- Category

- Culture

The Enduring Legacy of the Kharkiv School of Photography, Capturing War in Ukraine Today

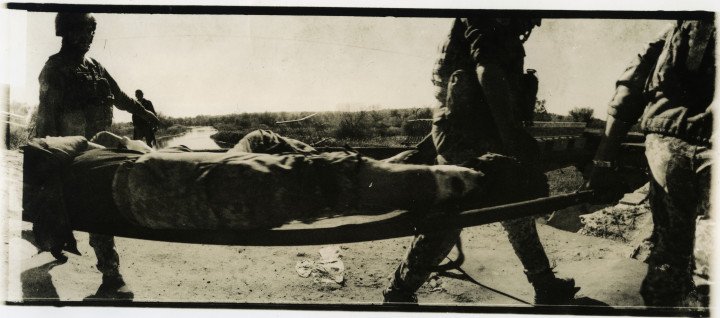

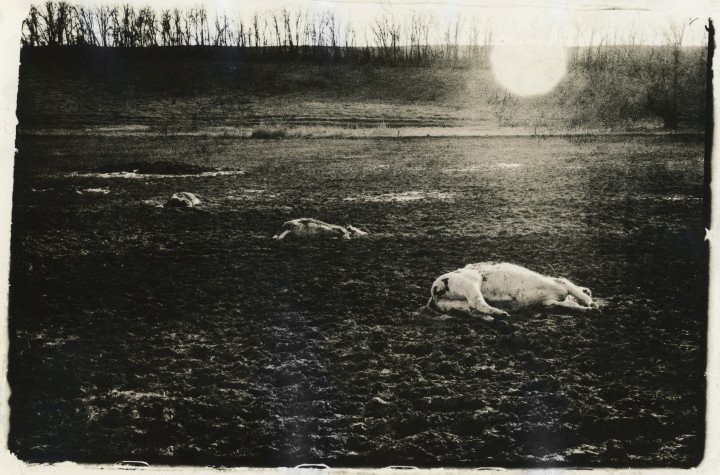

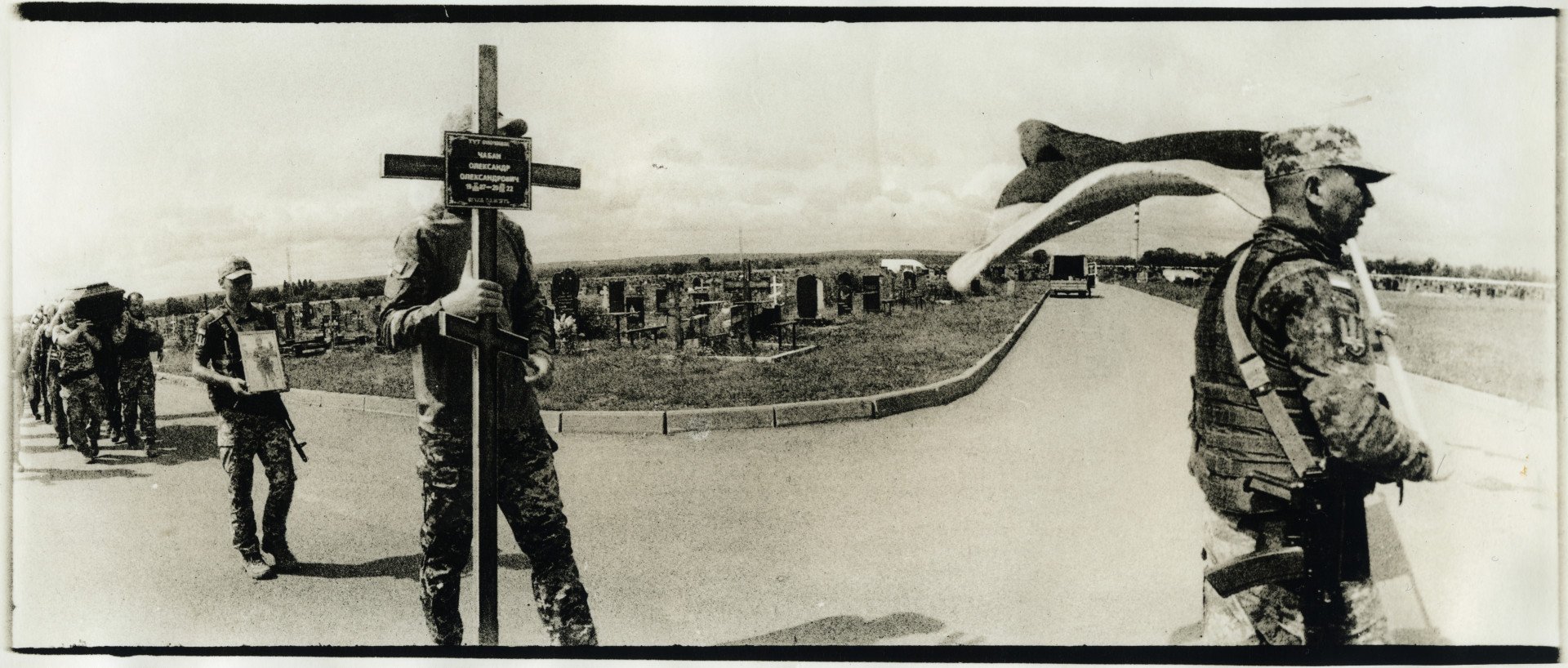

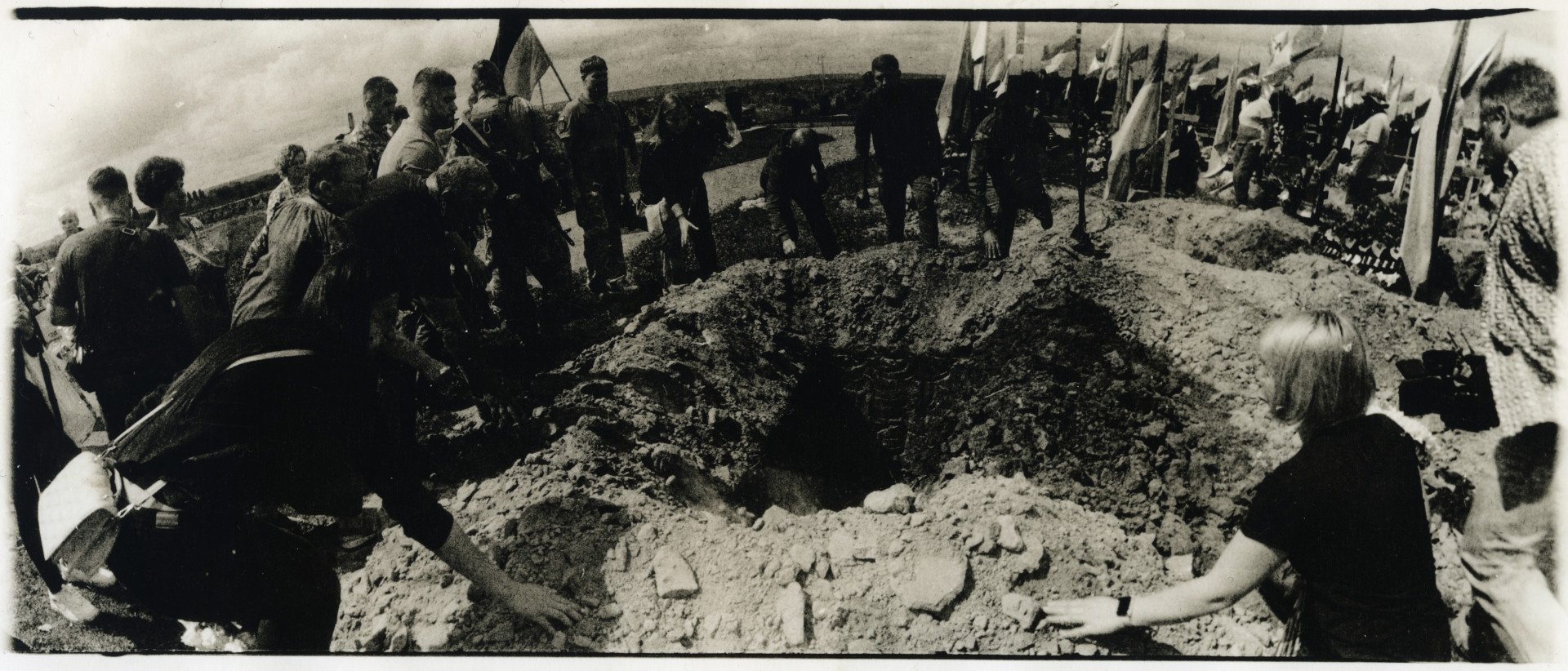

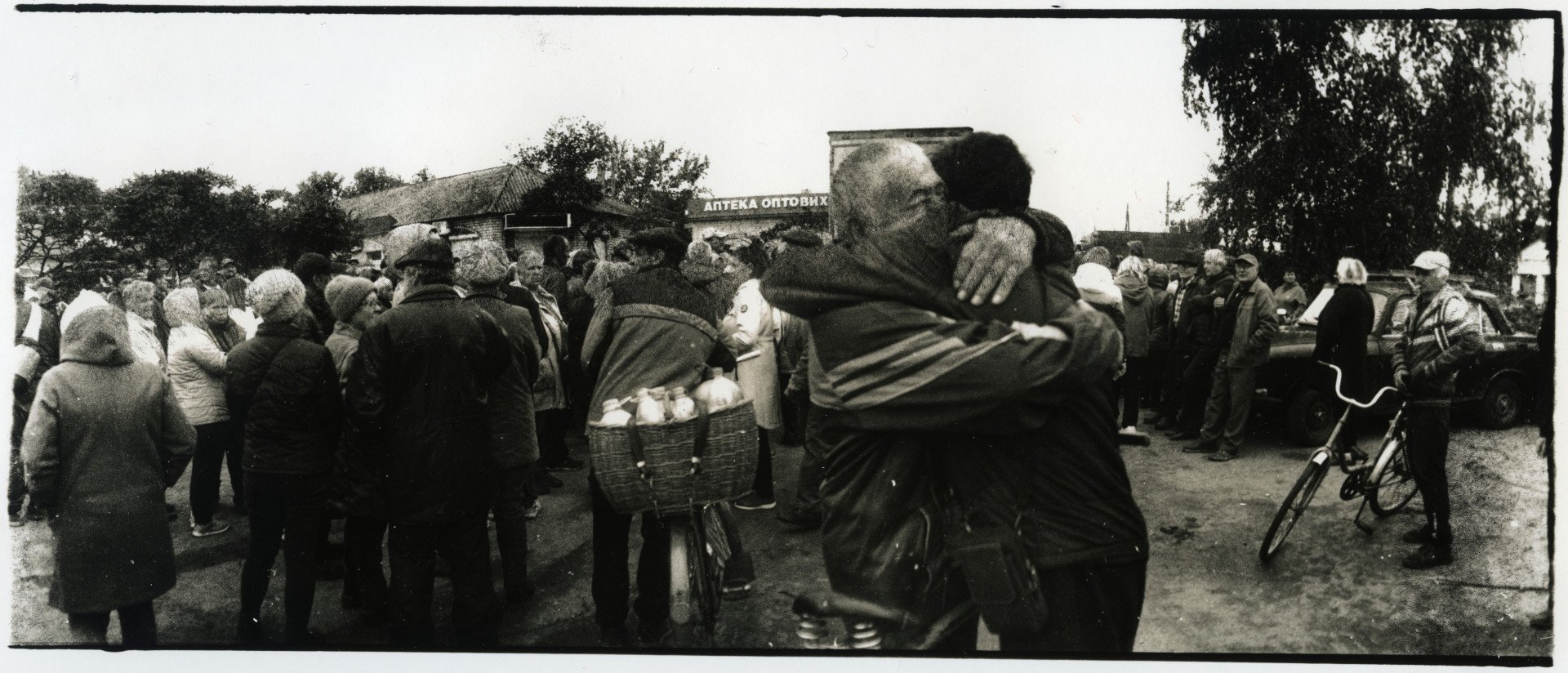

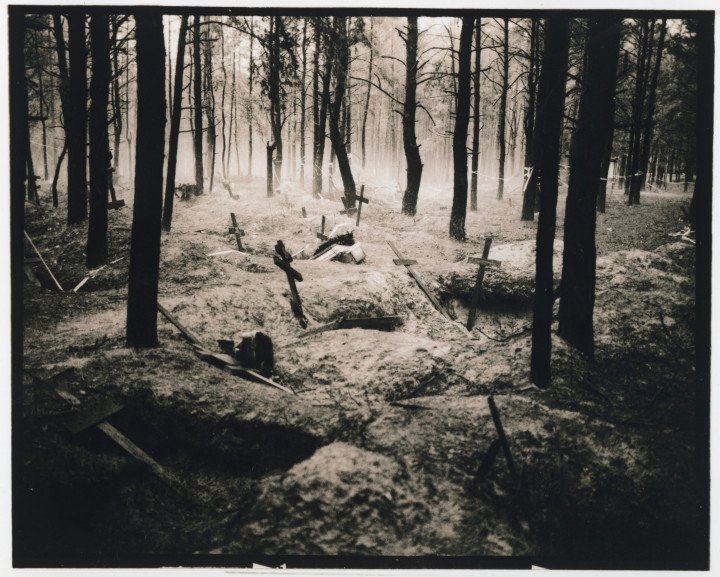

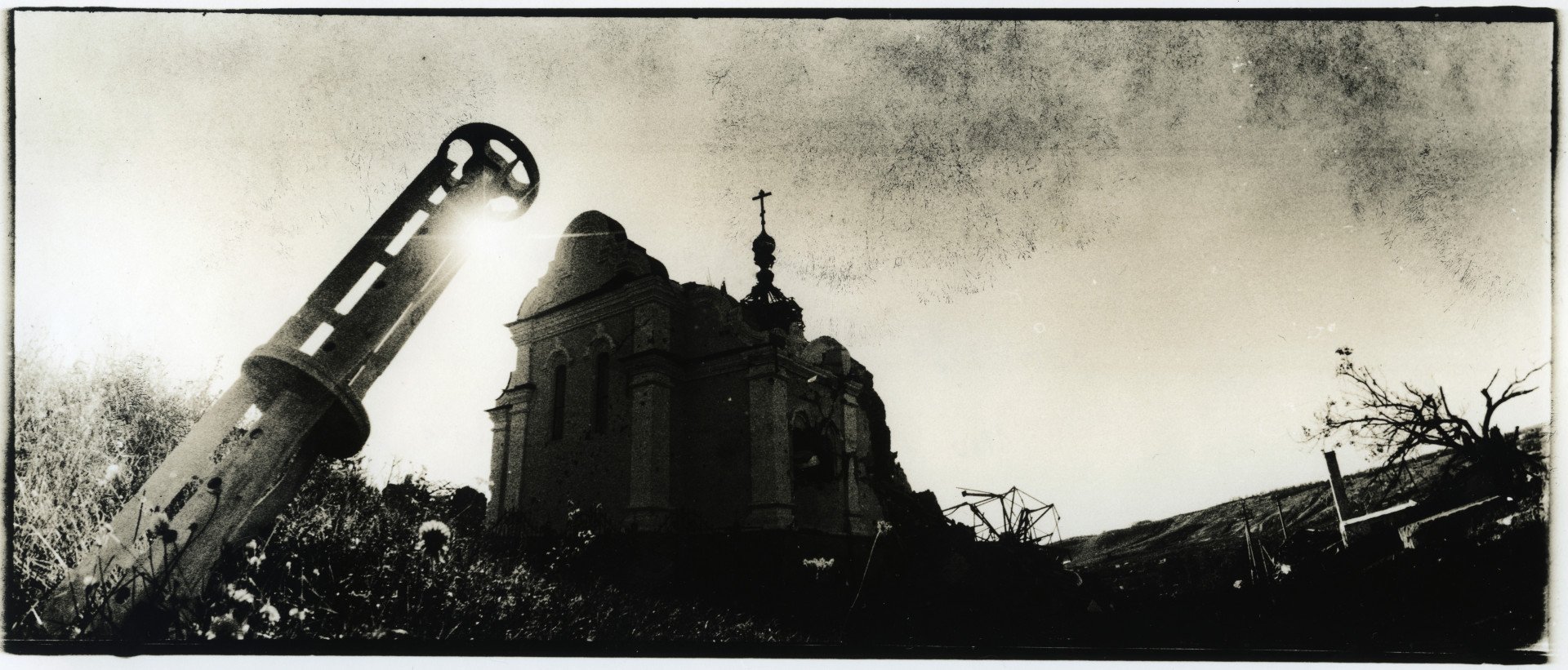

How descendants of an underground, non-conformist photography movement—founded in Kharkiv in the 1970s—continue to capture war in Ukraine today.

The term "Kharkiv School of Photography" (KSOP) originated from the ‘Chas’ (time in Ukrainian) group that was established in 1971 at the Kharkiv Regional Photo Club. KSOP was an underground, non-conformist movement that reacted against the Soviet socialist realism art style with the striking imagery they created, both theme-wise and technique-wise. In 1975, the authorities shut down the photo club. However, the members continued to stay connected and collaborate, carrying out joint shoots and exhibitions until the late 1980s.

