- Category

- War in Ukraine

In Russia’s “Bermuda Triangle” Brigade, Most Mobilized Soldiers Are Killed or Go Missing

The 1st Slavyansk Motorized Rifle Brigade, often called the “Bermuda Triangle,” is known for its high rates of casualties and disappearances within Russian military circles. In much of the Russian Army, conscripts are treated as cannon fodder.

UNITED24 Media has translated a recent report from “Bereg”, a cooperative of independent journalists covering Russia. The text exposes the conditions and high casualty rates of the 1st Slavyansk Motorized Rifle Brigade, dubbed the “Bermuda Triangle” for its high death and disappearance rates. It details the brutal systemic treatment of Russian conscripts, who are sent into suicide assault missions with inadequate support. Issues, including extortion and severe neglect of the wounded, underscore the exploitative and grim nature of Russia’s military operations in Ukraine.

The text has been translated by UNITED24 Media under Bereg’s Creative Commons License but otherwise left unedited.

---

In one of the Russian army brigades, most of the mobilized soldiers are either killed or go missing. This is how things work in “Military Unit 41680,” which is known as the “Bermuda Triangle.”

21:39, July 21, 2024

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Armed Forces in February 2022, about 120,000 Russians have died in the war. The Russian army loses around 200-250 soldiers each day, and these losses have been rising steadily over the past few months due to a large-scale offensive by the Russian forces. Russian troops are attacking the Ukrainian army across the entire front, opening new fronts and engaging in direct combat. Journalist Lilia Yapparova, at the request of “Bereg,” investigated the cost of this war strategy by focusing on one brigade known for its exceptionally high casualty rates. Read on to learn about the brutal treatment of Russian soldiers by their commanders, who are citizens of the self-proclaimed DPR.

This text contains strong language. If this is unacceptable to you, please do not read further.

In the winter of 2023, a group of mobilized soldiers from the Irkutsk region recorded a series of video messages, revealing how they were being sent “to the slaughter” — that is, thrown into frontal assaults without preparation or artillery support. Later, almost all of them were killed.

The soldiers were part of the 1st Slavyansk Motorized Rifle Brigade — a unit that gained a reputation for exceptionally high mortality rates because of this story. Relatives of the soldiers describe how difficult it is to obtain accurate information from the command about the deceased, many of whom are listed as missing or as having deserted for years.

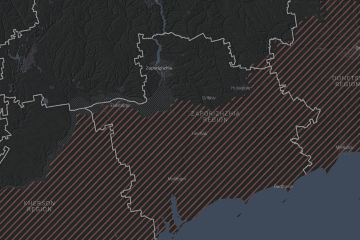

Formed in 2014 by Donetsk separatists, the motorized rifle brigade fought in Donbas as part of the DPR for eight years. In February 2022, the brigade was reinforced with mobilized personnel from the self-proclaimed republic. It suffered heavy losses during the encirclement of Mariupol and later in attempts to storm Avdiivka and the positions of the Ukrainian Armed Forces around Donetsk airport (the villages of Vodiane and Opytne). By the end of that year, the brigade joined the Russian Armed Forces. After that, the depleted brigade (referred to as “Military Unit 41680” in the Russian army) began receiving mobilized personnel and “volunteers” from Russia — the first batch came from Irkutsk. The brigade’s command staff remained largely unchanged, mainly consisting of Donbas separatist “officers.”

In 2023 and 2024, the brigade continued operations around Avdiivka. Over two and a half years of war, the brigade managed to advance about 20 kilometers into Ukrainian defenses.

“Nothing kept him here—except for life”

The body of 30-year-old Igor Anistratenko, who worked as a salesman before the war, lay under the Ukrainian village of Vodiane for just over a year. Throughout this time, his family continued searching for him among the wounded and prisoners, Svetlana, Igor’s stepmother, tells “Bereg.” When she sent search requests to Ukrainian bots, she imagined her stepson “wandering the front, forlorn,” because “nothing was known about his fate at all.”

From Igor’s comrades, she learned that on March 11 or 12, 2023, he was reportedly hit by shelling and “lay on the ground with his eyes open.” Besides this, she only heard the name “Vodiane,” which Igor mentioned in his last phone call. It was from this village that the Russian Armed Forces were then attempting to advance on Avdiivka, repeatedly sending troops to storm positions and suffering enormous losses.

