- Category

- Anti-Fake

Seven Myths About the Soviet Union. Separating Fact From Fiction

In 1984, Orwell wrote, “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.” And so it was in the USSR, a dystopia paralleling the fictional Airstrip One where reality and official rhetoric inherently contradict one another.

Here, we present the seven most common myths that painted an idealized image of the Soviet Union, hiding a legacy of control, repression, and hardship that endures to this day.

Myth 1: Healthcare was universal and specialized

Although the USSR had twice as many healthcare workers as the US, they regularly lacked drugs, anesthetics, and sterilized instruments. Disposable needles were unknown. By 1980 there were only 5 CAT scan machines across the entire Soviet Union—the population at this time was over 262 million. Following the Chornobyl disaster, there were so few available medical supplies, that the Baxter International Corporation of Chicago was voluntarily supplying surgical gloves and blood separating machines.

The government’s indifference to environmental hazards and work conditions also saw an annual 5-6% increase in the prevalence of birth anomalies. 200,000 children were being abandoned at institutions yearly.

Between 1949 and 1989, the Soviets carried out 456 secret nuclear tests at just a single location in Qazaqstan .

Nuclear fallout from the test sites, contamination and exposure from the poorly equipped workers (who were viewed as disposable) resulted in decades of preventable cancers and death.

Families were never told about the nuclear tests, and survivors and victims didn't receive compensation. To this day, 40% of the population suffers from chronic illnesses; rates of cancer and miscarriages remain high.

Victims of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster were also limited in their compensation, needing first to pass commissions that assessed their “level of victimhood”. 65% of the compensation was never paid out and the burden of proof—that their illness was a result of Chornobyl—lay on the victim. Due to the endless obstacles of the bureaucratic process, many simply gave up.

Access to healthcare and medicine was inherently rooted in resources—both financial and personal connections. In their study, “Anomalies in Soviet Healthcare,” University of Chicago professors Dr. Gary Albrecht and Dr. J. Warren Salmon found that, “Members of the Communist Party, residents of large urban areas, particularly Moscow, and those who held more privileged positions in society had access to a series of polyclinics and hospitals that are superior.”

Kremlin officials had their own hospitals and those at the very top reached outside the Soviet apparatus to the West to access procedures and medicines that were either unavailable or in short supply under the Soviet Union.

Using the health of its citizens as a measure, the USSR was not a developed state. The infant mortality rate was 3x higher than in Western Europe. Widespread infant illness was linked to contaminated formula; even though the problem was recognized for several years, it went unresolved.

Myth 2: Abortion was legal, safe, and accessible

Abortion was legalized in the USSR in 1920, however, the state initiated “special abortion commissions” whose main responsibility was to establish a hierarchical approach to abortion.

Women with children were the last to qualify for access to abortion; later, under Stalin, a special tax was introduced for women with less than 3 children.

The conditions in the clinics were abysmal. Women were given abortions without anesthetic or any personal care, with several abortions being performed at once.

The following is just one witness recollection from historian and gender studies scholar Amy E. Randall’s research in the Journal of Women’s History:

“If a woman has made up her mind to have an abortion, she is in for a round of tortures. The abortion clinic on Lermontov Prospekt is a monstrous institution—a slaughterhouse, as women themselves call it. The treatment capacity of the clinic is two hundred to three hundred patients a day. The women are put in lines in front of the operating room. Two and sometimes six women are operated on at the same time.”

It was not uncommon for women to faint—some were tied to the cot during the procedure. Some women underwent ten, even twenty abortions over the course of their reproductive years due to non-existent sex education & contraception.

In Lenin's view, birth control was a bourgeoisie tool “against the proliferation of the poor” and abortion became the primary form of family planning. Because women lacked access to contraceptives, 10-16 million abortions were performed annually. The average woman underwent 6-12 abortions during her childbearing years, often resulting in uterine damage.

