- Category

- War in Ukraine

The Daily Lives of Russian Prisoners of War in Ukrainian Camps and Their Conditions

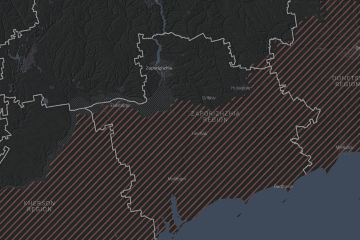

The Zahid-1 camp for Prisoners of War (POWs) is located in the west of Ukraine, about a thousand kilometers from the frontline. For many Russian POWs, it is the farthest they have been from home. For most of them, Ukraine is the first foreign country that they have visited, in this case, without an invitation.

The majority of these POWs come from remote regions of the Russian Federation, areas with depressed economies and low living standards. The main motivation for many of them to join the military is the salary.

They primarily learn about the war in Ukraine that Russia has started from TV, where they are told that NATO troops are already in Ukraine, near the Russian border. However, for some, the conditions here are even better than those in Russia.

We visited the Zahid-1 camp, where we saw firsthand how POWs live and also had the opportunity to talk with some of them.

First steps through the camp

All newly arrived Russian POWs go through a standard procedure: they hand over their personal belongings, shower, and get haircuts. They are given identical sets of uniforms and personal hygiene items.

After that, they are quarantined in a separate building where doctors conduct full examinations and provide medical assistance if necessary. In addition, psychologists also communicate with them.

After two weeks of quarantine, the new arrivals are transferred to the “general zone.” They are introduced to their new daily routine, rules, and responsibilities. The camp staff have the rules for the treatment of POWs, as defined by the Geneva Conventions, printed.

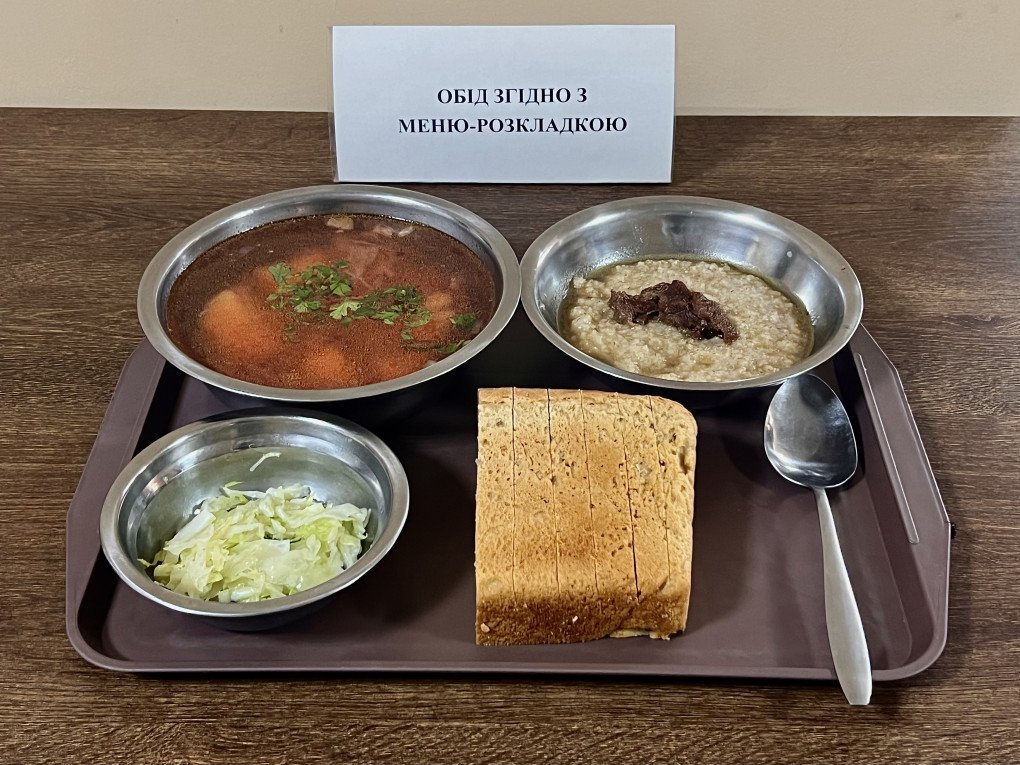

All other work, such as cleaning and cooking, is done by the prisoners themselves. They even bake their own bread, which is prepared according to recipes that meet daily nutritional standards.

“When I was in prison [in Russia], my food there was several times worse. The conditions in general were several times worse. I could not imagine that there could be such good conditions here,” says Alexey, a mobilized citizen of the Russian Federation.

After morning hygiene procedures and making their beds, POWs have an hour for breakfast from 6:50 to 7:50. Then they go to formation, where the guards check the number of people present. From 8:30 to 16:30, with an hour break for lunch at 12:30, the Russian prisoners work in workshops making chairs or assembling artificial Christmas trees.

Once every few months, one person is elected for the librarian position. Their duties include issuing and re-registering books and cleaning.

For their work—six days a week—the prisoners get paid. The amount they are paid is determined by the provisions of the Geneva Conventions. They can send this money to their relatives or spend it at a local store, for example, to buy cigarettes or sweets.

“Although officers have the right not to work according to the Geneva Conventions, everyone chooses to work because time passes faster,” says Vitaly Matviyenko, a representative of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of POWs.

After the workday, Russian POWs have two hours of free time until 19:15. They can visit a sports field, a local church, or private rooms for Muslims.

They can also communicate with their relatives by phone or receive parcels from them at a pick-up point.