Before mobilization, Anistratenko worked at the “Krasnoe & Beloe” liquor store in Valuyki, Belgorod (a border town that has been under Ukrainian shelling for a year). “He really wanted to go to the front. To see the colors of life,” Svetlana recalls. “We tried to dissuade him, but he wouldn’t listen. Nothing kept him here—except for life. He had no family—no wife, no girlfriend.”

The rookie was killed on his first combat mission—on the third day of service with the 1st Slavyansk Motorized Rifle Brigade. His body was found only in the spring of 2024: on April 22, the Anistratenko family received a call from an investigator, who reported that a “skeleton in glasses” had been found (the identification was made through an army tag; final confirmation awaited a DNA test). “He couldn’t be at that offensive due to his vision: when shooting, the targets split in front of his eyes,” says Svetlana. “But the brigade was short on people—and they just pushed everyone where they needed to.”

The unit continued to fight around Avdiivka for another year after Igor’s death, and on March 10, 2024, a contractor from Bashkortostan, Marsel Kashapov, went missing at the same front. Like Igor, he was killed during his first assault mission.

“Marsel was supposedly killed by a drone near Avdiivka—and he was left in a dugout, buried under the earth,” Kashapov’s sister Venera told “Bereg.” “Another guy from our village, Semeno-Makarovo, was already brought back and buried—but they can’t retrieve my brother. They just said: ‘We’re sorry, he’s dead.’ But where’s the body? Maybe my brother is still alive and somewhere in a basement [as a prisoner]? Maybe he’s unconscious? Maybe he’s in a hospital? Maybe he needs help?”

To prepare for such situations, Venera had asked Marsel to “tattoo her phone number on his arm”—so they could always stay in touch. He didn’t get a chance to do this: from signing the contract to his first battle, only two weeks passed. Before going to war, Kashapov admitted he was “very scared.”

Venera believes Marsel was coerced into signing the contract: “Marsel’s father (from whom I am different) had been a thief all his life. And when he went to steal pipes to [scrap them for money to pay for electricity], he took Marsel with him.”

According to her, her brother was threatened—either he goes to the special military operation or to prison—and he would still be taken to the front from there: “All the guys end up this way: those whose houses burned down, those who have no food, those with no means of existence—all are sent to the special military operation.” Venera claims that the councils of Bashkortostan receive directives from above to send one person to the front each week.

Avdiivka was occupied on February 17, 2024, but soldiers from the 1st Slavyansk Brigade continued to go missing at the front. The unit moved further—to cut off the Ukrainian Armed Forces' supply routes outside the city. On April 27, 2024, the husband of Kemerovo resident Evgenia called her from the combat area to say goodbye: “He said they were being shelled—and couldn’t advance any further.”

Another soldier with the callsign “Next” called his younger sister, Natalia from Yugra, on May 19, 2024—the day before another assault. “Natasha, light a candle for me. I’m starting to understand that this is a one-way ticket,” she recounts the last conversation with her brother. The 51-year-old veteran of the peacekeeping operation in Abkhazia did not disclose any details about the mission—and did not contact her again.

“If they said ‘captured’—fine, there’s something to hope for. ‘Killed’—it’s hard but survivable. But when you don’t know what, where, and how…” Natalia reflects in her conversation with ‘Bereg.’ “I go to bed thinking: my poor bunny, where are you? Did you eat? Can you walk? What do you feel? Just let me feel your pain, if you have any! Dream! Explain!”

The summons to “Next” arrived when he was working a shift in KhMAO. Within three days, he was already near Donetsk. His sister claims she found out about it only when he was already at the assembly point and didn’t have time to dissuade him. He didn’t share details of his decision with his family. Only after his disappearance did Natalia find out that he had been wounded, lying in a hospital but didn’t receive adequate treatment. Later, with a knee injury, a hand wound, and shrapnel wounds, he was sent back to storm—“under-treated, limping, with a bandaged leg.”

“Only now, after he went missing, did I gather information from his friends,” says Natalia. “I didn’t even know he was wounded! That he was in the hospital. It turned out he had a knee injury and a hand wound. Nothing was treated, and the shrapnel wasn’t removed. And that’s how it stretched out—he went into that assault limping, with a bandaged leg.”

When she inquired about her brother, the brigade responded with two short phrases: “We are doing everything possible” and “Sometimes, the guys come back.” “At such moments, I want to ask them if they’ve ever seen videos from drones, when the abandoned [left without support] are finished off,” Natalia says. “God, it’s so terrifying to watch, but I look at that channel to see where my brother is, where he could be.”

