- Category

- War in Ukraine

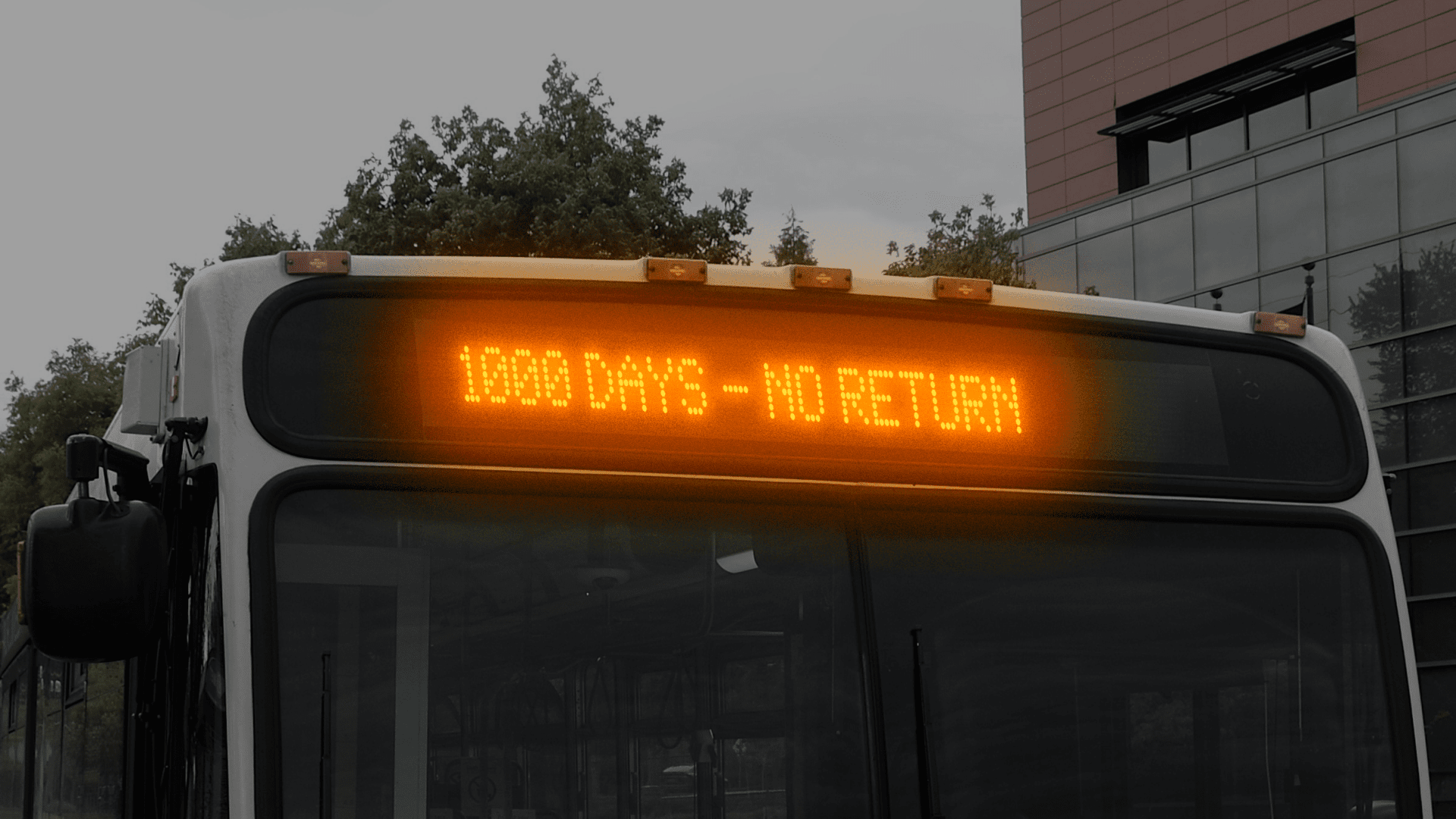

How 1,000 Days of War Reshaped Ukrainian Society

November 19th, 2024 marks the 1000th day of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a devastating milestone that has reshaped the nation and crossed the point of no return. Families shattered, cities ruined, and identities forever changed. The life that was is gone.

It’s an autumn morning in Kyiv, the nation's capital. An overcast sky, likely to persist until spring, casts a grayish lull over the city. The sounds of air raid alarms, air defense systems, and the interception of Russian missiles and drones have become a constant presence—semi-permanent consequences of the war.

While the weather will eventually change, the air threats are expected to endure much longer, becoming an inescapable part of daily life. For many in Kyiv, these threats have become almost routine. The instinct to rush to a shelter has faded; now, more people simply wait it out, either in the bathroom or, in some cases, opting to ignore the danger and get some much-needed rest before the workday begins.