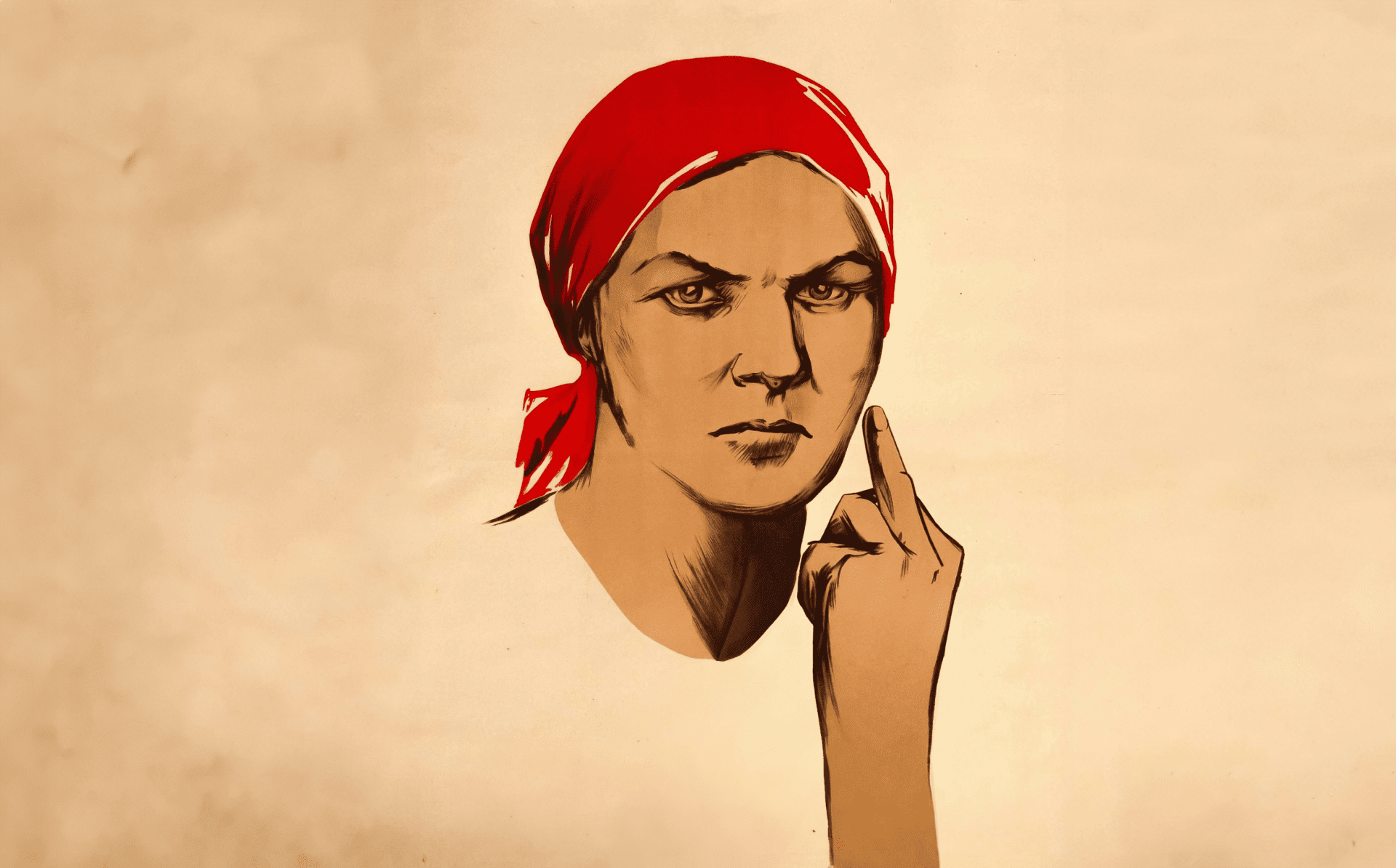

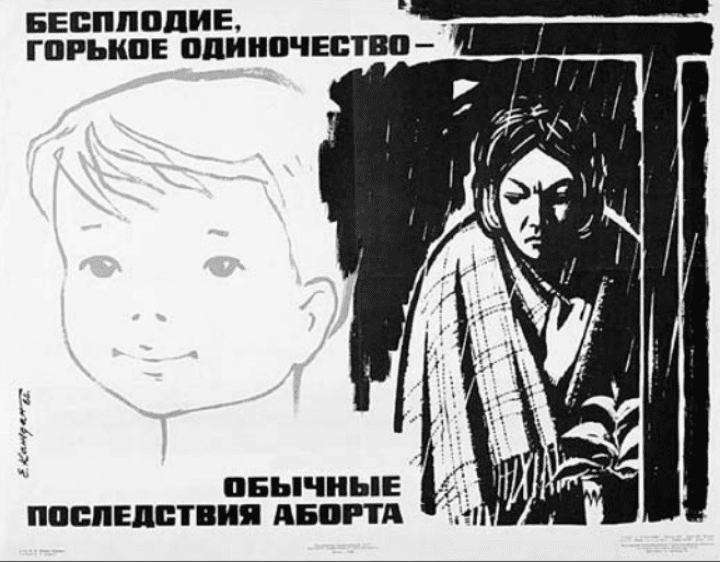

Despite abortion being legal on paper, aggressive pro-life propaganda was rampant. Anti-choice posters included headlines such as: “[And to think that] I wanted an abortion…” “Abortion will deprive you of happiness,” “Infertility and bitter loneliness are common consequences of abortion” and “Stop! Abortion seems necessary now, but remember that it can forever deprive you of the happiness of motherhood.”

