- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Children Under Occupation Continue with Ukrainian Education Despite Dangers

The new school year has begun and despite the immense risk to children, teachers and their families alike, many are continuing with Ukrainian schools online, in secret. Their defiance is in response to the compulsory, indoctrination-style schooling imposed by Russian forces and their collaborators in occupied regions.

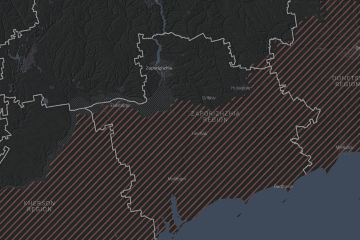

There are 901 schools in the temporarily occupied regions of Ukraine. Many schools have closed, but there are more than 500 schools now operating under Russian control.

Learning under the Ukrainian curriculum is not possible face-to-face while under occupation. Teachers and students who have taken the brave risk to continue have had to move to online learning to keep the children and their families as safe as possible.

Children returned to school on 1 September 2024, and in Russian-occupied regions, are being unlawfully indoctrinated via a new Russian history textbook, a compulsory part of the Russian curriculum.

Russians carry out terror raids of families with school-age children in occupied Kherson oblast. Such aggressive methods to eradicate anything but Russian propaganda-filled ‘schools’ may well be because of continued resistance to Russian occupation.https://t.co/9rxWYohpPP

— Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (@khpg) September 9, 2024

Russia, rewriting history

The Russian curriculum was introduced to schools in temporarily occupied territories in September of 2022. Teachers, students, and parents who refuse to follow it are at risk of violence, arbitrary detention, and ill-treatment.

Occupational authorities have the names and addresses of all the school-aged children in the area. They conduct routine checks of private electronic devices, and if they find content or any traces of online schooling that follow the Ukrainian curriculum, the consequences can be life-threatening.

According to Amnesty International, the new Russian textbook is filled with Russian cliches and propaganda. It tries to vindicate Russia’s illegal invasion by depicting Russia as a victim of a Western plot rather than the aggressor. The textbook contains falsehoods and misrepresents the facts about Russia’s human rights violations against Ukrainians.

“Indoctrination of children at a vulnerable stage of their development is a cynical attempt to eradicate Ukrainian culture, heritage, and identity and is also a violation of the right to education,” Anna Wright, Amnesty International researcher for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, said.

A dictionary and a manual called “Prevention of conflicts, manifestations of extremism and terrorism in a multicultural educational environment” were compiled in 2022 and also introduced to Russian occupied schools. The Russian Ministry of Education gives these to school teachers which they must follow in the classroom.

The dictionary states that words and slogans Ukrainian children might use “containing signs of extremism on nationalist grounds” are "Glory to Ukraine! Glory to heroes!”

Schools in occupied Kherson are now running “cadet classes” with the aim that they will later serve in the Russian army. Russia says that the classes are the “development of patriotic education in the Kherson region. Cadets are known as people of honor, word and true patriots of Russia."

Sources told reporters that the manual states that even discussing “political topics” could lead to what the Kremlin calls, widespread “destructive ideology”. The manual, nor the dictionary, explain in detail what “ideology” or “extremism” is exactly, but simply being Ukrainian fits this narrative.

Imposing Russian education onto Ukrainian children in occupied territories, according to Human Rights Watch “violates the laws of armed conflict, which prohibit an occupying power from making unnecessary changes to laws in the occupied territory, such as Ukraine’s 2017 Law on Education.”

Continuing Ukrainian Schooling despite dangers

Despite the immense risk, Irina Dubas, a Ukrainian school teacher, currently heads the middle school Lyceum No. 3 in Nova Kakhovka, situated in the occupied region of Kherson. Together with other teachers in the school, they continue to teach the Ukrainian curriculum online to families who remain in occupied territory.

In a recent report by Istories, Irina talks about her time teaching Ukrainian under occupation, her captivity, and how families and their children continue to learn even while under threat from Russian occupying forces.

On February 24 2022, when the full-scale invasion began, Irina was in a hospital near Kyiv but she decided to return to Kherson. Kherson was already under occupation by the time she arrived on March 14 2022, but she felt that it was vital to support the children, parents and teachers at her school. Every day they continued to teach lessons, remotely. While Irina herself stayed inside the school.

