, they acquired a drawing album, an embroidered blouse, and an embroidered painting of a Ukrainian village, a common depiction of a paradise garden in folk art. Another preserved item is a 150-year-old wooden icon. “In Ukraine, there’s a strong tradition of making icons for personal use, not for churches,” says Alina. These pieces can be masterfully done, despite the lack of formal education.

Spilnyi Spadok’s work spans Ukraine and beyond, preserving the heritage of displaced groups like the Lemkos . This tragic resettlement scattered unique Ukrainian cultures across the country, as mountain communities were relocated to unfamiliar steppes or Donbas, struggling to adapt while trying to save what little they could of their heritage.

“Some things were preserved by those who somehow managed to stay, or by those who left but kept their belongings,” says Alina. “These items also help us tell this story. “

Spilnyi Spadok team has also rescued items from families affected by other Soviet-era policies. When reservoirs were built, hundreds of Ukrainian villages were flooded, forcing families to flee with whatever they could carry. “We saved a pair of wedding shirts from a resettled family in Bakota, one of the villages submerged by the Dniester Hydroelectric Station,” Alina shares. “We also preserved a rushnyk from a displaced family near the Kyiv Reservoir.”

Another example of a rescued rushnyk comes from the frontlines—a large 3-meter one, serving as a tablecloth, from the Kharkiv region embroidered by a great-grandmother of a woman whose husband is now serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

If these pieces end up in Russian hands, they can be used to warp history.

Alina Bozhniuk

Spilnyi Spadok crowdfunding co-founder

“The urgency of war has pushed us to accelerate digitization because it’s one of the only ways to preserve the collection,” said Viktoriia, the Ivan Honchar Museum Chief Curator. “We actively started digitizing around 2018. Digitizing even a small collection takes a long time. We are working towards digitizing as quickly as possible, at least the main collection.”

However, given the circumstances of the war, the museum strives to digitize the entire collection.

The role of digitization and international support

To protect artifacts from looting and destruction, Ukraine’s Culture Ministry launched multiple initiatives to preserve and promote the nation’s culture, like building an electronic catalog of museum treasures, creating the Register of Ukraine’s Museum Fund, or partnering with Google’s Art & Culture project, “Ukraine is Here,” supported by First Lady Olena Zelenska. The aim? To provide free, state-backed tools for easy, transparent access to Ukrainian cultural heritage.

“In mid-2020, we began collaborating with international organizations to get more support,” says Yurko. “Unfortunately, soon Google will remove some of the support: when searching you won’t be able to see 3D models, but some models are still searchable.”

Still, many objects do pop up in Google searches, like the 3D model of St. Sophia Cathedral. Skeiron’s vision was simple: upload all their models to Google, making them easily accessible for anyone looking to explore and research these digitized treasures.

“We often receive emails from historians and architects asking for data,” says Yurko. “We love collaborating. Several people have already completed their thesis projects, or simply requested the data for their work.”

To better organize the artifacts, Skeiron is developing a classification system with filters for regions, site types, and objects. “Ukraine’s diversity makes it essential to showcase different religious and non-religious groups and make that selection possible. Surveyors’ contributions, like laser scanning or drone photogrammetry, will be marked, ensuring transparency and recognition.”

The ultimate goal is to pass this platform to Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture. “For now, though, we’re focused on building it,” Yurko says.

“It’s impossible to hold exhibitions right now,” says Alina. “Digital artifacts allow us to showcase items online. Many of the pieces we collect tell stories that resonate globally, not just in Ukraine. We believe international audiences will see the value in preserving these items and support our efforts.”

Spilnyi Spadok collaborates with experts like the Ivan Honchar Museum. “We also maintain communication with local experts when there’s doubt about an item’s authenticity or value, especially from certain regions.”

“Scientific accuracy is crucial in digitization, but we set the bar equally high for aesthetics,” says Myroslava. “It’s not just about preserving artifacts—it’s about how we bring our heritage to life.”

While the museum can’t preserve everything, it takes great care to showcase what it has with precision. “Each digital image needs to capture the essence of Ukraine’s traditional culture, just like an exhibit,” Myroslava explains.

Every image should stop you in your tracks. Our digital archives mustn’t be just photos—they need to be well-classified and presented scientifically.

Myroslava Vertiuk

Deputy Director General on Intangible Cultural Heritage at The Ivan Honchar Museum

Currently, about 50% of the Ivan Honchar Museum’s collection is available online for public viewing, and researchers can request additional materials. “We handle each request individually and provide digital copies as needed,” says Viktoriia.

When the “Ukraine is Here” project launched, the museum decided to digitize 1,500 of its finest pieces. “The project has drawn interest from various European institutions, which have requested our materials for use in publications, scientific journals, and art books.”

To bring these cultural treasures closer to the people, the Ivan Honchar Museum partnered with the Ukrainian embroidery brand Etnodim—whose vyshyvankas have been worn by President Zelenskyy himself. Etnodim created a collection of embroidered shirts and dresses inspired by fragments preserved in the Honchar Museum, many of which are too fragile to restore, breathing new life into Ukraine’s textile heritage.

Yet, one of the museum’s strategic goals is to integrate its work into the global academic process, not just the cultural sphere. “We want to open our archives to European researchers,” Myroslava says. “The growing interest in Ukrainian culture, especially since the full-scale invasion, has given us a new way to present ourselves—not just in the news about the war, but through our heritage.”

By combining digitization with community collaboration, Ukraine is not only preserving its cultural treasures from Russian destruction but also making them accessible to future generations and researchers around the world.

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)