In the same assault as “Next”—on May 19, 2024—Omiich

Igor went missing, whose wife, Tatiana, is searching for him. In their last conversation, he mentioned going for a nighttime assault on the village of Netailovo near Avdiivka. “They were given a target that no one could take,” Tatiana recalls. “But it was taken since then! Just not by my husband, but by others. And he went missing.”

Igor signed his contract on April 10, 2024. “We used to argue a lot because instead of earning money—since we have four children—he had been drinking lately,” Tatiana says. “Then people from the enlistment office came to recruit him—cleverly, while I was not home. And under their influence, he went and signed everything—and we couldn’t do anything.”

The Russian troops occupied the entire Netailovo a week after Igor went missing. “The brigade commander said my husband was not listed as ‘killed’ or ‘wounded,’” Tatiana says. “I visit elderly women every day to ask if they know anything about him. I contact Ukrainian chatbots. I’m very worried about a photo of prisoners because there’s a person who looks like Igor. Just the uniform is a bit different—and the boots are a different color. But I still haven’t deleted it.”

Relatives of the soldiers have organized their own search and exchange contact details of the command, photos, and call signs on social networks. Sometimes, people searching for individuals from other units (or even those who don’t know exactly where their relatives served) accidentally join these growing “search” threads and chats.

“Bereg” has contacted several dozen such families. They refer to the 1st Slavyansk Brigade as the “Bermuda Triangle”—partly because little is known about the unit itself: soldiers who end up there disappear or die too quickly.

“You bastards, what the hell were you waiting for, mobilization?”

Maxim Bykov from the village of Semenovka in Saratov is one of the few who managed to describe in detail to his relatives how the service in the 1st Slavyansk Brigade is organized. He signed his contract on May 13, 2023 (he needed to pay alimony), and stopped contacting on June 6, 2024.

Bykov and other recruits were assigned to “officers” from the DPR. At the first formation, the commander greeted the mobilized Russians with the words “Russian meat has arrived.” “He ordered them half in Ukrainian, half in Russian: ‘Russian meat, tally up as 200 or 300! ’—meaning those he would kill and those he would wound,” recalls the contractor’s sister, Tatyana Anufrieva.

The DPR’s “militia” brigades suffered significant losses at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. They are now being replenished with Russian mobilized soldiers. “Commanders live in Donetsk with their families and hate us because they have been fighting there for 10 years or however long—and we were just sitting and waiting—and only now are helping them,” says Tatyana. “‘You bastards, what the hell were you waiting for, mobilization? Why didn’t you come earlier? We’ve been fighting here for so long! ’”

Donetsk “officers” called the Russian mobilized soldiers “moskals,” and, according to military relatives, “yelled at the recruits”: “You came here to earn money? So, go to work—your families will be happy with the compensation [for death].”

New recruits were sent on assaults every two to four days, “without a break,” adds Anufrieva. “My brother would return from a mission, and that same night they’d send him out again—wounded or not—to evacuate: to get their own out.”

The Donetsk command did not account for the losses among mobilized Russians, using them in assaults without artillery support. According to Anufrieva, those who refused to go were beaten and threatened with “zeroing”: “They didn’t kill them right away but took them out to the field in their underwear and a T-shirt. They were given a knife or a shovel—and that was it, goodbye. They didn’t come back to the unit.”

Her brother told her that those who were afraid during an assault and tried to retreat were shot by their own from mortars. “We’re not needed here,” he summarized.

Before each assault, Bykov would call his older sister, whom he called “nanny,” and warn her: “Nanny, we’re going on an assault!” During his months of service around Avdiivka, Maxim had his foot broken, his right hand shattered (he continued to fight in a cast), and received shrapnel wounds to his chest, thigh, elbow, and calf. “His legs were like a sieve from shrapnel,” says Tatyana.

She learned about some injuries by accident. Once, Bykov sent her a photo of his tattoo: he had a short prayer tattooed just above his solar plexus. Anufrieva looked closely at the picture—and saw a fresh scar under the lines. It turned out that during the last assault, a shrapnel piece had pierced his chest, almost hitting his heart—and he had his first tattoo done so that he could “always be recognized.”