The new “Kakhovka head” Vladimir Leontyev, was appointed by Russian authorities. He ordered that schools continue, but under the new Russian curriculum—which Irina refused. Leontyev has Ukrainian citizenship and is registered in Kyiv but collaborated with Russian authorities during the first few days of the full-scale invasion.

When the occupation began, Vyacheslav Reznikov, previously a well-respected Ukrainian school director, collaborated with Russian forces and now heads the occupation's education department. He paid Irina a visit, along with three Russian machine gunners. “Such unfortunate boys, their machine guns were bigger than themselves,” she said.

“The machine gunners stood behind me. Reznikov started to say, ‘Don’t refuse, Irina, everything is so good with you. You are so advanced. Our guys have almost taken Mykolaiv and Odesa. There is nowhere to go. And we need to do education. Other directors will follow you.’ He gave me two weeks to think about it. But I wasn’t even going to think about it. I didn’t want to go to any kind of Russia. I believed in victory and was preparing to defend my school to the last,” Irina recalled.

Irina continued teaching using the Ukrainian curriculum. Then, her school was raided, and on August 18, 2022, Irina was taken prisoner. She was held captive for five days and threatened with electric shocks, which she knew that other women were being subjected to also.

She managed to evacuate to Kyiv, where, for the first time since the full-scale invasion, she cried. The psychological impact and emotions from her captivity, she says, will never subside.

"I couldn't betray my school. I realized that if I could survive life under occupation and captivity, then I could do anything in the world," says Irina.

I dropped by a small exhibition about 🇷🇺 occupation of #Kherson. Most striking exhibits were the propaganda for children. Textbooks, school bags, even games all aimed at brainwashing Ukrainian identity out of young people. pic.twitter.com/KD9mpSDwHb

— Dame Melinda Simmons (@MelSimmonsFCDO) January 16, 2023

Less than a week later, Irina had already found new teachers and students to continue studying the Ukrainian curriculum online. 647 new students had enrolled for the school, most of which were still under occupation. Irina had managed to enroll more children than were enrolled before the full-scale invasion, which had 637 children studying there.

For safety reasons, teachers were based abroad or in Ukrainian territory. Despite the dangers, families had to manage their own safety measures.

Many families hid their children's work on hard drives, and some moved to small villages and in the countryside where there were less raids by authorities. Many children learn in the evenings to not raise suspicion, as Russian education is compulsory and failure to attend schools leads to house raids. Another teacher, Anna, from temporarily occupied Melitopol, also continued to teach the Ukrainian curriculum and spoke to Istories. "It's a great act of heroism to continue studying in a Ukrainian school while under occupation," said Anna. "In Melitopol, people rat on each other in a very dirty way.” She said that during the first few weeks of occupation, she saw Ukrainian students walking around in T-shirts and caps with the Russian coat of arms on.

At the start of Melitopol’s occupation, Anna and her daughter routinely protested against it and were not quiet about their pro-Ukrainian position. She told her students to stay as quiet as possible for their safety. Over time, threats became more persistent. Even receiving notes from acquaintances that read "burn in hell, Ukrainian scumbags.”

Pro-Ukrainian activists were being kidnapped, killed and sent "to the basements" so Anna and her daughter fled to Ukrainian territory. There, she continued teaching online to students in Melitopol and Zelenskyy awarded her the National Legend of Ukraine award.

Unfortunately, due to the increasing fear of reprisal, Anna was not able to recruit any more families for the 2024 to 2025 school year.

“It is becoming increasingly difficult to hide: phones are tapped, parents with children can be searched at any moment on the street and their phones can be checked. Flash drives with lessons are hidden in the most secluded corners of houses.”

In Nova Kakhovka however, Irina has again managed to enroll more students than before the full-scale invasion for this school year but refuses to specify exact figures in fear of exposing families to danger.Irina ensures her teachers pursue not only teaching, but have what, “the war took from them, laughter and joy." The school ensures that grades are not of most importance, but their mental wellbeing, as fear of reprisal could cause immense stress and anxiety.

Some former students from the class of 2021 are in the military defending Ukraine, and others are being held captive by Russian forces.

Punished for Ukrainian schooling

Amnesty International has also shared recent stories of families who defied Russian authorities and continued to learn under the Ukrainian curriculum. Names have been changed for safety reasons.

