From trench warfare to the use of modern technology, the war in Ukraine is one of contrasts. We look at the world's most mine-contaminated landscape and how robots and AI are being introduced to combat the crisis.

While the Ukrainian military sits in self-dug trenches, they’re also revolutionizing modern warfare by using AI software and drone technology in their fight against Russia. That is why many say that this is the most technological war the world has ever seen—and it’s no different when it comes to land mine clearance.

Ukraine has traditionally been called “the breadbasket of the world”, but today its prime agricultural lands have been decimated by mines and explosive ordinance devices (EODs).

According to Ukraine’s Minister of Economy, Yulia Svyrydenko, it could take over 700 years to clear Ukraine’s lands. An estimated 29% of the country is contaminated with landmines—making it one of the most mined countries in the world.

Mines and EODs present a real threat to military personnel and civilians. They cause injuries and deaths as well as affect farming and agriculture, preventing access to infrastructure, homes, land, and roads.

Ukrainian authorities, NGOs, and volunteers work tirelessly to free the country from landmines—but it isn’t an easy job. Now, robotics and AI technologies are being introduced to mine clearance efforts in the hopes of freeing Ukraine’s land faster.

We take a look at the latest technology and speak with two deminers, British and American, about whether tech, above human clearance, will free Ukraine from landmines.

Landmines, EODs, and their effects

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, mines and EODs have reportedly caused a total of 1,112 casualties, 343 of which were fatal—including 270 civilians.

Russia’s armed forces have been relying heavily on fortifications and dense minefields to create challenges for Ukraine in their counterattack operation. That is why different types of landmines now litter the landscape in Ukraine:

Anti-personnel mines (APMs)

Anti-personnel mines (APMs) are designed to target enemy soldiers but are also used against civilians. APMs are made to debilitate or amputate those who detonate them—causing long-lasting pain and trauma—but not always kill.

It has been reported that up to 50,000 Ukrainians have lost their limbs during the war, though this isn’t just because of landmines.

APMs are sometimes buried just a few inches under the ground or placed on the surface and can be activated with a pressure plate or with a booby trap. Russia is known to have used at least 13 different types of APMs since February 2022, attaching numerous victim-activated booby traps to them while retreating from positions that they had once occupied.

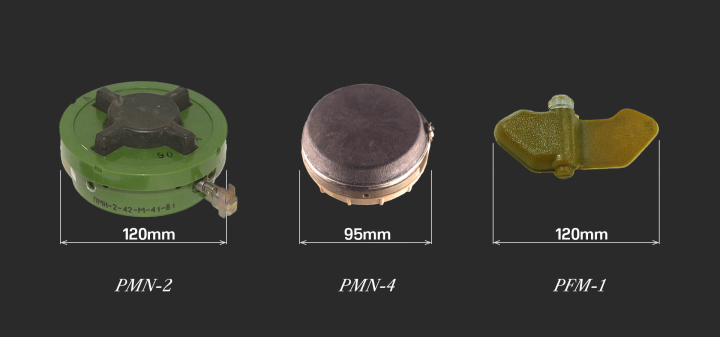

APM Ground mines: Russia most commonly uses the PMN-2 and PMN-4 mines. But the most controversial that Russia uses is the PFM-1, also known as the “butterfly mine”. It can be fired from rockets and scattered indiscriminately over a wide area, easily blowing off the foot of an adult or a child who may step on one.

![]()

“They are very dangerous, especially for civilian populations,” said Tymur Pistriuha, Head of the Ukrainian Deminers Association. “It is like a leaf. In grass, it is difficult to identify.”

