- Category

- World

Are Modern Autocracies Collapsing Under Their Own Weight, Like a House of Cards?

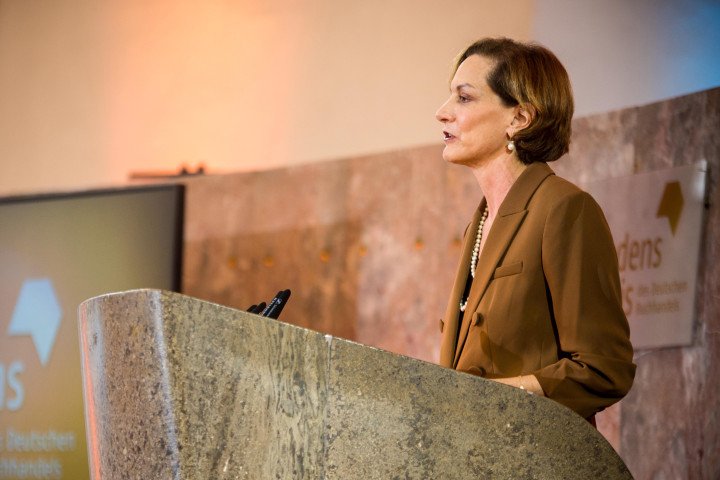

In July 2024, Pulitzer-winning author Anne Applebaum published her latest book ‘Autocracy Inc: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World’, where she explores the status quo for modern-day autocracies, the ways they operate and cooperate, as well as how this ‘interlinkedness’ can be the reason of their downfall. Below we explore the ideas outlined in her book in light of current political events.

It so happens that autocratic regimes rarely collapse without a warning. Instead, demise is born through the fissures of their foundation: systematic corruption, failed military campaigns, or protests, where voices grow louder despite repression. However, what we are witnessing today is unprecedented, as those cracks are not contained within national borders. They continue onwards, spreading through the international network of autocracies, with Russia—long thought to be the ‘guru’ in autocratic resilience—showing signs of systemic failure that has already rippled through its closest allies.

Autocracies 101: what are they, how they work and how they fall

What distinguishes today's authoritarian states from their 20th-century predecessors is their foundation in kleptocratic practice (from Hugo Chávez’s bolibourgeoisie to Vladimir Putin’s oligarchs) rather than ideological conviction. The go-to strategy of modern-day autocracies is to drape in nationalist narratives of historical and cultural exceptionalism, presenting themselves as defenders of a misunderstood nation's greatness. However, this rhetorical flourish proves insufficient when confronted with a population’s mounting socioeconomic dissatisfaction. In the words of a popular Ukrainian saying with a twist—you can’t spread doctrines on bread.