![Soviet-era anti-abortion poster reading “[And to think that] I wanted an abortion…” (Source: Babel) Soviet-era anti-abortion poster reading “[And to think that] I wanted an abortion…” (Source: Babel)](https://storage.united24media.com/thumbs/x/1/96/42f4d37b26fe287999cc5d33a00b7961.jpg)

Those who carried their pregnancies to term and placed their babies for adoption, were not treated with any more understanding.

The press began to call birth mothers "cuckoo-mothers" and the Committee of Soviet Women wanted cuckoo-mothersʼ passports stamped, branding them, and comparing them to criminals.

It was also suggested that a woman's workplace be notified if she ended a pregnancy in any way.

After the 1936 abortion ban, state propaganda began to play on womenʼs sense of femininity, encouraging women to “cultivate their femininity [...] defined as womenʼs innate capacities to nurture and serve”—this message was pervasive across print media, radio, and within the arts. Women were not only required to work and parent—but also be attractive to the male gaze.

Myth 3: The Soviet education system was the best in the world

In an environment so heavily informed by propaganda, or in Orwell’s words, double-think, it’s only natural that indoctrination begins at an early age. Soviet educational practices heavily subscribed to fear-based and labor-intensive approaches rooted in morality.

Students were required to stand up when a teacher entered the class room and punishments for wrong answers involved various forms of shame and humiliation. Buildings were crumbling, textbooks outdated, teachers under-motivated, and 40% of schools in the Soviet Union lacked indoor plumbing. All aspects of learning were tightly controlled and overseen by party officials.

It is unsurprising then, that even among all the boasting of the world’s best literacy rates, only 20% of students in 1940 advanced from 7th grade.

Out of those who did graduate from 10-year schools, only 1 in 5 went on to pursue higher education, limited by competitive union-wide entry exams and fees amounting to 300-500 rubles.

The scope of education was also limited primarily to industry, construction, agriculture and health—less than 10% of universities in the Soviet Union focused on the arts or social sciences.

Myth 4: Equal pay for equal work

While it’s true that nearly all women worked outside of the home, they were far from the idealized emancipated or liberated image of a working woman. Instead, women were mobilized by the state to strengthen the construction of a planned central economy. Unlike men, women shouldered the double burden of underpaid work and unpaid domestic labor.

Although there were state cafeterias, nurseries, and laundries—they were primarily staffed by women, who continued to perform those same tasks within the home as well.

State laundries only accounted for 2% of the domestic burden; state cafeterias for only 5%

As Dr. Melanie Ilič, a professor of Soviet history at the University of Gloucestershire, noted, "womenʼs participation in the Soviet economy did not provide for womenʼs liberation. Rather, it simply expanded the spheres in which women could be exploited.”

Gender-based discrimination was rife in Soviet workplaces with women averaging only 65% of men’s earnings. The state understood that widowed or abandoned mothers would accept mere rubles out of desperation; collective bargaining or collective self-organizing was prohibited. By 1956, the state had outlined over 2000 different skill levels, a tool used to suppress the potential for wage increases since skill assessment was discretionary and involved bribery.

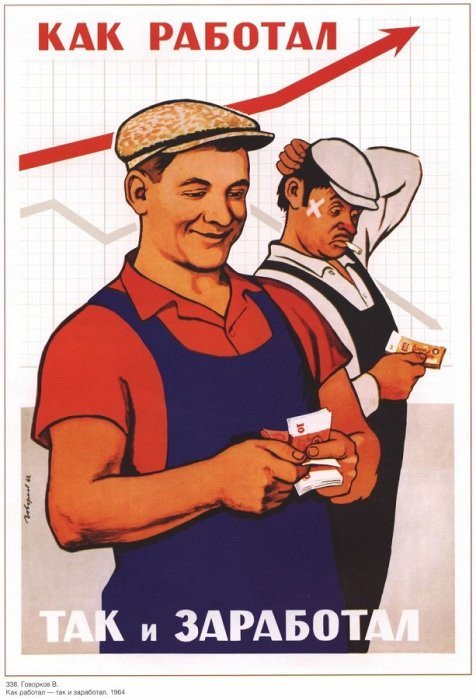

Analysis of Soviet propaganda posters also provides valuable insight on the discrepancy between official and subliminal Soviet messaging.

