- Category

- Life in Ukraine

As Russia Builds Prisons in Occupied Ukraine, Its Tactic of Control Through Incarceration Spreads and Mutates

For centuries, Russia has tried to eradicate dissent—including in territories it colonized—by sending political prisoners to penal colonies across its empire. Today, this system has mutated once again—this time, in newly occupied Ukraine.

“You must know: we are not your weak point. If we’re supposed to become the nails in the coffin of a tyrant, I’d like to become one of those nails. Just know that this particular one will not bend,” wrote Crimean-born Ukrainian film director Oleh Sentsov in a letter smuggled out of a Russian penal colony in Yakutia in 2016.

Sentsov was sentenced to 20 years in prison back in 2015—alongside Oleksandr Kolchenko, a Crimean anarchist, who received ten years on terrorist charges for allegedly setting fire to offices of the Russian ruling political party in Simferopol and attempting to do the same to a statue of Lenin.

Together, they were some of the first political prisoners detained on fabricated charges in Russian-occupied Crimea, a practice that has only intensified since.

A year into its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has ordered the construction of an extensive network of prisons in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed a decree in 2023 ordering 12 new penal colonies in Donetsk, 7 in Luhansk, 3 in Kherson, and 3 in Zaporizhzhia.

Control of dissent through intimidation, incarceration, and dispossession has always been a blueprint of Russian occupation. Developed initially in the Soviet Union—refined through occupations of Chechnya and the war on Georgia—it has been perfected in Crimea, not least against the Crimean Tatars. Today, it has mutated once again—this time, in newly occupied Ukraine.

Persecution of the Crimean Tatars (Qirimli)

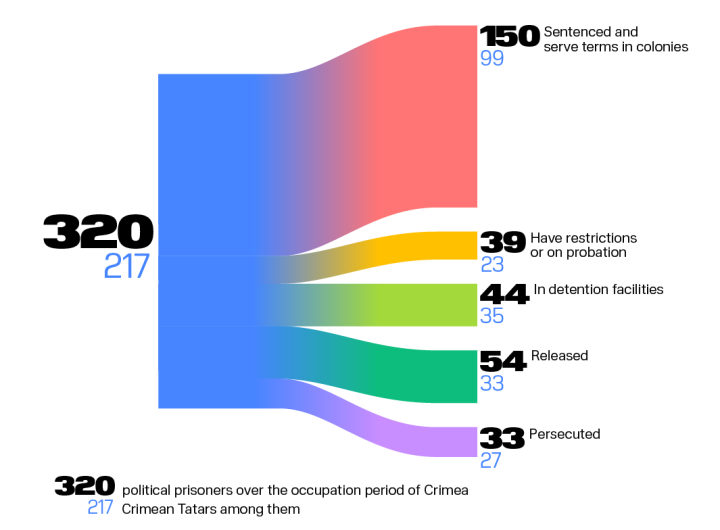

As of 5th of November 2022, the Crimean Tatar Resource Center (CTRC) has documented that out of a total of 320 political prisoners—since the illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia—217 were Crimean Tatars. The CTRC was established in 2015 to “ensure the collective rights of the Crimean Tatars as the indigenous people and the individual rights of all residents of Crimea” and has been documenting violations of those rights since.

Moreover, at that time, 60 deaths and 24 abductees were reported, the majority of which were Crimean Tatars yet again. Throughout the following year, the numbers across the board skyrocketed. The year saw the highest numbers of people detained, arrests made, and violations of the right to a fair trial committed.

The disproportionate level of violence—be it physical, carceral, or judicial—directed towards one of the three indigenous populations of Crimea by the Russian occupational forces has been rooted in centuries of settler colonial narratives and land grabs of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.

This scene from Crimea 5 AM, a play that deals with the intricacies of the life of Crimean political prisoners, is an illustrative microcosm of the eighty years since the Crimean Genocide—the ethnic cleansing through forced deportation of Crimean Tatars into Central Asia, under the decree of Stalin, throughout which up to 100,000 people died.

Scene 1:

(…) This is Veciye Qaşqa. When she was 10, she was deported from Crimea to Uzbekistan on Stalin’s orders. It happened to all Crimean Tatars in 1944.

(…) The year Veciye Qaşqa returned to Crimea was the year a man first landed on the Moon.

(…) Veciye had lived in Crimea when the Soviet Union collapsed, and the other Crimean Tatars returned to the peninsula.

(…) Veciye had lived in Crimea when the peninsula got occupied by the Russian troops in 2014.

(…) Veciye died in Crimea when the Russian occupation enforcement arrested her in Simferopol in 2017. Her heart stopped.

The play ends with the lines from Nariman Dzelial’s statement, published by his lawyer, while he was held under unlawful arrest. Nariman is the first deputy chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, the highest executive-representative body of the Crimean Tatars:

“Don’t let my arrest discourage and frighten you because that is exactly what they are waiting for. Our ancestors proudly carried the sky blue flag with a golden tamga in the past. And we should follow in their footsteps!”