At the dinner table, conversations often revolve around learning how to properly apply a tourniquet, which neighborhood was recently struck, or the growing readiness for mobilization among the millions of men aged 25-60.

Though it may seem that the people of Kyiv have become accustomed to Russia’s air attacks, the harsh reality remains that civilians across the country are dying daily from these assaults. Bad news has become a daily constant, one that people now consume and process like a bitter tonic.

Now, on the 1000th day of the war, this grim reality has become routine for many. Waking up, scrolling through news outlets, checking on loved ones near the frontline, and monitoring the shifting frontlines themselves—this is the rhythm of life.

In the early days of the war, shock was just the precursor to the deep spiritual and personal transformations that swept across the nation, unfolding alongside Russia’s rapid invasion.

The war and its consequences have reshaped how Ukrainians think, interact, and live. Over time, people have faced varying degrees of exposure to the brutal realities of life in a nation embroiled in an existential struggle. Much has been altered; new realities were forced upon millions.

At this reluctant milestone of 1000 days, Ukrainians reflect on how radically their lives have changed. Yet, it raises an important question: Have they passed the point of no return? Is it even possible to return to the lives they once knew before the war?

If it hadn't been for the war

Over the past 1000 days, Kyiv has become a central hub for internally displaced people (IDPs) seeking safety, economic opportunities, and a chance to rebuild their lives. A tenth of Ukraine’s 3.7 million displaced now live in the capital, pushing its population back to pre-war levels.

Once filled with familiar faces, the streets have undergone a profound shift. In the early days of the Russian full-scale invasion, many residents left the city—some heading to the frontline, others fleeing westward or seeking safety abroad.

In their place, Kyiv became home to people from the east and south. Once rare, Donetsk and Luhansk license plates are now a common sight, as displaced people from these regions settle in the capital.

Many from the south, like Yulia Danilevska, an artist from Kherson, have also sought refuge in Kyiv, bringing their stories of occupation, survival, and the eventual search for safety.

Yulia remembers the early days of the war when she refused to leave Kherson despite the Russian occupation. "In those first days, no Ukrainian city felt safe, and I didn’t want to leave my husband," she explains. Although relatives in Poland offered refuge, Yulia stayed behind, quietly documenting life under occupation.

“It was a wild experience,” she reflects. “You can never fully understand what it’s like to live surrounded by enemy soldiers.” As the occupation dragged on, many of Yulia's friends and fellow activists fled, but she remained, knowing that her role as an artist was to witness and document the reality around her. "I painted quietly, focusing on the everyday life in occupation, on the horrors we were enduring," she says.

However, the constant shelling and the lack of communication from the outside world wore on her. "We were constantly waiting for liberation, hoping for Western support, but months passed with no clear end in sight."

Eventually, the unbearable conditions forced her to leave, though she didn’t go far. Yulia moved to nearby Mykolaiv, wanting to remain close to home in case something happened to her parents. "I wanted to be able to return quickly if needed," she explains.

Now, in a safer place, Yulia reflects on the emotional toll of those months. “In stressful situations, you activate your resources to survive, and you do what you have to do,” she says. The months of living under occupation have left their mark, and Yulia admits she now sees signs of PTSD.

"I’m in a relatively safe place now, but I still see signs of trauma. You do what you have to do to be useful." Like so many others, Yulia’s life has been irrevocably changed by the war. The person she was before the war feels distant now, shaped by the survival instincts she had to rely on in Kherson and the harsh lessons of occupation.

Many in Ukraine are at risk of developing PTSD, which experts estimate to affect up to a fifth of the population. Outside of full diagnosis, many more experience the various related symptoms caused by prolonged exposure to trauma and violence.

A change of course

As Kherson was liberated in late 2022, the Ukrainian counteroffensive brought a momentary sense of hope. However, as the war dragged on, the reality of continued occupation in some regions and the ongoing battles made it clear that victory was still elusive.

The war itself has forced an entire generation of Ukrainians to rethink their lives and careers. Ordinary citizens, many of whom never considered military service, now find themselves on the frontlines, defending their homeland.

Family men, entrepreneurs, teachers, and workers—people whose daily lives once revolved around jobs, families, and peaceful routines—have become the backbone of Ukraine's resistance.

With Russia's advance threatening the very existence of their country, these men and women have answered the call. Some volunteered at the outset of the war, while others came to realize that the responsibility would eventually fall on their shoulders.

Yaroslav Rudakov, a Kyiv-based entrepreneur, never imagined he’d join the military. A successful cosmetics business owner, he was planning on expanding the “White Sprut” brand, until the war forced him to reconsider. “If it hadn’t been for the war, I wouldn’t have thought about a career in the military,” he says. But a year ago, he decided to enlist.

