- Category

- War in Ukraine

Russia’s Economy Doesn’t Match Its Ambitions, with NATO Countries Still Having a Significant Advantage

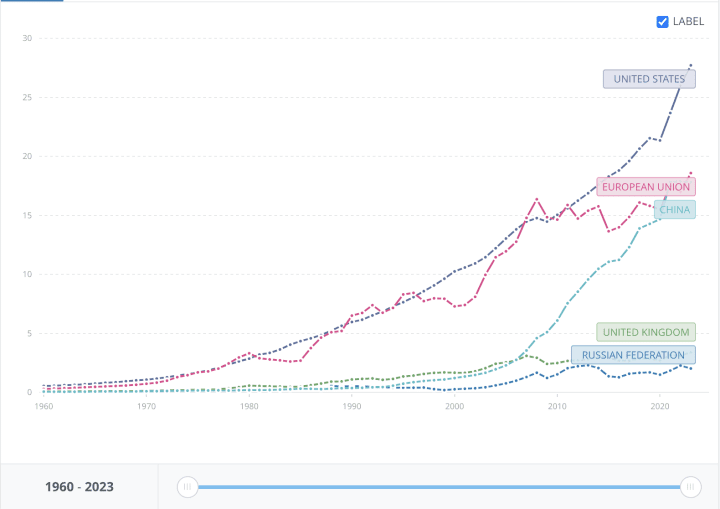

Behind these loud ambitions and attempts to renegotiate global influence lies a conventional resource-based economy. Although the territory of the Russian Federation covers 1/6 of the Earth’s landmass, its economy is by no means comparable to the world’s largest economies like China or the United States, despite the Russian leadership’s efforts to present it as such.

While in the past, Russia's desire to influence the politics of third countries was largely limited to the post-Soviet space, today, Russia openly declares its intention to influence the American-centric world that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Russia no longer hides its verbal aggression toward several European Union countries, its military presence in several African states is growing, and plans for the militarization of the Arctic are underway.

When we look at the U.S. economy—the country with which Russia is primarily trying to engage in dialogue—Russia's economy is dozens of times smaller. The U.S. remains the world’s largest economy, with a GDP approaching $30 trillion in recent years. Meanwhile, despite high prices for its main raw materials, Russia's economy hovers around $2 trillion.

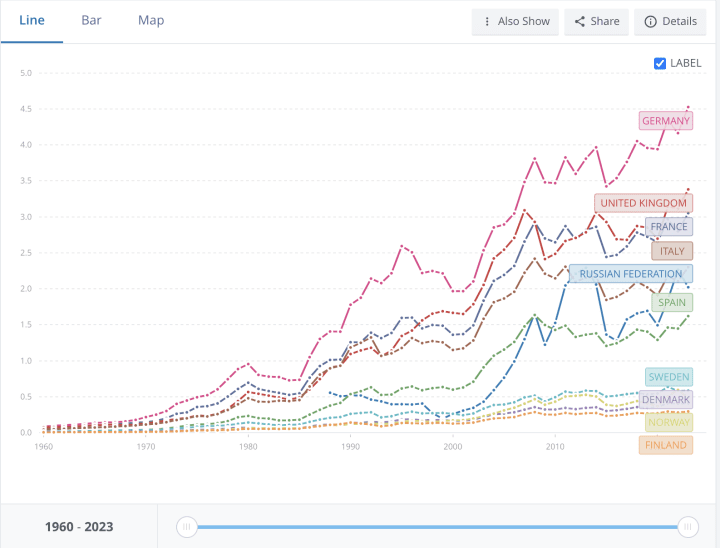

Russia's economy is ten times smaller than that of the entire European Union or China. In fact, it is even smaller than that of the United Kingdom—a much smaller country both in terms of land and natural resources.

Russia also lags behind several major European economies, including Germany, Italy, and France. Its GDP is roughly equal to the combined GDPs of four Nordic countries, which have significantly smaller territories and populations.

At the same time, Russia cannot compete with leading countries in terms of regular defense spending. In 2024, the U.S. defense budget exceeded $800 billion, while Russia spent about $110 billion that same year—in the midst of a war.

Vladimir Putin proposed a 50% reduction in the military budgets of both the U.S. and Russia. However, given the absolute values, this offer seems more like a bluff: U.S. defense spending is eight times greater than Russia’s.

For Russia, such a cut would essentially mean a return to the pre-war period, when it typically spent no more than $70–80 billion on defense annually.

Russia plans to increase its defense spending to $141 billion in 2025, but despite Putin’s confident rhetoric, the economic statistics speak for themselves. Russia faces a record budget deficit, and its reserves—built up over the past 15 years—could be depleted as early as this year at the current rate.

The liquid portion of the National Wealth Fund fell to $30 billion in March 2025, down from over $110 billion in 2021, before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s Ministry of Finance had planned to replenish this fund using additional oil and gas revenues. However, with the price of Urals crude dropping to $50 per barrel, that promise may remain unfulfilled unless Russia implements a budget sequestration.

What are Russia’s economic strengths, and can they be weakened?

A defining trait of Russia’s economy is its reliance on certain technological legacies of the Soviet Union. However, today Russia is incapable of developing or reproducing most technological systems without foreign technologies. Nearly every weapon system it produces now relies on Western equipment.

Despite repeated attempts to diversify the economy, Russia still largely depends on energy prices, which have remained high in recent years. Energy resources remain the key source of budget revenue.

Formally, oil and gas account for about 30% of the federal budget, but they also indirectly fuel a significant portion of tax revenues from adjacent industries and consumption.

Despite the sanctions, Russia has managed in recent years to bypass restrictions and continue earning hundreds of billions of dollars—funding its military and other expenditures. Stable foreign currency income from energy exports is Russia’s primary economic strength—but it is also Putin’s Achilles’ heel.

Another strength typical of autocratic regimes is that these revenues do not have to be spent on improving public welfare. Instead, they can serve the ambitions of the ruling elite, the security apparatus, and militarization. After all, North Korea developed nuclear weapons despite having an underdeveloped economy—but not without technical support from the Soviet Union.

In Russia’s case today, this means two things:

The world must consolidate efforts to strengthen control over the export of dual-use technologies to Russia—those that could reinforce the Russian military-industrial complex.

The international community should work together to ensure that the Russian population understands that supporting the aggressive militarist policies of their current leadership has consequences—not only for the elites but also for those who support them.

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)