- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Russia’s Shadow Fleet Continues Supplying Oil to the EU Despite Sanctions

A closer look at just two European ports reveals how Russia’s shadow fleet bypasses sanctions to deliver crude oil to the European Union—raking in billions in the process.

The EU remains a buyer of Russian oil and gas, though the origin of the oil often goes unmarked. Facilitated by a shadow fleet and sanction-evading schemes, including ship-to-ship oil transfers at sea, Russian oil finds its way to European markets. Journalists from Ukrainska Pravda investigated several such cases happening in the Black Sea in just one week, focusing on two ports in Bulgaria and Romania—both EU and NATO members. How does this operation work?

Novorossiysk, Russia

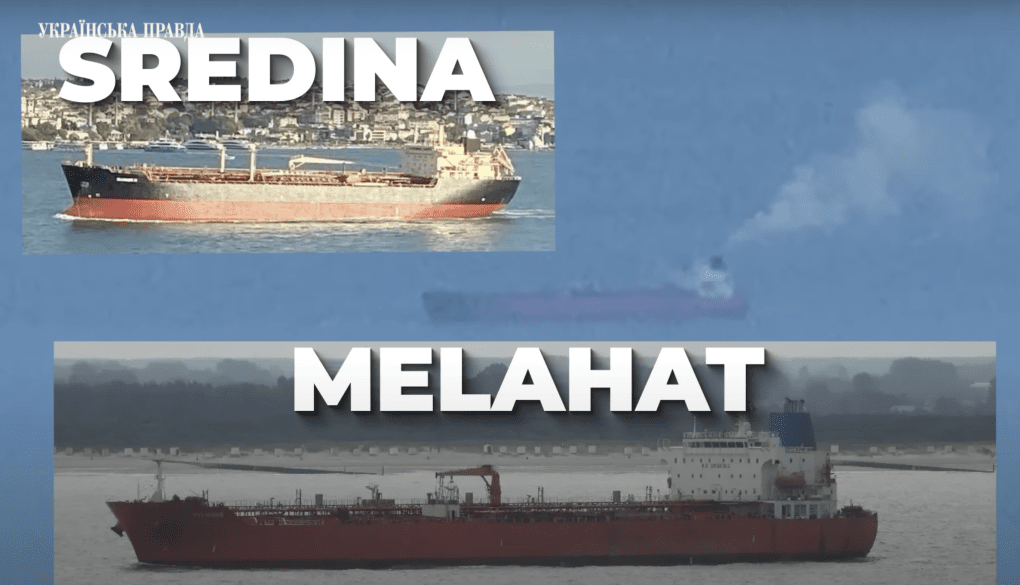

The loading of oil tankers for delivery to the European Union begins in Novorossiysk, a Russian port city. For example, two tankers—the Lipari and Sredina, flagged in Liberia and Panama, respectively—departed from Novorossiysk on November 8 and 9, 2024.

Burgas, Bulgaria

A few days later, the Lipari arrived in Burgas, Bulgaria. Nearby is Rosenets, one of Bulgaria’s largest oil terminals, previously owned by Lukoil.

Journalists observed the Stamos tanker (registered in Malta) approaching the Lipari at sea and beginning a ship-to-ship oil transfer. The process took about a day. Following the transfer, the Stamos delivered the Russian oil to the refinery, filling its storage tanks with crude.

In 2023 alone, this refinery processed 5 million tons of Russian oil in the first ten months, contributing over $1 billion in direct tax revenue to Russia. While the Bulgarian government committed to reducing Russian oil imports in 2023 and ending processing entirely by October 2024, the journalists documented the continued delivery of Russian oil in mid-November 2024.

