- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Ukraine’s Historic Path to Independence, Defying Both Moscow and Global Pressure

Moscow was determined to keep Ukraine under its control, refusing to grant independence. But Ukrainians had a different plan—and they were ready to make it happen.

On August 24, 1991, Ukraine declared its independence. Later that year, on December 1, a nationwide referendum confirmed this decision, with more than 50% of votes in favor in every region, including Crimea. However, the path to this point was far from easy, and even in the final moments, Moscow did everything possible to prevent it.

The Late 1980s

The Soviet empire was falling apart. The Warsaw Pact, Moscow’s counter to NATO and its influence in Europe, disintegrated: the Berlin Wall fell, Germany reunified, and Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia embarked on market reforms. The Baltic nations—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—were confidently moving toward independence. Ukraine also declared its sovereignty.

Despite these pro-freedom sentiments, the dissolution of the Soviet Union was not openly discussed, and Western leaders were particularly averse to the idea. Mikhail Gorbachev, who had engaged in dialogue with Western countries and even received the Nobel Peace Prize, was a familiar and accepted figure to the political leaders of the world’s major nations. They supported the liberalization of the Soviet Union but feared its collapse. Why? Because of the nuclear arsenal spread across different Soviet republics and the massive Soviet army. The disintegration of the USSR could lead to chaos in this region, with potentially unpredictable consequences.

1991

When U.S. President George H.W. Bush visited Kyiv in July 1991, he supported preserving the union in some form. According to CIA intelligence, Ukraine could not achieve independence peacefully, so in his Kyiv speech, Bush expressed support for Gorbachev and the New Union Treaty. Speaking in the Ukrainian parliament, Bush warned against "suicidal nationalism," which he contrasted with the "freedom" that could supposedly be achieved within the Soviet model. It was clear: the United States did not support Ukraine’s quest for independence. This speech would later be called the "Chicken Kiev Speech" in the U.S.

Gorbachev’s and Bush’s plans were undermined by internal divisions within Moscow itself. On the morning of August 19, a coup led to the creation of the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP), or simply—the Gang of Eight. Chaos ensued in Moscow, with troops deployed and the White House—the Russian government building—coming under fire. Moscow became preoccupied with solving its internal problems.

Ukraine seized this opportunity. The signing of the New Union Treaty was scheduled for August 20, but due to the coup in Moscow, it never happened.

On August 23, Leonid Kravchuk, Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament), traveled to Moscow for a meeting with Gorbachev and other republican leaders, where he witnessed the visible weakening of the central Soviet authority. Kravchuk returned to Kyiv with the realization that Ukraine could indeed become independent. It’s important to remember that each republic formally had the right to peacefully secede from the USSR.

August 24, 1991

On the morning of August 24, crowds gathered outside the Verkhovna Rada building in Kyiv, demanding change.

The parliamentary session was set to adopt several documents aimed at strengthening Ukraine’s political sovereignty. Kravchuk persuaded the communist majority to vote for laws proposed by the national democrats (The People's Movement of Ukraine), including one on the status of military forces on Ukrainian territory. Meanwhile, the national democrats, led by academician Ihor Yukhnovsky, began pushing for independence. Writer Volodymyr Yavorivsky read a brief text titled "Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine," demanding it be put to a vote. The main author of the declaration was Levko Lukianenko, head of the Ukrainian Republican Party, a long-time political prisoner, and a leader of the dissident movement.

Everything moved quickly to prevent external forces from intervening.

The communist-majority parliament was in disarray. It’s worth noting that 375 out of 450 MPs—a clear majority—were communists. Traditional opponents of independence were in a difficult position. Gone were the days when the communist majority in parliament was a unified force. Kravchuk and some communists supported sovereignty and even independence, believing that this would free them from having to look to Moscow. The leader of the communist majority, Stanislav Hurenko, urged his fellow party members to support the declaration to avoid problems for both themselves and the party. Even the communists understood that Moscow’s attention was elsewhere.