This 1964 poster, for example, can roughly be translated as “Your pay reflects your work performance”—a point that few would argue with, yet the contrast between the well-paid blonde with Slavic features and the darker-skin, black-hair man with Caucasian features reveals the hypocrisy behind the party’s carefully curated statements:

Official party rhetoric claimed that all people were equal in the USSR—but some were more equal than others.

Myth 5: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”

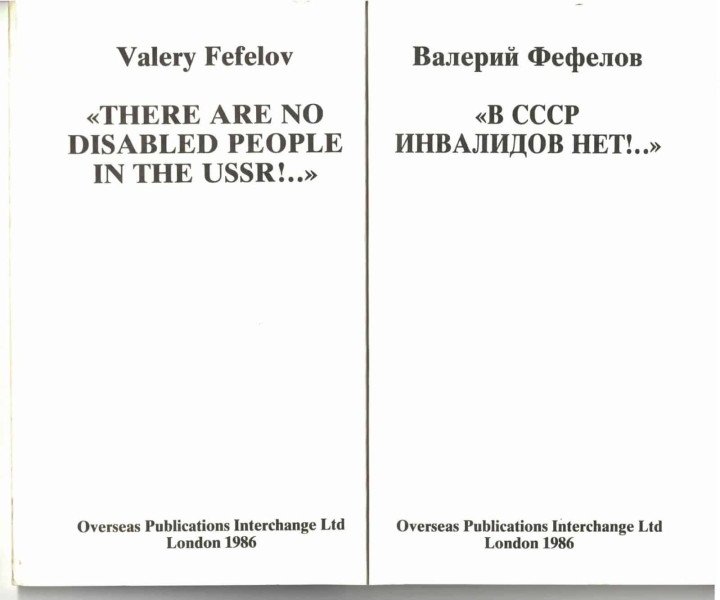

The USSR is often romanticized as a utopia that fulfilled the needs of its people, guided by the principle “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” In reality, entire groups—particularly people with disabilities—were marginalized, institutionalized, forcibly sterilized, and, in some cases, executed.

Leonid Zakovsky, a Soviet police chief responsible for the execution of hundreds of people, used to say, “Why are you whining about your sick and your crippled [...] if someone is crippled or maimed, send him to be shot and that's it. No problem.”

Those who survived had no material or financial support. A person who required a wheelchair was entitled to receive a free one from the state for 5 years—however, the wait time was often years and the chairs were bulky, heavy and impractical. Buying one from abroad was both financially impossible, and illegal.

Following World War II, the population of people with disabilities, in particular amputees, increased exponentially.

The Soviet language had a new name for this demographic: Samovary or more specifically, “human stumps on little wheels.”

It was not uncommon to see injured veterans at metro and train stations, clad in medals, selling the last of their possessions, or begging.

At this time, there were approximately 2.6 million amputee war veterans (this figure doesn't account for all other disabilities).

It wasn’t until 1968 that people with disabilities were granted permission to work jobs outside of an institution setting; still, approximately only 1 in 35 were employed.

In the 1970s there were thousands of institutions (1500 officially recorded as of 1979) that housed hundreds of thousands of disabled people in warehouse-like conditions across the USSR.

It wasn’t uncommon for young disabled people in their 20s to be institutionalized in senior-specific homes with people who were dying, or already dead.

Myth 6: Motherhood was generously compensated, women’s domestic burden—alleviated

In 1980, women (including single mothers) received 5 rubles monthly for one child, 7.5 rubles for two children, and 10 rubles for three children.

These amounts remained unchanged since the late 1940s. The monthly poverty line was 66 rubles.

Instead, the state relied heavily on coordinated propaganda and the issuing of meaningless “mother medals” to encourage women to procreate in unsustainable conditions.

As with all other facets of life in the Soviet Union, motherhood was hierarchized:

Mother Heroine was awarded to women who birthed and raised 10 or more children, Order of Maternal Glory to those with 7-9 children, and Medal of Motherhood to those with 5-6 children.

In August 2022, Putin reintroduced the Mother Heroine award established by Stalin in 1944.