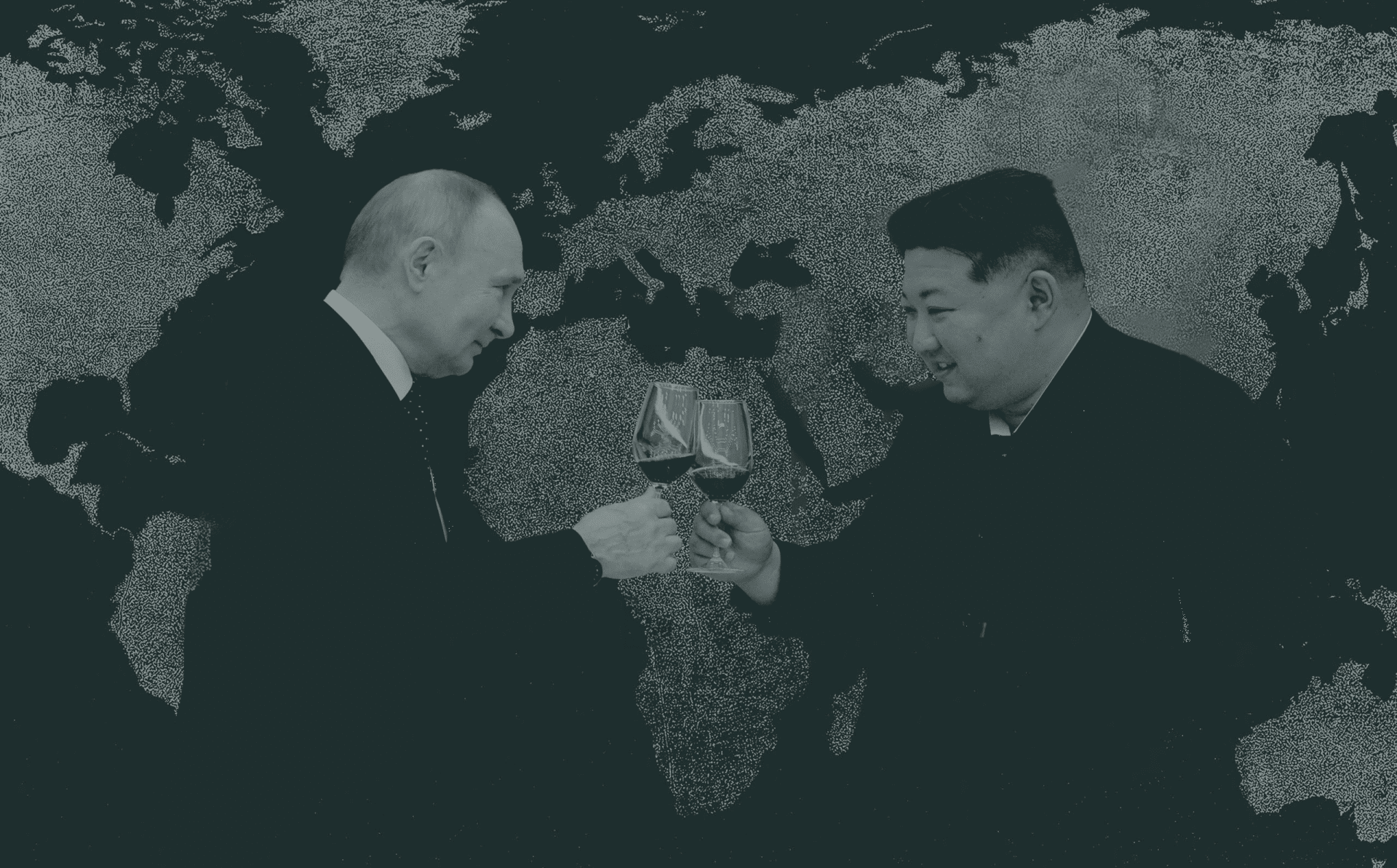

Anne Appleaum’s ‘Autocracy Inc.’ illuminates how authoritarian states have evolved beyond bilateral relations into complex ecosystems of mutual support. These networks operate on multiple levels, from military cooperation—for instance, between Iran, Russia, and North Korea, who gladly exchange weapons, ammunition, and soldiers—to more ‘subtle’ forms of collaboration in the fields of cybersecurity, bot farms, surveillance technology, sanction evasions and, of course, know-how methods of repression.

However, the very sophistication of this autocratic support network contains the seeds of its own destruction. The recent collapse of Assad's control in, where hundreds of thousands of protestors joined arms, toppling monuments dedicated to the regime, storming palaces and entering prisons—over a mere twelve days—provides a striking case study in the vulnerabilities of this system. Despite Syria's strategic importance to Russia's Middle Eastern ambitions, the regime crumbled when its autocratic allies found themselves consumed by their own crises: Russia mired in its prolonged war in, and invasion of, Ukraine, while Iran and their ally Hezbollah found themselves constrained by Israeli military pressure. It’s not surprising, therefore, that this interconnectedness might be their greatest vulnerability—such as a shift in the structure of a house of cards, where one falls, others subsequently follow, as autocratic systems can hold onto a precarious balance of external backing and internal repression only for so long. Syria’s scenario reveals a critical flaw in the system of autocratic rules worldwide: when multiple crises emerge simultaneously, ‘one for all and all for one’ quickly turns into ‘one for one, none for all,’ a desperate scramble for individual survival.