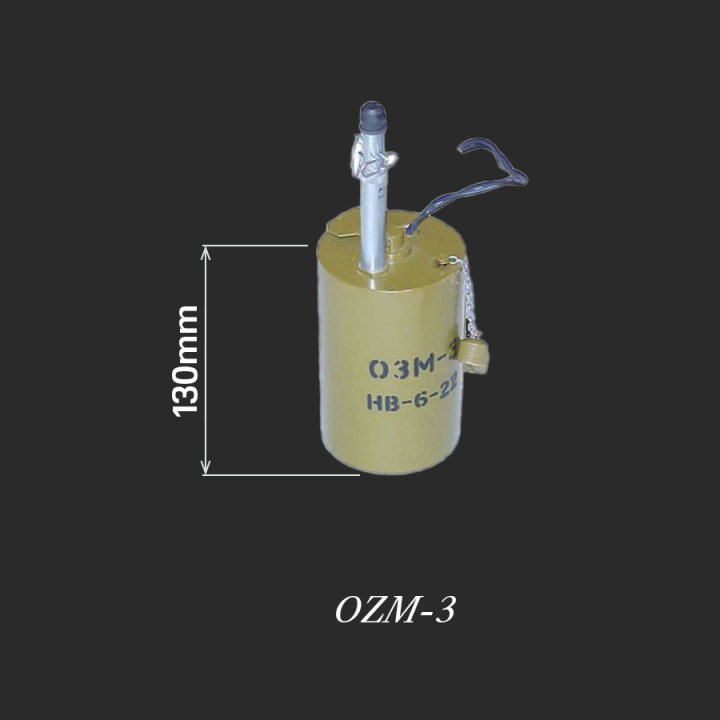

APM Bounding mines: These mines are often triggered by either tripwire or pressure. Once activated, they can go up 3 ft into the air—-then explode and cause horrific injuries. A man searching a local forest for items looted from his home during Russia’s failed Kyiv offensive, triggered an OZM bounding mine rigged to a tripwire and was killed in the blast.

![]()

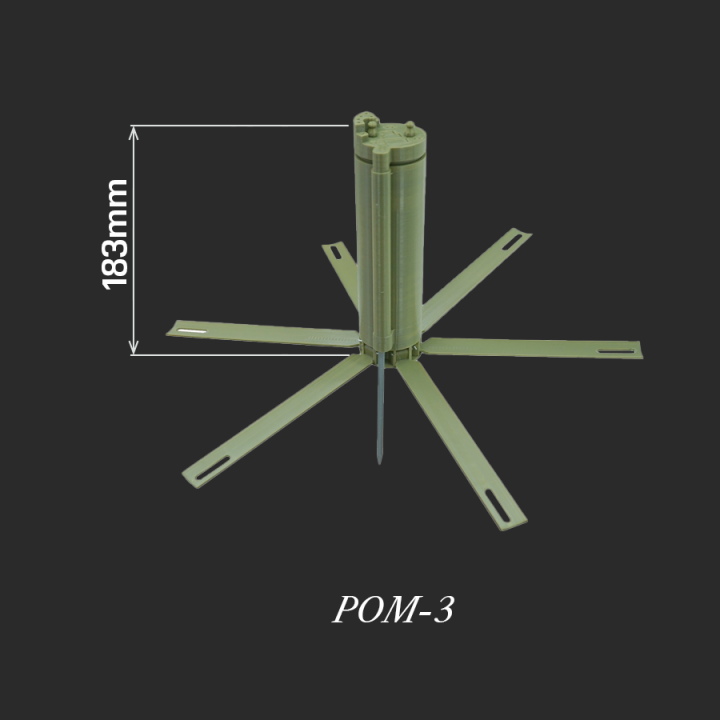

APM Fragmentation mines: These are found in bounding and ground mines. When detonated, they send metal and/or glass shrapnel in different directions—- from up to 660 feet away. One of the Russian force's newest is the POM-3, activated by its seismic sensor—detecting ground movements and vibration of the soil. Footsteps near the mine will trigger the sensor to jump 1/1.5 meters out of the ground before detonating. POM-3s were first seen being produced by Russia in 2021.

![]()

Anti-Tank / Anti-vehicle mines:

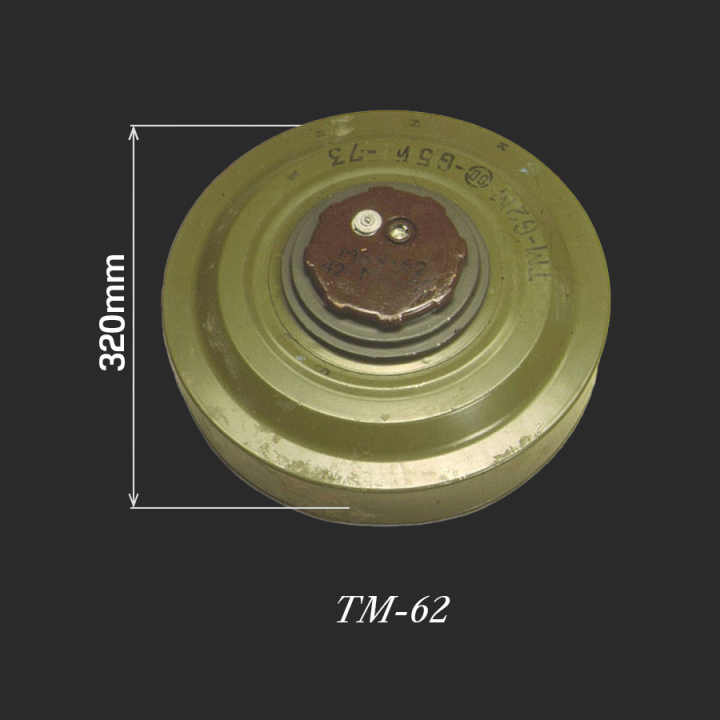

Anti-tank mines are designed to cause heavy damage to vehicles, tanks, and their crew with explosive charges of approximately 2kg to 10kg.