Yuriy,* a father of three who is from a village near Nova Kakhovka (he requested not to name the village), said that after Russia’s full-scale invasion, his daughter switched to studying the Ukrainian curriculum online.

In October 2022, Yuriy was visited by a Russian official then was arbitrarily detained for six days by Russian authorities as he wouldn’t put his child in a Russian school. “They only beat me one day. They fed us, but not very well. They also wanted us to sing the (Russian) national anthem,” he said.

Mariya,* from Nova Kakhovka, left Russian occupied Kherson in September 2022. Russian soldiers kicked her daughter’s phone from her daughter’s hands when it played a song in Ukrainian as a ringtone.

This is a school. The are 800 students who study there now. Online. But before the war there were only 200 students. What happened? This village was not occupied. And it is closest to Kherson, which was. The law did not allow operating the schools in the occupied territories 1/ pic.twitter.com/PB081Rrfe4

— Tymofiy Mylovanov (@Mylovanov) April 2, 2023

Russian collaborators in the educational system, Kherson

While thousands of children, families, and teachers are resisting the forced implementation of the Russian world while under occupation, some—like Reznikov and Leontyev—are working directly with occupation authorities within the educational system. Without so-called traitors working with the Russian occupiers, establishing this new indoctrinated education system would be extremely difficult for Russian forces.

Researchers at Evocation who work specifically to expose collaborators say that they should be held accountable for their contribution to the illegal invasion of Ukraine. Evocation has found evidence of 2647 collaborators working across a variety of regions in Ukraine.

Before the full-scale invasion, there were more than 100 pro-Russian organizations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, many of which, according to reports, were hubs for collaborators engaged in spying and bribing local elites.

One case was of Tetiana Kuzmich, head of the "Rusych Russian National Community,” an NGO working in Kherson, Mykolaiv, and Odesa regions. She was arrested for treason and suspected of spying for Russia.

In October 2020, she was released on bail for half a million hryvnias, around $12,000 USD. At the same time, she had access to schools in Kherson and worked as a senior lecturer at the Kherson Academy of Continuing Education.

When the full-scale invasion began, she became one of the key figures in Russia’s takeover of Kherson Ukrainian education system. In July of this year, 2024, she represented occupied Kherson at the “Russia World” forum held in Sevastopol, Crimea.

In her speech, she said that her aim is to “return Russianness to those Ukrainians who today remained on the other side,” which is “one of the aspects of the denazification of Ukraine.”

Collaborators like Kuzmich were able to easily reappoint collaborators and invaders from Russian territory to certain positions within the education system, allowing them to take over schools quickly.

Vladimir Saldo has rich political experience in Kherson council, including previously being appointed as Kherson mayor to the People’s Deputy of Ukraine.

By March 2022, after the full-scale invasion began, the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine suspected him and others of having ties to the Russian Federation and banned his activities. He then began to integrate the Kherson region into the Russian federation.

This week, he reported that lectures were taking place within schools in occupied Kherson to celebrate Russia’s state media. Children learned about the “peculiarities of journalists' work in the modern world and about “fakes.”

Saldo wrote on the Russian Government of Kherson’s website, "for our region, "Conversations about the Important" are of particular importance, since for 30 years Ukraine has been brainwashing children with false ideas and values. Now we need to make sure that the children firmly associate themselves with Russia".

There are many more cases where teachers have taken a stand against Russian authorities. Iryna Radetska, the deputy principal of Preparatory High School No. 6, refused to adopt the Russian education system.

She told Pravda that she disguised herself as a mother wanting to enroll her child. However, when entering the school office she told them that she had a grenade in her bag and intended on detonating it. Days after the incident Russian forced took her to temporary detention center on Teploenerhetykiv Street and was placed in a torture chambre for those who resisted Russian rule.

Iryna was subjected to violent beatings and endured torture with electricity and water. "It was a conscious decision. Perhaps I didn’t fully understand the consequences, but I just love my Ukraine. I wanted to show that we are not afraid of anyone, that we have not surrendered. I wanted them to know that they are here temporarily," Radetska told Pravda.

It’s clear that the fight for Ukraine’s freedom is not only through military action. Children, their families and teachers are fighting their own frontline, against all odds, for a peaceful and Russian free Ukraine.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)