Perhaps most striking is just how countries like Russia attempt to stay afloat—by evolving into Frankensteinian hybrid regimes that maintain systematic oppression carrying the appearance of a democracy. In essence, autocracies are like Potemkin villages, theatrical in their execution, with their facades of elections, constitutions, laws, and rights together with civil institutions, masking what lurks behind the colorful, yet very flimsy construction—suppression, corruption, and a power structure designed only to benefit those at the very top. Therefore, when autocracies host elections, they are already with predetermined outcomes, when they do play court, they serve power rather than justice, when they claim freedom of speech or the press in their countries, they create manuals, construct boundaries, and act surprised when independent journalists ‘go missing’. This democratic mimicry, together with dithyrambs to ‘the greatest of cultures’, creates an illusion of normalcy, which helps distract both internal and external eyes. In fact, autocracies, like in the case of the Crimean ‘elections’ in 2016, love using democratic processes and procedures as cover-ups for their intrinsically repressive acts. The law works remarkably well if you can stretch and bend it to your will—one day you are committing war crimes and disregarding international conventions, and the other, you are urging others not to forget that the burden of proof is on the accuser, so come on now, chop chop, prove that we are the bad guys.

Although the revolution in Syria is a stark example of the fragility of autocratic alliances, equally telling signs of Russia’s struggle to maintain its geopolitical interests can be found in bordering Georgia, a nation tragically too well aware of the interest it poses to its neighbor (in 2008 Russia, under the pretense of ‘protecting’ South Ossetia and Abkhazia, launched an invasion of Georgia, occupying 20% of the country’s territory and, thus, starting the first European war of the 21st century).

For the past weeks, protests have been emerging all across the country in response to the alleged parliamentary victory of ‘Georgian Dream,’ a party heavily backed by billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, dubbed ‘Putin’s puppet.’ Millions of Georgians, together with their pro-EU president Salome Zourabichvili, have joined hands and taken their dissatisfaction to the streets of Tbilisi, installing barricades near governmental buildings and fighting off water cannons with modified firework launchers. Although these events eerily mirror Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity a mere decade prior, Moscow’s response was rather muted, unable to effectively intervene or shape events as it might have in the past.

This hesitation in supporting an aligned political force in a strategically vital neighbor represents a significant shift from the Russian historical pattern of swift intervention in its ‘near abroad’. Therefore, it is safe to assume that Russia’s action, or rather inaction, is not a sign of indifference or even an issue of resource allocation but rather a symptom of a regime’s extreme duress, as when everything around you is burning, it’s safe to assume that you are going to burn next.

So, what’s next?

“Everyone assumed that in a more open, interconnected world, democracy, and liberal ideas would spread to the autocratic states. Nobody imagined that autocracy and illiberalism would spread to the democratic world instead,” Anne Applebaum observes with pointed clarity in ‘Autocracy Inc.’ This insight gains a new sense of urgency as Yuval Noah Harari notes in ‘Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI,’ that the abundance of information doesn’t guarantee better-informed populations. In fact, the result can be the opposite—from the spread of half-truths and lies to radical and illiberal ideas.

The irony is thus: as ‘traditional’ autocracies show signs of structural weakness, their methods find new life in democracies. The challenge, therefore, is not only to celebrate the fall of existing autocratic regimes but to make sure that new ones are not constructed. This vigilance requires more than just opposing the obvious threats to democracy. It demands the strengthening of democratic institutions worldwide so that ‘Democracy Inc.’ can prevail.

-38556bf61e11af04a17331caebf42b61.jpeg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-661026077d315e894438b00c805411f4.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)