Control of dissent through incarceration

This tactic of control was best outlined by Mumine Salieva, a Crimean human rights activist and founder of “Crimean Childhood,” an organization that cares for and works with the children of political prisoners.

In an interview where she compares the recent mass incarceration and deportation of Crimean Tatars into penal colonies within Russia to the mass dispossession of Crimean Tatar people as part of the Crimean Genocide of 1944, she makes it clear that the repressions within the peninsula are designed to target and make an example of the politically and religiously active population.

Through these deportations the occupation aims to achieve both: prevent dissent by way of intimidation of the general public and export the image of a happy and prosperous Crimea to the rest of the world. For as long as no one is able to tell of the truth and horrors of the occupation, the Russian government can paint the picture they wish.

This is precisely why many have been supporting organizations like Crimean Solidarity, which works under the suffocating Russian settler-colonial rule in hopes of making a difference. Since their formation in 2016, they have served as a support and defense network for political prisoners and their families.

Torture and makeshift carceral infrastructures

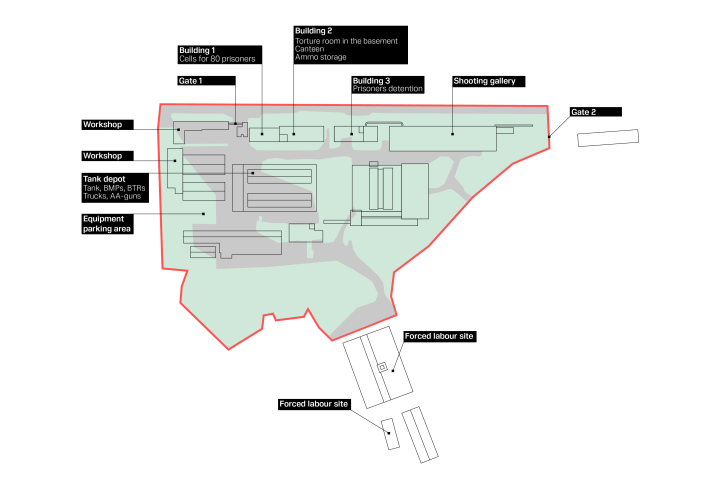

The lack of organized penal colonies and medical prisons on temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine—like the ones it plans to build now—did not stop Russia from detaining, incarcerating, and torturing civilians and prisoners of war alike. On the contrary, their insufficiency has led to hundreds of makeshift carceral facilities being created.

Perhaps the most famous case, before the full-scale invasion, was one of the largest illegal prisons set up on the grounds of what used to be the IZOLYATSIIA cultural center. Once a blooming place for cultural exchanges, exhibitions, lectures, and events, IZOLYATSIIA was turned into a notorious site of torture, imprisonment, and propaganda creation.

Much information is available on the events that transpired there in the ten years since it was converted into a Russian carceral unit, yet throughout the full-scale invasion, such conversions have become the norm under Russian occupation.

Most of the time, unlike IZOLYATSIIA, the converted facilities serve as the space in-between freedom and un-freedom, places where the livelihood and futurity of a detainee are at stake. Used for intimidation, torture, and information gathering, the fields, woods, pits, schools, hospitals, offices, and basements turn into makeshift spaces for the enforcement of the law(lessness).

The Russian makeshift carceral infrastructure under occupation operates in such a way as to displace a detainee continuously, to keep one moving without an ounce of information—to make one feel as if they’re never safe.

In an illustrative case, a civilian woman was repeatedly detained by the Russian occupying forces across the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions. Initially detained in her home on accusations of passing information to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, she was transferred to a Russian military base and held in isolation for two days. The very next day after her release, a different group of the Russian occupying forces arrested her and brought her to a police detention site. She was held in isolation for three days and beaten with a plastic bottle. From there, she was transferred to a makeshift cell and held in isolation for over a month, during which she was tortured and threatened with sexual assault. Upon returning home, she found the Russian occupying forces stationed there having stolen her property for themselves.

On civilians and prisoners of war (POWs)

According to the Center for Civil Liberties, since the full-scale invasion, Russia has deprived 7000 civilians of freedom, 5,400 of which are thought to be illegally placed within Russian penal colonies. Yet these numbers are very optimistic. Dmytro Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, says that since 2014, Russia has detained around 28,000 civilians alone.

The issue of liberating all detainees is complicated. According to international humanitarian law, parties to a conflict can usually only detain combatants—those in the armed forces. They are then called prisoners of war (POWs) and can be held until the end of hostilities but can also be exchanged. Imprisoning noncombatants—in other words, civilians—is illegal, making official POW exchanges more complicated. Civilians are usually less likely to be included in any prisoner exchanges, as one of the main aims of such exchanges is to return combatants.

