- Category

- World

Hungary Has Alternatives to Russian Energy, Yet It Clings to the Kremlin

Hungary persists in reliance on Russian gas, but viable alternatives exist—from LNG imports via Croatia to pipelines from Romania and Azerbaijan.

As the EU renews sanctions against Russia for another six months, Hungary’s government aims to bring Russian gas—the Kremlin’s war machine’s lifeline—back into the EU market. Hungary’s recent threats to veto EU sanctions against the Kremlin to get Russian gas back into the European market reignited tensions between Kyiv and Budapest.

Hungary’s bid to restore Russian gas

In 2024, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak claimed that due to rising prices for Russian oil, the share of oil and gas revenues in the Kremlin’s federal budget amounted to about 30%, quoted by Reuters. Russia's oil and gas revenues reportedly jumped by 26% in 2024 to $108 billion.

These funds are crucial for sustaining Russia’s war as the Kremlin plans to spend a third of its 2025 budget, the equivalent of $142 billion, on the military this year. In the meantime, the issue of Russian gas has become front and center of Hungary’s latest blackmail with the EU.

Ukraine ceased transmitting Russian gas on January 1, 2025, igniting outraged reactions from Hungary and Slovakia.

Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó soon after slammed Ukraine’s decision, accusing the country of destabilizing the EU’s economy.

"Although Ukraine is trying to join the EU as a candidate for membership, with its latest decision, it has once again put the European economy in a difficult situation," he wrote on Facebook.

The next day, he reacted to Ukrainian MPs' proposal to ban Russian oil and gas during martial law with a threatening post hinting at blocking the country’s potential membership.

"The reality is that in the EU, member states collectively and unanimously decide on the admission of new members,” Szijjártó wrote. “In other words, every member state has to vote in favor.”

Hungary reportedly demanded the EU put pressure on Ukraine to maintain Russian oil transit and reopen Russian gas transit.

It didn’t take long for Orbán to turn his back again to the EU after the latest January 27 vote on Russian sanctions. Right after the vote, he claimed that Hungary backed down from its veto because Hungary had received assurances from the EU’s executive arm regarding the resumption of gas transit through Ukraine.

"If the pledge is broken, then not only will we propose ending sanctions but we will end them," Orbán said.

Does Hungary need Russian gas?

Europe was Russia's largest natural gas customer, importing around 155 billion cubic meters annually—roughly 45% of its gas needs—from Russia before the 2022 full-scale invasion, providing billions to the Kremlin’s war coffers.

However, the share of Russia’s pipeline gas in EU imports dropped from over 40% in 2021 to about 8% in 2023. Russia accounted for less than 15% of total EU gas imports for pipeline and LNG combined, according to the EU Council.

Meanwhile, Hungary imported 82% of its natural gas and 41% of its oil from Russia in January-April 2024, according to a report published by capital consulting company FitchRatings.

Somehow, Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia, and Bulgaria secured an exemption from the EU oil embargo for pipeline deliveries to give the countries more time to find alternative suppliers. At the same time, Hungary and Slovakia can temporarily import Russian oil by sea routes in case of oil disruption through Ukraine.

When it comes to gas, Hungary and Slovakia tend to prefer when it’s Russian because it was sold at lower prices to get rid of the competition for a while, according to Michael Stoppard, chief strategist of global gas at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

For Stoppard, “Russia enjoys abundant low-cost gas that can theoretically be delivered cheaply to Europe. But it never sold its gas at cost — any more than Mideast oil is sold at cost,” Stoppard wrote for the Financial Times. “Russia sold its gas competitively but not cheaply. “

Another important point: the pipelines crossing Ukraine already exist, and there is no need to expand them to handle more imports in this huge network.

But it comes with a price of loyalty to the Kremlin, according to Mykhailo Honchar, president of the Center for Global Studies "Strategy XXI.”

“The problem is only that Orbán and [Robert] Fico seek to preserve corruption schemes,” Honchar told the Ukrainian outlet European Pravda. “Schemes under which oil from the Russian Federation was supplied to them at a special price, but this price already includes the loyalty of these politicians.”

Yet, Budapest has alternatives, starting with LNG.

Hungary has access to the Krk LNG terminal in Croatia, which is connected by the Adriatic Gas Corridor pipeline and allows LNG imports from countries like the US, Qatar, and Norway. The government would have to invest in expanding its pipeline infrastructure.

Budapest could also rely on neighboring European countries’ LNG terminals in Poland or Germany.

Hungary could also expand its imports from Romania, which has new offshore fields in the Black Sea. Infrastructure already exists, including the Arad-Szeged pipeline inaugurated in 2010, going from western Romania to Hungary, and its capacity is 4.5 billion cubic meters.

