- Category

- War in Ukraine

Azov Fighters Have Been Held In Russian Captivity for Over Two Years as Putin’s Propaganda Trophies

Two years after the fall of Azovstal, the fate of hundreds of Ukrainian prisoners of war, including members of the Azov brigade, remains uncertain. Held by Russia in undisclosed locations, they are denied contact with families, exchanges, and access to international observers. Why?

The Ukrainian city of Mariupol suffered a brutal fate at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Surrounded by Russian forces, the city’s remaining civilians and military personnel defended it for two grueling months. Outnumbered and outgunned, the Ukrainian forces were eventually pushed into the Azovstal steel plant, the city’s largest industrial complex.

Among those who held the line at Mariupol were soldiers from the Azov brigade, one of Ukraine’s most prominent and combat-read military units. The Azov brigade has been shrouded in myths, often fueled by Russian misinformation campaigns aimed at distorting its true nature. We have meticulously examined and debunked myths about the Azov Brigade.

In late May 2022, the civilians and military personnel taking refuge at Azovstal voluntarily surrendered, including Azov soldiers, becoming Russia’s prisoners of war. The act of surrender is governed by the Geneva Conventions, an international legal framework outlining the treatment and exchange of prisoners of war. However, it is this aspect that has been so blatantly disregarded by Russia.

Red Cross

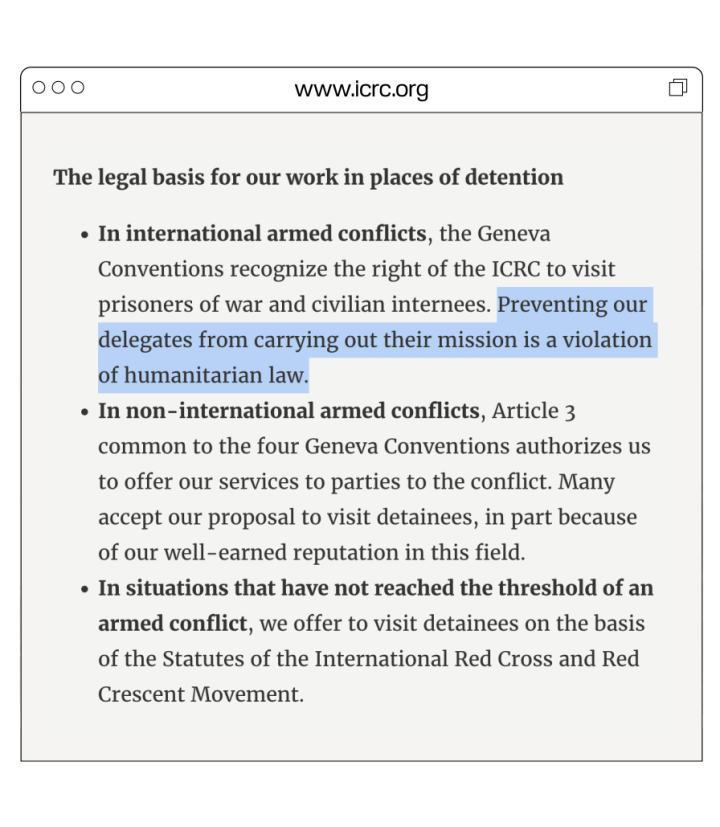

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) acts as a mediator in matters concerning prisoners of war. It is crucial to distinguish the ICRC from local branches of the Red Cross. The ICRC possesses a mandate that empowers it to monitor the treatment and conditions of prisoners of war in each warring nation.

The war in Ukraine has exposed the glaring imperfections of international treaties. Since 2022, Russia has barred ICRC representatives from accessing Ukrainian prisoner-of-war detention sites. In contrast, Ukraine grants full access to all international human rights organizations, including the ICRC, and journalists from reputable international publications (1 / 2 / 3). While stories about the treatment of Russian prisoners in Ukraine are readily available, there is a void of information regarding the fate of Ukrainian prisoners held by Russia.