Now, balancing his military duties with remotely managing his business, Yaroslav reflects on how the war has changed him. “My life completely changed that day, and it continues to change,” he shares. “I’ve become more responsible and consistent.” The war has accelerated his personal growth, pushing him to take on responsibilities he never imagined.

“It’s difficult to leave home, your wife, and loved ones, but if you don’t take responsibility, it wouldn’t make sense to expect someone else to do it,” he adds. Like many Ukrainians, Yaroslav now faces the weight of duty, knowing that the only way forward is to act.

Looking ahead, he believes the lessons learned during the war will continue to matter after it ends. “Winning a battle is only part of the struggle. Afterward, we’ll face new challenges together, and we need to stick together, not argue. This is a lesson our nation has been learning for centuries.”

Since 2022, Yaroslav has balanced his business with volunteer work, and by early 2024, it became clear that Ukraine needed more experienced soldiers. He joined the Armed Forces while still managing his business remotely. “If I don’t take responsibility, I can’t expect anyone else to. This is the reality we face,” he concludes.

Language as identity

As Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv has long attracted people from across the region, including former Soviet states. The Russian language was once tolerated in everyday conversations as a practical means of communication with non-Ukrainian speakers.

Many Ukrainians used it simply for convenience, yet after the invasion of 2022, the situation shifted almost overnight. The Russian language quickly became synonymous with the aggressor.

On the streets, in cafes, and in homes, people reverted to speaking Ukrainian—no longer out of formality but out of necessity. This change, once subtle, has deepened over the past thousand days, reshaping not only how Ukrainians communicate but also how they see themselves and their country.

Maryna Kulakova, who left Kyiv to seek safety in Western Ukraine near the Slovakian border when the war began, eventually spent two years as a refugee in the United Kingdom. Upon returning to Kyiv, she noticed the transformation the city had undergone. She explains:

“I spent two years abroad, and hearing the Russian language on the streets in Europe made me feel threatened and triggered, as there were so many instances of Russians attacking Ukrainian refugees in Europe. Now for me, it just serves as a symbol of Russian colonialism in the purest form. I can’t separate it from violence towards Ukraine on any level. This is the language the aggressor speaks, and I hope to forget it one day completely.”

Our shared past

The war has torn families apart in ways unimaginable to many. One man, who wishes to remain anonymous, reflects on the painful rift with his twin brother, with whom he had always been close.

"We were born on the same day and always shared everything," he says. "When the war started, my brother’s flight back to Kyiv was rerouted to Poland. From there, he moved to Romania, closer to our family in Chernivtsi. We were so close, but since then, I haven’t seen him."

The emotional strain deepened when he learned that his cousin, once a childhood companion, now serves in the Russian Space Forces, launching missiles at Ukraine—the very land where they had once played together. "He tried to contact me and even apologized, but I suspect his life in Moscow means more to him than our shared past."

The pain of this betrayal has left deep scars, making the possibility of reconciliation seem impossible. "The war hasn’t just divided us geographically but ideologically," he reflects. The betrayal, both personal and ideological, has led him to a painful conclusion.

"My life was going well before the war, but now it feels like wasted time—time I can never get back." As he approaches his 40s, the weight of loneliness and the loss of his former life presses heavily on him. "I’m alone now—my friends are either fighting, abroad, or dead," he says. "Instead of building a future, I’m left with years that feel lost."

Looking to the future

Ten years ago, with the start of the Revolution of Dignity, Ukraine began its journey toward a European identity. At that time, few would have believed that a war between Ukraine and Russia could become a reality, let alone last this long. Today, Russia continues its efforts to extend its influence over its neighbors and beyond, with some success, bolstered by propaganda and pro-Russian parties.

In Ukraine, however, this seems to be a thing of the past. The destruction of buildings in Kyiv, including a children's hospital hit by cruise missiles, the endless power outages, the relentless news cycles over the past three years, and the countless personal losses have irrevocably changed the people of Ukraine. For them, the point of no return in relations with Russia was crossed long ago.

When asked about the prospect of forgiveness for the Russians, Yulia’s response is blunt: "I don’t think it will ever happen, at least not until the last witnesses of this war are gone. Perhaps 50 to 100 years from now, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will forgive them. In the distant future, our suffering and the crimes of the Russians will simply become historical facts."

However, Yulia emphasizes that the real issue lies with the majority of Russians, who do not seek forgiveness from Ukraine. "The 'buffer zone' should not be on the land, but in the relationships between us and the Russians," she asserts.

UNITED24 is raising funds to rebuild Ukraine. Donate now to help restore homes, lives, and hope.

-9377b86f9f8cd8a2b08f20ffd5f043e0.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-5568db4fb3d8644b8f1bf8244594bec1.png)