This return to Soviet-era practice (which had been abandoned in 1991) was unsurprising considering that earlier couples in certain Russian regions were eligible to win refrigerators and other prizes if they “birthed a patriot” on June 12th, exactly 9 months after the September 12th “Day of Conception.”

Myth 7: All cultures were equally respected

The fallacy of this sentiment can be summarized entirely in Stalin’s May 24th, 1945 toast: "To the health of our Soviet people—and above all—the Russian people," which reflected the Kremlin’s position of distinct Russo-centrism across all spheres of daily life.

Although the formal party position was predicated on internationalism and the creation of a “pan-Soviet” citizen, Stalin shared the views of Russian nationalists and heavily prioritized the interests of ethnic Russians.

Russification—the process of forced assimilation, name changes, language bans, and terror campaigns—was a foundational and ever-present practice imposed upon all the countries under Russian occupation. Russian was the official language of the Soviet Union and the only language of operation in all major academic, scientific, and cultural institutions. While nearly all Soviet citizens learned Russian from a young age, ethnic Russians who relocated to other republics rarely learned the local language.

In Sakartvelo , when Russian was declared the official language, all textbooks and dissertations written in Georgian were banned and it was forbidden to defend a PhD dissertation not written in Russian. Non-Russian Soviet citizens wishing to participate in, and contribute to, public life were forced into colonial linguistic and cultural assimilation.

In the Baltic countries, Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians had no choice but to receive all government services in the occupiers’ language—Russian. In many regions in the Baltics, the local populations were pushed out by mass deportations and the Soviet Union’s settlement of ethnic Russians; by 1989, Latvians represented only 52% of Latvia’s population—ethnic Latvians became minorities in Riga and six other cities.

Similar patterns of populating ethnic Russians to replace killed or deported local communities were especially prevalent in Qazaqstan after the 1930-33 man-made famine that killed 2.3 million Qazaqs and in Ukraine, after the 1932-33 man-made famine Holodomor that killed approximately 5 million Ukrainians.

In 1926, Ukrainians comprised 21% of the Soviet Union and were the largest ethnic population. It comes as no surprise that Moscow’s brutal policies of the 1920s and 30s targeted Ukrainian identity with particular force. Under Soviet occupation, Ukraine became one of the most russified Soviet republics, in part because Russians viewed (and continue to view) Ukraine as nothing more than an extension of Russia.

Traditionally Ukrainian (and many other non-Russian) last names were altered with ov/ova and ev/eva suffixes, folk traditions such as Malanka were outlawed, the Ukrainian language was banned more than 60 times tracing back to the Russian Empire and reduced to so-called “village speak,” and Ukrainian-speaking creatives and intellectuals were killed during the Executed Renaissance.

Propaganda imagery presented Ukrainians as lazy and feeble-minded in contrast to the robust Russian workers typical to the socialist-realism style of the time.

Here, this 1963 poster (written in Ukrainian to specifically target Ukrainians in the west of Ukraine) says: “Do not sleep during the harvest—you’ll miss the crop gathering!” Of course, a fat and lazy stylized man is depicted in a recognizable vyshyvanka, immediately signaling his Ukrainian identity:

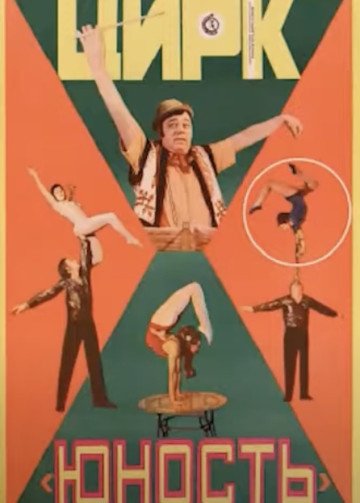

In this 1964 circus ad, the “clowns” are simply men in a Ukrainian vyshyvanka and in another circus ad, this time from 1978, the central object of entertainment is depicted in traditional attire native to the west of Ukraine:

In this way, Soviet propaganda posters give us insight into the absurdism of Russia’s colonial relationship with Ukrainians—the Russian worldview sees us as simultaneously a “brotherly nation” belonging to them as well as an enemy from within that must be destroyed.

Orwell opens Animal Farm by writing, “Let's face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short.” For a man who never set foot in the Soviet Union, he aptly captured what it meant to live through—and often die because of—Moscow’s autocratic regime that surpassed the terror of dystopian fiction.

-8fda54010650befcec1e2c4d694c566b.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)