Today, new Kharkiv photographers continue the legacy of KSOP, and the movement lives on. We met and interviewed Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, a representative of the third generation of KSOP, who captures life amid Russia’s war in Ukraine these days:

“The defining feature of the Kharkiv School of Photography is its focus on social themes. All Kharkiv photographers have extensively worked with social topics. Technically, this also includes work with printed photographs, collages, drawing on photographs, etc. Overall, this type of photography emphasizes aesthetics and how the photograph engages the viewer—quickly, like a strike."

“To work within this aesthetic, it's important to be in that environment, in Kharkiv. The city, and the social context leave their mark. However, when the Kharkiv School of Photography inspires someone, it’s possible to stretch the influence a bit. Serhii Melnychenko drew a lot from Roman Pyatkovka; his work sometimes also reflects the impact of the Kharkiv School of Photography, even though it’s more... the Mykolaiv School of Photography (laughs)”

"When there’s a situation and a concentration of events, I don’t keep track of the film at all. On a single day, I might shoot 10 rolls of film. From those, I expect to get 5-10 good shots. I always end up with more, but when I come back, I often don’t like any of them. There’s no time gap between when I shoot, develop, and print the film... While I select I see that it’s beautiful, but to choose the best ones, time needs to pass. I need to step away from the situation a bit and forget how it was. Then I can return to the archive and select something different, something I didn’t notice before."

“Talking about the aestheticizing of tragic events... For me, as a person, tragedy exists; there is empathy when I see news about casualties and attacks. It affects you psychologically, but