If desired and under certain conditions, relatives can meet with POWs, but not on camp premises. However, the staff notes, that this is extremely rare as relatives of POWs do not often express this desire.

An admission of guilt or a desire to repeat?

While families of the Ukrainian military have not had any information about the location and health status of their relatives in Russian captivity, Russian families have the opportunity to check the status of their relatives either in the Ukrainian database “Khochu Nayti” (I want to find), or be notified by the Red Cross, which also forms lists of Russian military personnel for exchange.

The Russian POWs we spoke to in the camp unanimously recognize the satisfactory conditions of their captivity but do not comment on the conditions faced by Ukrainian POWs in Russia.

However, they express their surprise at how much their idea of being captured in Ukraine differs from reality.

“We were afraid that the Ukrainian military would torture us to death. Mostly we are advised to kill ourselves before being captured. But in reality, [he Ukrainian military] even gave me a cigarette and treated me quite normally,” recalls Alexander, a mobilized citizen of the Russian Federation.

Despite this and full access to any news outlets, the Russian POWs still repeat narratives from Russian media.

“When the mobilization was announced, it was said on television that this was due to the fact that NATO troops are on the territory of Ukraine. Although I didn’t see them during my time at the front,” says Pavel, a mobilized citizen of the Russian Federation.

However, the Coordination Headquarters notes that the words of the Russian POWs should be treated critically. Many of them have been developing their “sincere legends of the innocent” for months. Some, who had previously served time in Russian prisons, for years.

Most of them seek to justify themselves to the Ukrainian side and return home. But they still avoid discussing the responsibility of the Putin regime for the war or their own responsibility to the Ukrainian people.

But there is a percentage of those who not only do not talk about their responsibility, but also return to the front again after being exchanged.

“They don’t talk about it openly. But there are cases when, almost immediately after exchange, Russians return to service. The Ukrainian military told us about how after a battle, they recognized a deceased Russian soldier who was recently exchanged,” says the representative of the Coordination Headquarters.

Only one or two percent of the total number of POWs genuinely feel and admit their guilt.

“Those with critical thinking, who watch Ukrainian TV, read international news, and books, realize that reality is different from what is broadcast in Russia. For such thoughtful people, the project 'Khochu Zhit' (I Want to Live) was created. If a POW did not commit war crimes, they can choose to be exchanged or, after our victory, seek political asylum,” says Vitaly.

Not only Russians

The camp also holds Ukrainians forcibly mobilized into the Russian army from occupied territories. Those who correctly surrendered and supported Ukraine will be released after a certain procedure.

For example, Yevhen, originally from Novoazovsk, Donetsk region, lived with his mother in Russian occupation for more than eight years. In his city, located ten kilometers from the border with Russia, the flag of Russia was raised back in 2014.

On February 24, 2022, Yevhen woke up with a feeling of deja vu—sirens, explosions and another Russian offensive. He tried to film the movement of Russian troops and share data with the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

In November 2022, he was captured by the Russian military while filming a strategic bridge. They handed Yevhen over to FSB officers, who, as a result of lengthy “conversations”, brought the man to a military unit. From there—after quick training—Yevhen was sent to the front to fight for Russia.

“They argued that I should atone for my sins before Russia, even though I am a citizen of Ukraine. I was on the contact line for six days, where my tasks were to carry water, ammunition and the dead. Then they sent me to the assault, where, as punishment, I had to go first,” recalls Yevhen.

Yevhen always had a white T-shirt with him, which he called his “mascot.” Before the assault, he removed it to use it as a white flag to surrender.

He says that during the fighting, when a Ukrainian reconnaissance drone arrived to correct the operation of the mortar, Russian soldiers began to hide. So he took advantage of the moment and ran across the field. He ran 200-300 meters under fire, waving his T-shirt all the time.

Running to the positions of the AFU, Yevhen raised his hands with a white T-shirt and said that he was surrendering.

In the case of Yevhen, who was forcibly mobilized from the Ukrainian occupied city to join the Russian army, all relevant checks have already been carried out and legal work continues to completely remove the status of a POW from him.

His mother has already been evacuated to the territories controlled by Ukraine. Yevhen, while waiting for his release, stays in the POW camp.

How to properly surrender?

Despite the intimidation of Russian propaganda, surrender is often the only way for Russian soldiers to save their lives. For this purpose, Ukraine has developed an algorithm of actions one must take to voluntarily surrender within the framework of a Ukrainian state project called “Khochu Zhit”.

It was established by the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of POWs with the support of the Ministry of Defense and the Main Intelligence Directorate of Ukraine.

Ukraine guarantees that all those who voluntarily surrendered will be registered as “captured in battle.” This will preserve all payments and benefits from the Russian army during their stay in a Ukrainian POW camp.

The list of actions during a correct surrender also includes removing the magazine with cartridges from the machine gun and moving it to the left shoulder with the barrel down. In addition, before that, a Russian soldier can contact a 24/7 hotline of the project “Khochu Zhit” or leave a request in their chatbot.

Representatives of the project report that so far—only within the framework of this project—more than 300 Russian soldiers have voluntarily surrendered.

After that, all of them are checked, in particular by the Ukrainian special services, including through a polygraph test. If the prisoner of war really did not commit war crimes, then he is guaranteed amnesty, as well as the opportunity to apply for asylum in Ukraine or Europe.

In general, there are already three similar camps for POWs in Ukraine. Two more were opened this year alone.

“Given that Russia is disrupting the exchange of POWs, and the number of Russian military prisoners themselves is growing every day, these camps will not be the last,” says Vitaly Matvienko.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)