In January and February 2023, the skies over Avdiivka were completely controlled by Ukrainian drones, Tatyana recalls. Her brother was pleased that he could run fast, like he used to in school, and thought he might be able to “hide from them.” To protect themselves, the soldiers were ordered to move underground through a pipeline discovered by reconnaissance. So, Maxim “took off his greatcoat because the pipe was too narrow and crawled through what was either a sewer or a heating main, while the Ukrainian forces were driving them out with some kind of gas,” Anufrieva recounts.

The only warmth during the assaults was in that pipe. When Bykov returned from a February mission to Avdiivka, his toes were frozen black. He wasn’t sent to the hospital, and in the unit, his sister says, “there was no proper treatment—just smeared with ointment and bandaged.” To walk, the soldier had to find shoes one size larger.

Despite the frostbite and the cast, Bykov continued to be sent on evacuations. “One of his comrades had a drone hit him in the stomach so hard that his intestines came out,” Anufrieva says. “As soon as Maxim evacuated him, he got beaten and was sent back [to the front].” Bykov was only sent to the hospital in March when he lost consciousness right at the brigade’s location.

Comrades described the aftermath of his fainting, Anufrieva recalls: “Tanyukh, his whole body was swollen! His head was even swollen. He was all puffed up and burning.” Soon, her brother called her himself: “Nanny, send [the commanders] 50,000 rubles so they’ll put me in the hospital. Otherwise, they won’t.”

“Soldiers were afraid to even open their mouths”

The brigade commanders extorted money for everything, Anufrieva recalls (her account is confirmed by five other relatives interviewed by “Bereg”). According to her, commanders demanded “tens of thousands” for “concessions,” 200,000 rubles for failing to show up for a mission, and 500,000 rubles to avoid combat missions for a couple of months.

Commanders also kept a significant portion of the compensation for combat injuries, only officially registering injuries if the soldiers paid them one million rubles after receiving the money. Extortion didn’t stop there. “Every month they took 50,000 rubles supposedly for construction and repairs. Even to go on an assault, we had to chip in for gasoline, water, and cigarettes,” Anufrieva lists.

In a hospital in Donetsk, it was discovered that Bykov had developed bilateral pneumonia and blood poisoning. Additionally, he was diagnosed with kidney inflammation and heart issues. Doctors suggested amputating his blackened toes to prevent gangrene. They also found a misaligned hand under the old cast. “His pinkie was embedded into his palm,” Anufrieva says. “And the other fingers were sticking out in different directions.” Without serious treatment in a well-equipped hospital, “your brother won’t survive more than a year,” Tatyana quotes the doctors' prognosis.

She regrets not pushing for his hospitalization earlier. But Maxim begged her not to interfere. “Nanny, don’t complain anywhere! Please! Don’t complain anywhere—it will only get worse!” Anufrieva recounts her brother’s pleas.

“Soldiers were all afraid to even open their mouths,” explains the soldier’s sister. “For example, when we, the wives [of the new recruits], wrote letters to the prosecutor’s office and the Investigative Committee (in Rostov, Saratov, Moscow, Donetsk) and even made a complaint to the president, he called me in a panic: ‘Nanny, where did you complain? The commander gave me a beating: hit me in the ear with a rifle so hard that it turned blue. Don’t write anything else! Don’t complain about anything—otherwise, they’ll zero me out! ’”

This is how the brigade’s command ensured that information about the state of affairs in the unit did not leak out. For complaints about local conditions or refusal to go on an assault, soldiers were locked in basements, handcuffed to stair railings, or taped to bunk beds. Bykov spent one night in such a condition—without food or water.

“To keep them from complaining and getting upset, they also put them in pits without food, holding them there for up to a week,” Tatyana recounts. “They survived only because their comrades secretly fed them: throwing in rolls, sandwiches, and water.”

What the commanders’ cruelty meant for her brother, Tatyana doesn’t know—she only remembers how one of the senior officers threatened Bykov before a mission: “If you survive on the front line, I’ll zero you out.” Maxim survived and ended up in the hospital, from which he was taken away on June 6, 2024, by two unknown men in a civilian car.

At that moment, Bykov managed to call his mother: “They’ve come for me—they’re taking me back to the unit.” By the evening of June 7, Maxim’s acquaintances started receiving similar messages. Someone, pretending to be her brother, asked for money, Anufrieva recalls. He wrote to her: “Sister, send 15,000 urgently! I’ll send you the card number.”