The ICRC acknowledges Russia’s obstruction of their access and their inability to conduct independent assessments of detention conditions. Despite these obstacles, opportunities for progress exist. In 2022, ICRC President Peter Maurer met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, demonstrating the potential for dialogue. However, the ICRC has failed to leverage this potential, neglecting to apply sufficient international pressure on Russia to initiate dialogue and permit inspections.

“The ICRC has not released a statement on the infringements on international law made by Russia. This is true even in connection with the refusal of the Red Cross representatives to visit the place of detention of POWs in Olenivka, which is definitely provided for by the Geneva conventions,” says Zahar Tropin, a professor of law at the University of Kyiv.

In an interview with UNITED24 Media, Azov staff officer Illia Samoilenko, call sign Gandalf, revealed that during his time in Russian captivity following the siege of Mariupol, he never encountered any representatives of the Red Cross. Watch the full interview below.

The ICRC’s inaction is a dereliction of duty, as they are the only organization with an internationally recognized mandate to inspect the conditions of prisoners of war. Their failure to fulfill this role undermines the legitimacy of both the organization and the treaties it is meant to uphold. This inaction is particularly egregious in light of a UN report based on data collected in 2023-2024, which reveals that Russia has executed at least 32 Ukrainian prisoners, and of the 60 interviewed prisoners who returned to Ukraine, 39 reported experiencing sexual violence or torture.

The ICRC’s complacency in the face of such grave human rights abuses raises serious questions about its commitment to its mission and its effectiveness as a humanitarian organization.

Azov

The Azov brigade’s situation is particularly dire. Ukraine has conducted 51 prisoner exchanges since the full-scale invasion began, resulting in the release of over 3,000 Ukrainian soldiers. However, only a small fraction of those released are Azov fighters.

Currently, approximately 900 Azov fighters remain in captivity, with Russia refusing to exchange them. This refusal, while not officially articulated by Russia, is widely understood as a cynical tactic to exploit their symbolic value and inflict psychological harm on the Ukrainian people. Russia’s refusal to exchange Azov prisoners is widely viewed as a calculated move to exploit propaganda. Putin’s regime has consistently demonized Azov, falsely portraying them as neo-Nazis to justify the invasion of Ukraine and garner domestic support for the war. By holding Azov soldiers captive, Putin can perpetuate this narrative, painting them as dangerous extremists who must be isolated and punished, thereby pushing into overdrive the “denazification” narrative that underpins his aggression against Ukraine.

Russia’s actions extend beyond restricting the exchange of Azov soldiers. They also withhold information about their location and conditions. Over 1,600 defenders of Azovstal have been captive for more than two years, with no information available about their whereabouts or well-being. There is no contact with them, and representatives of international human rights organizations and the ICRC are denied access.

Such denial of access to prisoners of war and lack of communication are grave violations of international humanitarian law, including the Geneva Conventions, which mandate the humane treatment of prisoners and the right to communicate with their families and humanitarian organizations.

Exchange

Russia has consistently obstructed the prisoner exchange process throughout the full-scale invasion. For example, in the second half of 2023, exchanges were suspended for over four months, despite Ukraine’s readiness to proceed at any time, even with the involvement of the international community, including Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, or Qatar.

Russia’s motives are clear: they use prisoner exchanges as leverage to pressure Ukraine and destabilize the country. Dmytro Lubinets, the Verkhovna Rada Commissioner for Human Rights, suggests that Russia aims to portray Ukraine as the party unwilling to engage in exchanges, thereby inciting public discontent.

However, Ukraine is eager to proceed with exchanges. In preparation for the joint Swiss-Ukrainian Peace Summit on June 15-16, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy emphasized Ukraine’s readiness for an “all for all” exchange. The rest is now up to Russia.

Questions

The silence from the Red Cross and the broader international community raises questions. Why has the world turned a blind eye to Russia’s blatant disregard for international humanitarian law? Is it mere apathy, political expediency, or an acceptance of a new norm where human rights mean nothing?

Putin clearly views the Azov soldiers not as prisoners of war, but as trophies—bargaining chips to sow discord within Ukraine and propaganda tools in his “denazification” narrative outside of it. This tactic not only inflicts immense suffering on the captives and their families but also gravely undermines international law and the very principles of human dignity.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-5adb65e550f9dec24a01a35019e4b6b5.jpg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)