when you start photographing it, you abstract yourself from it and seem to shoot through the lens of composition. You see the image compositionally and work from that perspective. You distract yourself from everything; it feels almost like a movie.”

“Each year, it gets harder and harder to capture anything. It’s like in the Amazon jungle—everything wants to kill you. At the beginning of the war, it was one thing, but now everything is flying around, drones, MPVs, explosions. You might end up without photos, without cameras, injured. Then you need time to recover.”

“I use several cameras—Olympus Pen half-frame cameras, Olympus X full-frame cameras, Leica M6, the Horizon panoramic camera, and the Mamiya 7 medium format camera, which has a 6x7 frame size. I develop all of this at home.”

“The technique I use for printing allows for some variation in contrast and other elements, which can add a sense of imagery and artistry. But you see, when there is already a formally beautiful photograph in the negative, no matter what method you choose, it will still work on the viewer.”

“You know, there’s a thing—there are trips where you go just for the experience, to challenge yourself, but there’s a 95-100% chance you won’t get any good shots because it’s very dangerous. And then there are trips specifically for photography.

But I think for a photographer, the most important thing is to stay alive and get the shots, rather than just proving yourself. It’s possible to do both, but no photograph is worth your life.”

“Now there isn’t any group where we all gather anymore. We rarely communicate because many people have left Kharkiv. Maybe only three people are left who are currently working. It’s me and the younger generation. We can get together just to chat.”

Photos and words by Vladyslav Krasnoshchok. The photos were taken with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

-33441405bda6df220cc127a38043a08d.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)