However, it is crucial to liberate active-duty POWs due to the disproportionate level of violence targeted at them. Russia has subjected Ukrainian prisoners of war to some of the most gruesome war crimes. From being systematically used as human shields to being paraded on the streets of occupied towns in the most dehumanizing fashion. From filmed mock executions and torture to starvation and death.

Yet perhaps there has been no bigger war crime committed than that of the bombing and alighting of the prisoner camp in Olenivka, Donetsk. Over 50 prisoners of war were killed and over 130 injured. Yet, the UN mission to investigate the crime disbanded a few months after the beginning of the investigation as Russia did not allow any access to the crime scene yet again.

The torture and captivity of Azovstal defenders is another known case of inhumane discrimination against prisoners of war, which has been cemented into the collective Ukrainian consciousness. In particular, ‘high profile POWs’ are made an example of by Russia. Maksym Butkevych’s case comes to mind alongside the aforementioned defenders of Mariupol. A Ukrainian anarchist, anti-fascist human rights defender, co-founder of Social Action, and organizer at the No Borders Project, he has been captured and tortured while serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Following a predetermined hearing, he was sentenced to 13 years on fabricated charges of ‘war crimes.’ A charge as ridiculous as the court that carried it out.

In light of such mass dispossession and incarceration of civilian populations and prisoners of war alike, one is reminded of the Russian blueprint for control of dissent, which has been developed in Crimea. Yet perhaps instead of settler colonial ambitions, which no doubt are present in such actions, the main driving force behind these deportations may be of a different nature.

The futurity of Russian carceral infrastructures on Ukrainian land occupied by Russia

“In early November 2022, approximately 1,600 civilian prisoners (all men), who were serving sentences in penal colonies in the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions of Ukraine when the Russian attack against Ukraine began were deported to penal colonies in Krasnodar, Rostov, and Volgograd regions of the Russian Federation,” read a 2023 report from OHCHR. Reports like this are not as rare of an occurrence as it may seem. This could be read as occupying forces ‘making more space’ for the thousands of civilians and prisoners of war illegally detained in makeshift carceral facilities. It may be so, yet a different hypothetical is also possible.

By this point, it is no secret that Russia has been conscripting prisoners across their penal colonies into their fascist war effort. A practice initiated by Wagner PMC in 2022 that has now become standardized. Inmates with particularly long sentences were sought after, as were they to agree to fight and somehow come back alive they would be absolved of their sentences. What this has done to Russian society is already becoming evident, recent reports have shown that in the past year crimes by veterans have grown by 900%, a big part of which are committed by prisoners that were conscripted. Yet what troubles many is what this means and has meant for Crimea and other Ukrainian territories under occupation.

Human Rights Watch says that “since occupying Crimea in 2014, Russian authorities have held 18 unlawful conscription campaigns that disproportionately affected Crimean Tatars, forcing many of them to flee. Between 2014 and 2021, Russia conscripted close to 30,000 Crimean men. Many were sent to serve at military bases in Russia, a practice explicitly prohibited by international humanitarian law.” The Center for Civil Liberties highlighted that through 2019 alone, 18,000 civilians were forcefully conscripted, and as of July 2023, the total number of conscripted Crimean citizens went up to 43,000, disproportionately targeting Crimean Tatar men. Most of such campaigns before the full-scale invasion were targeted at the not yet detained civilian population; usually, men were given the choice to either fight in the occupying forces or be imprisoned for avoiding service. However, more and more reports are pointing to the fact that since 2022, Russia has been using its carceral infrastructures in occupied territories as spaces for forced enlistment into its forces.

In December of 2023, Human Rights Watch spoke with a few Ukrainians held in pre-trial detention in occupied Donetsk on their experience of forced conscription. All three had been illegally detained since before the full-scale invasion and had been tortured continuously for refusing to fight for the occupying forces. They have spoken of hundreds of cases where, due to the torture and propaganda rampant in carceral facilities, civilian detainees were forced to fight, with such efforts being accelerated since September of 2022. For his refusal, one detainee was placed into an overcrowded cell full of prisoners with active tuberculosis; when he complained, the response from the Russian guard was, “If you don’t like the conditions here, going to war is your way out.”

The news of a recently signed decree to build 12 new prisons in temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine points to the possible spread of this practice.

Why send forcefully detained Ukrainians into overcrowded penal colonies in Russia, when they could be held in Ukraine? Why send their soldiers into the meat grinder when they could forcefully do so with a population they intend to cleanse anyway?

The blueprint for control and erasure of dissent under Russian occupation in its current mutation points to the carceral infrastructures becoming the enlistment spaces for the resistance. What we have then is a system that imprisons anyone unwilling to fight against their country, to later attempt to turn them into doing it all the same by way of torture. This is the very bleak reality of occupation, the very tip of the iceberg of the life of all illegally held, detained, and imprisoned across the Russian carceral infrastructures in occupation.

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)