Those who still hesitated dropped their doubts when the opposition offered a compromise: independence would be confirmed by a referendum on December 1, to be held simultaneously with the presidential election. Many saw this as an ideal solution: voting for independence guaranteed them protection in the present, while the referendum was postponed to a future date, leaving its outcome uncertain. So the communists supported the Independence project.

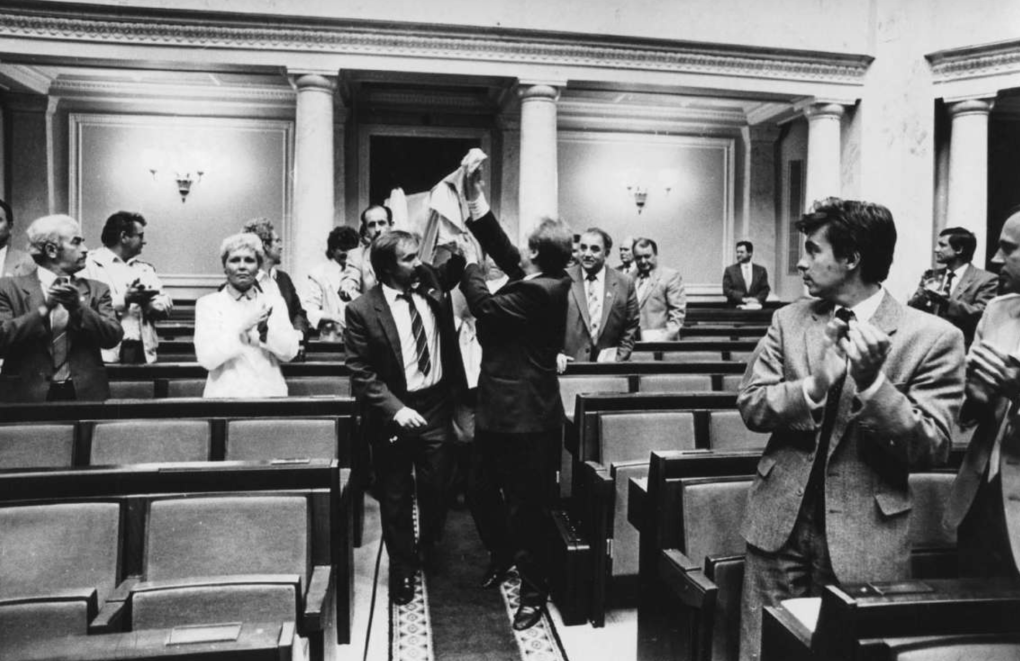

The results were announced At 5:57 p.m. on August 24, the hall erupted in applause, and MPs leaped from their seats, embracing each other. The Ukrainian parliament chose independence: 346 voted in favor, 1 against, and 3 abstained. The crowd outside cheered loudly.

December 1991

The following three months were challenging for Ukraine. Moscow, having regained its footing after the events of August, was unwilling to let Ukraine go. A race began: the Ukrainian elite campaigned for citizens to support independence in the December 1, 1991 referendum, while Russian forces spread narratives about the negative consequences of such a choice. Meanwhile, Moscow attempted to create another union in some form to maintain control over Ukraine. Proposals included keeping control of air defense and aviation in Moscow or controlling the borders, among other formats. Finally, Moscow even proposed a new alliance called the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). But Ukraine ultimately did not ratify it.

In December 1991, Ukraine confirmed its independence in a referendum, elected its first president, established its armed forces on December 6, and on December 8, 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist with the signing of the Belovezha Accords. Other republics had also supported this idea by the end of the month.

Ukraine’s independence never sat well with Moscow. In 1992-1993, they attempted to destabilize the situation in Crimea and seize control of it. In the mid-1990s, they spread anti-Ukrainian sentiments in Eastern Ukraine. In 1995, Kremlin elites began promoting the narrative that the Belovezha Accords were a criminal act. In 2003, there was the Tuzla Island conflict, followed by gas blackmail in 2005.

In 2014, Russia began its war against Ukraine. Later, the Kremlin propagated the narrative that Ukraine doesn’t exist. The struggle for independence continues.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)