Constanța, Romania

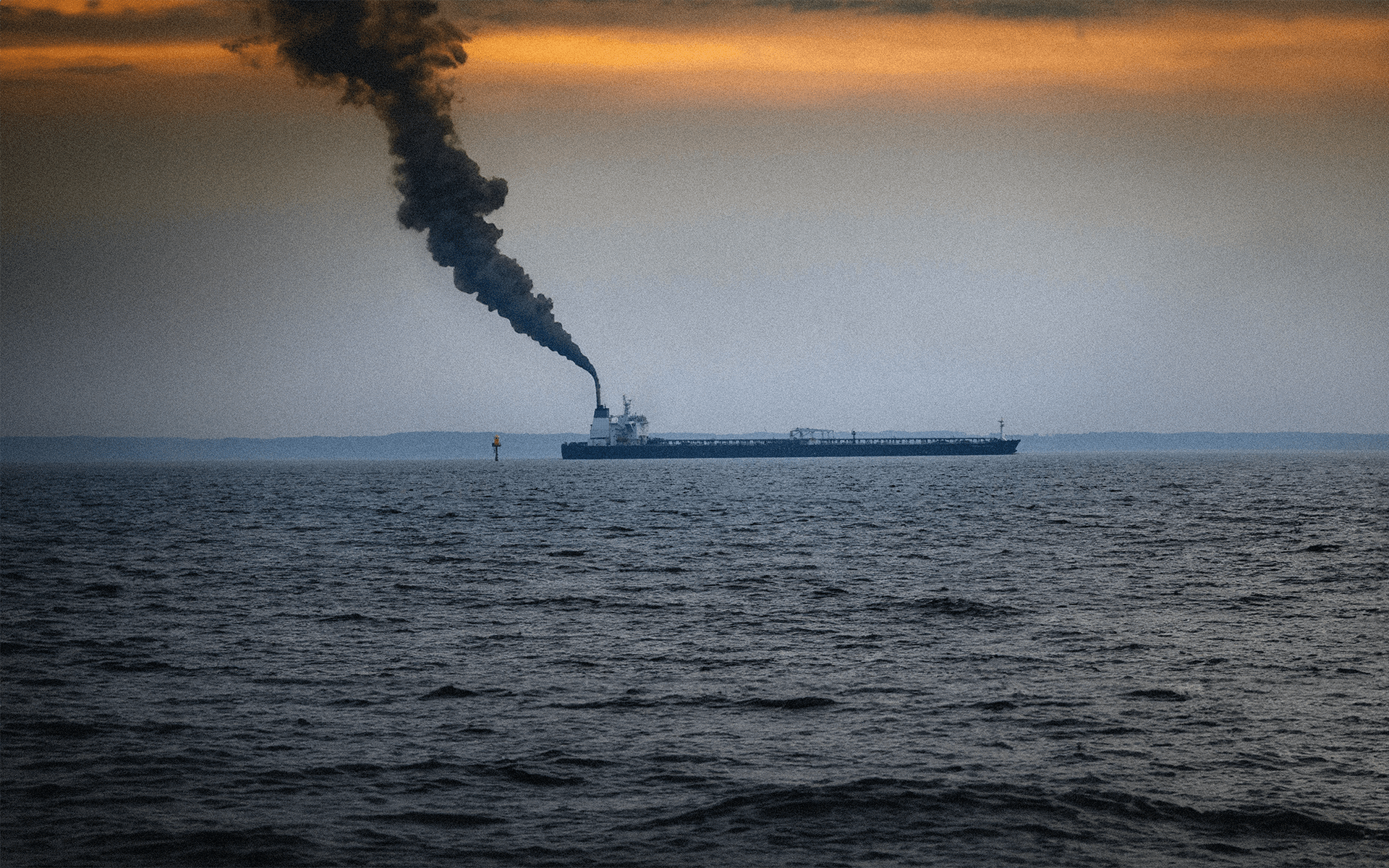

The Sredina tanker made its way to Constanța, Romania, where it remained for several days before journalists documented a similar operation to the one in Bulgaria.

At night, with the assistance of tugboats, the Sredina docked alongside another tanker, the Melahat (registered in Panama). A ship-to-ship transfer began, lasting through the night and into the next day. Afterward, the Sredina returned to Novorossiysk, while the Melahat, now carrying Russian oil, departed for another European port.

Journalists later documented yet another tanker, the Altai, registered in the Marshall Islands, arriving in Constanța. It had departed Novorossiysk on November 14 and reached the Romanian port within a few days.

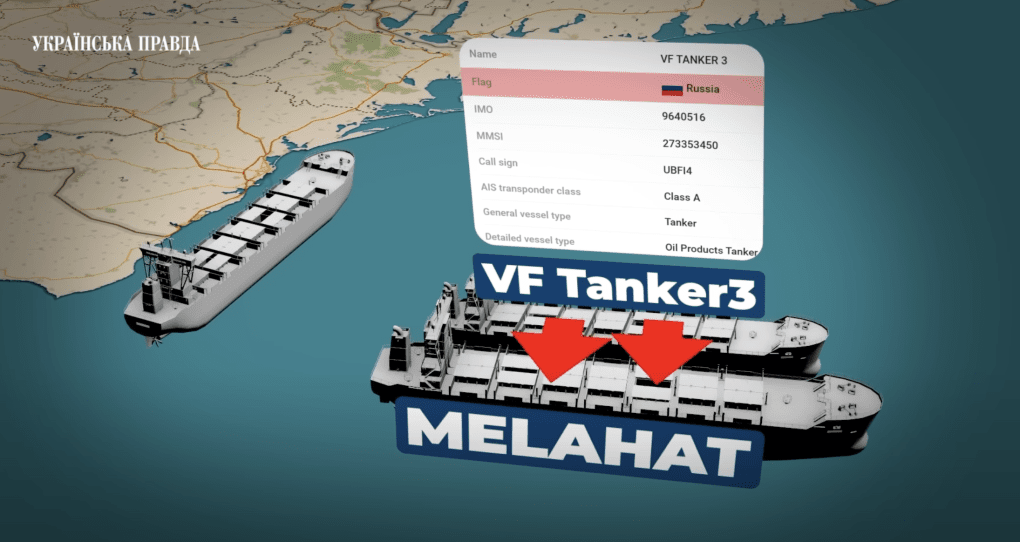

On November 26, 2024, another case was recorded. The VF Tanker 3, with direct Russian registration, docked alongside the Melahat for another transfer of Russian oil at sea.

Turkey

Journalists also highlighted cases involving tankers stopping in Turkey en route to European ports. For instance, the Seajewel and Minerva Pacific tankers, which repeatedly visited Novorossiysk in 2023 and 2024, were noted in a POLITICO investigation. Over a year, EU countries imported €3 billion worth of oil from three Turkish ports—none of which have refining capabilities.

Why it matters

In just one week, at least four tankers carrying Russian oil departed Novorossiysk for European ports, the investigation reveals. The use of ship-to-ship oil transfers at sea highlights deliberate efforts to conceal the oil’s origin—an otherwise unnecessary maneuver.

Oil and gas are the financial backbone of Russia’s war machine, projected to account for one-third of the national budget and nearly 6% of GDP in 2024, equating to $140–$170 billion. Strengthening sanctions to curtail Russian oil and gas revenues is a critical strategy for weakening Russia’s ability to continue its war in Ukraine—an effort with global repercussions, especially for Europe and its energy independence.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)