The most common type of anti-tank, anti-vehicle mine—used by both Ukraine and Russia since Russia’s full-scale invasion—is the TM-62, highly explosive and equipped with an MVCh-62 pressure-activated fuse.

![]()

A story from a British deminer

“I wanted to tackle the landmine crisis in the poorest regions, helping the people that are affected the most,” Harley Whitehead—a UK deminer (sapper) in the Ukrainian Volunteer Army (UDA)—told us earlier this month.

He has had a passion for supporting Ukraine since 2019 through various humanitarian efforts and fundraising but officially started his demining work in 2023—after training in Kosovo. “Ukraine is my future home where I want to see out my days, until the end.”

Harley is currently working across the Kherson region, clearing the frontline to make way for military forces and local farmers—working under extremely tough conditions.

“There's a lot of booby-trapped landmines rigged with ALDs, as soon as you lift the mine, it'll blow the whole thing-killing everybody,” he explained. “A common booby-trap is in the Cheburashka toy, I guess because the bear is an icon from the Soviet times, moving it detonates whatever is inside it.”

Since June 2023, Harley’s small team has removed 9,700 munitions, and as of March—1,700 in 2024 alone.

Robotic and AI demining systems

Demining is a dangerous job so Ukraine and its Western partners are working on supplying the country with a variety of robotic and AI demining systems to keep their sappers safer.

Palantir and the Government of Ukraine have created a partnership to develop AI software aiming to demine 80% of potentially contaminated land within 10 years. The platform—which was piloted in 2023—makes a data map between key infrastructure and hazards, showing how EODs impact certain areas like roads, hospitals, and farmlands—to ensure that the most hazardous and important areas are safely cleared first.

UGVs are becoming increasingly popular too. In February 2024, the European Union provided Ukraine with the DOK-ING MV-10 remote-operated mine clearing system, which is currently being used in both Kherson and Mykolaiv, demining up to 4000 sqm per hour. South Korea delivered 10 other variants of the DOK-ING robotics to Ukraine in December of 2023.

Germany has also given Ukraine the Swiss-German robotic GCS-200—a heavy-duty mine clearance system performing at a speed of 12,000 sqm. It first arrived in Ukraine during the winter of 2023 and more will be delivered in the spring and summer of 2024.

Ukraine is also making its own UGVs to help with the demining efforts. The latest is the Ratel Deminer, a system that can be operated remotely and has already been tested in the Donbas region. It has a daytime vision camera and destroys mines such as PFM-1, PMN-4, PMN-3 and PMN-2.

Will UGVs keep sappers safe from demining?

Harley supports new UGV and AI demining equipment working in certain areas, but has several concerns about the frontline: “Demining under shelling is hard, but our biggest threat is Russian FPV drones.”

“I always say that these new machines on the frontline won't last two minutes. All it takes is a $500 FPV drone to destroy a multi-million-dollar machine. Human, manual clearance is vital and the only kind of clearance that would work directly on the frontline. An element of both is needed, investing in these machines to tackle the problem quickly in areas of the front is a good idea, but here, where we work, they would be targeted and blown up.”

He says that more competent sappers with better equipment are needed to support any counter-offensive. Sometimes, untrained, and uneducated sappers can leave areas incomplete and in dangerous conditions.

Stu Miller, an American sapper with his own non-profit organization Invictus Global Response agreed with Harley: “Training and certifications are paramount. Unfortunately, there are instances where people have little to no experience and try to jump right in supporting demining efforts.”

Stu has been demining for over 10 years, mainly in the Middle East and Africa. While in Afghanistan in 2006, he was injured by running over two anti-tank mines. Luckily he evaded amputation and life-changing injuries and was then inspired to form his own non-profit.

Stu has worked with a variety of robotic demining systems but says that they’re “quite expensive and labor intensive to keep running. In the right circumstances, they can be a real advantage for deminers.” Though, he notes, they’re not the “silver bullet” to the mine clearance problem. “Even after a machine runs through an area, the ground has to be checked.”

What’s next?

Last year, the concept of a British Centipede dragon was discussed at a conference in London. It is thought to be more resistant to detonation, anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) and artillery than other "traditional" demining systems. There is, however, very little information on the Centipede and it remains to be seen whether it is still in its development stage or currently being tested.

Monty, a friend of both Harley and Stu, lost his foot in an APM incident last June, while the danger is present in the minds of sappers, they continue to do vital work for Ukraine.

A few hundred demining robots will not change the status of this war, but they will certainly help build communities and bring farmland back to a safe state. Since drone warfare has grown from a small fleet to a million-strong force, there are hopes that the use of UGVs will too. Yet, Harley's team hopes to train more volunteers this year to competently clear the path for a safer Ukraine.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)