Tatyana immediately realized it wasn’t Maxim: “He never called me ‘sister’—only ‘nanny.’ Even when the guys asked, ‘What’s your sister’s name? ’ he would say: ‘Nanny! ’ I’m five years older than him—I raised him.”

Since then, Maxim has not been in touch. His number is disconnected; the brigade told Tatyana that he had “left the unit without permission.” Anufrieva doesn’t believe it.

“Mommy, did Dad call?”

Out of 252 of Bykov’s comrades, only four remain in touch, says Anufrieva—the rest of the mobilized soldiers he served with are listed as missing or dead. About 500 relatives of such soldiers are now corresponding in a general WhatsApp chat (one of many similar chats existing in different messengers and social networks). “Otherwise, one could go crazy. Because the commanders don’t answer the phone, don’t respond to messages, change numbers. We get only official replies everywhere,” Tatyana says.

“I scroll through the feed: a sixth batch has already gone on combat missions since my brother went missing. And no one returns! No one comes back!” complains Natalia, who is searching for her relative. “All I hear is: ‘Poor guy, ended up in the most dangerous unit.’” Svetlana, Igor Anistratenko’s stepmother, agrees: “It seems to me that practically all of our rotation has died.”

Larisa Mamaeva, who is searching for her missing brother from two months ago, says that soldiers refer to such mortality as the “algorithm”: “No one serves there for more than six months: if they get out of one assignment, they won’t make it out of the next. My brother was incredibly lucky in the first week [in the brigade]: he got through one assault, then another. He said: ‘I can’t believe how lucky I’ve been! Out of the crowd we went with, only I and one other boy are still intact.’ And then they sent him and the other boy back again in a couple of days. And now, he hasn’t called or written for two months.”

Two of “Bereg’s” interlocutors even tried to go to the front themselves to find their brothers but realized it was impossible. Natalia, who is searching for her brother “Next,” recounts her attempts:

I asked humanitarian workers to take me with them. Just to leave me there to search every inch. Of course, I was quickly told that I was “insane” and simply wouldn’t be allowed in. Living with this uncertainty is very hard. “Wait, wait, wait.” It’s impossible to wait. Uncertainty kills. His son cries every morning: “Mommy, has Daddy called? Mommy, has Daddy shown up?”

Venera, who lost her brother Marsel at the front, also plans to contact search teams—and is ready to go to the front herself: “I want to bring at least his bones home. So that Mom can go to the cemetery and clean the grave. My mother is now bald. I see how her hair stays on the comb—right with the roots. We’re searching for him—and we can’t find him. Either alive or dead—we can’t find him.”

Alexey Pavlov from Perm region spent only two days in the unit—and was killed in February 2023 in his first battle near Avdiivka. He returned home in a closed coffin. For his service, he was awarded an order, his sister Tatyana Kargasina says. She reads the award documents for “Bereg” in full.

They state that 49-year-old Pavlov “liberated” Donbas “from the criminal Kyiv regime,” “inspiring the personnel to heroism and bravery”—and despite a shrapnel wound, “continued to carry out… combat tasks,” allowing “the infantry… to secure an enemy firing position.”

Kargasina, however, sees her brother’s death quite differently: “He was killed in the first battle and didn’t understand anything about the war! And we still can’t believe he’s gone. Maybe if we decided to open the coffin… But as it is, we can’t believe it. He was earning well as a tractor driver in the collective farm. I now think we did a bad job dissuading him.”

Kargasina wishes for the war to end—but she has no hope for that. “

Given what is reported on TV about the trillions and billions of thefts in the Ministry of Defense, it’s hard to believe it will end soon,” she reflects. “War is money. I was just reading about General [Yevgenia] Vasilieva, who was before the current [corrupt officials]—she was one! And here it’s just pure horror. People collect money for the army, clothe it, feed it—and they steal it by the billions and trillions.”

She explains the start of Russia’s war with Ukraine as follows:

“Putin believed his ministers that our army was ‘all set, let’s start, and in three months we’ll be at the border with Poland! ’ But what did we have? We had nothing to clothe the soldiers, feed them, or fight with. My nephew’s money was collected for a drone. Is it really our job to buy drones? They are bought just like that in the store! Can’t the Ministry of Defense manage?”

The [Russian] Ministry of Defense did not respond to Bereg’s inquiries about the 1st Slavyansk Brigade.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)