The project was launched amid the dispute between Russia and Ukraine over gas debt in 2008 that led to Russia cutting gas to Ukraine in 2008 and 2009, prompting EU leaders to try and lessen dependency on Russian gas, according to a report by the Jamestown Foundation.

By comparison, in 2023, Hungary consumed 8.7 billion cubic meters of natural gas.

Still, it means regional coordination through dialogue, and Orbán has been putting himself increasingly at odds with other European leaders over his pro-Russian stance.

Tension was reportedly palpable during an eve-of-summit dinner in February 2024, when Orbán tried to block €50 billion of aid to Ukraine to get back funds frozen over the Hungarian government’s disrespect for the rule of law, Reuters reported.

"We are to be 27, the whole community, and nobody is going to pay anybody for it (a deal). There will be no rewards, and nobody will be looking for rotten compromises," Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk said.

"The tensions were tangible during dinner yesterday, the talks tough...Everyone was angry at him [Orbán]," an unnamed diplomat said, while another concurred: "It reached boiling point,” reported Reuters.

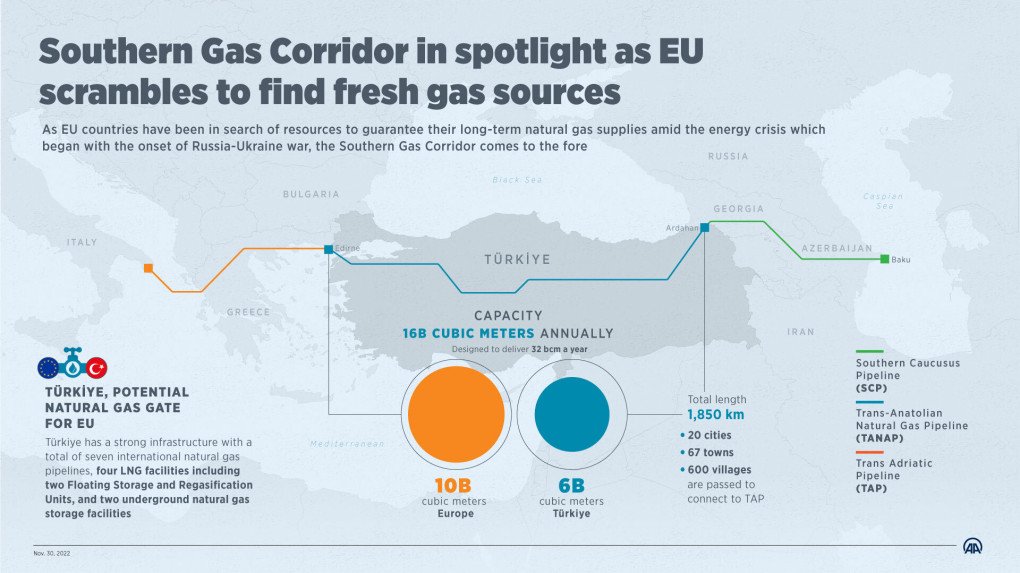

On the other hand, Hungary is also exploring importing gas from Azerbaijan via the Southern Gas Corridor, which brings Azeri gas to Europe through Türkiye. This alternative would also require investment, as Azerbaijan’s capacity to meet Hungary’s needs is limited.

Nuclear option

Nuclear power is also on the table to diversify the country’s energy consumption, but Hungary turned to Russia with its Paks II reactors’ contract signed in 2023, further tying the countries’ energy together despite Russia’s open hostility against Europe and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

In 2023, five EU member states operated 19 Russian-made nuclear reactors: six in Czechia, five in Slovakia, four in Hungary, two in Finland, and two in Bulgaria, according to a World Nuclear Industry Status report. In 2024, French companies imported the most low-enriched uranium from Russia, with about 30 tons imported directly to France, and a French-owned plant in Germany purchased up to 70 tons.

But countries like Finland, for instance, scrapped a €7 billion joint venture with Russian nuclear giant Rosatom after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. And in November 2024, the EU pledged to explore whether it should sever ties with Russia’s “full nuclear supply chain.”

Even with Russian-built reactors, Hungary could turn West and source nuclear fuel from non-Russian suppliers such as US company Westinghouse, which supplies nuclear fuel to Ukraine, Finland, and Czechia.

In November 2022, Finland’s electricity provider Fortum entered into a long-term partnership with Westinghouse to develop, license, and deliver fuel for its Loviisa plant, previously working with Russian fuel. Yet, Finland is still working with TVEL, a subsidiary of Russia’s Rosatom, and will honor its contract until 2030 to ensure stable fuel sources.

Switching fuel requires technical modifications and investment, but it would be key to diversify fuel sources instead of depending on the Kremlin. French company Framatome, a global nuclear fuel supplier, could also be a potential partner.

Hungary could also partner with Western nuclear technology providers to design alternative reactors, such as France's EDF, which provides reactors to France, the UK, and China; Westinghouse, which is already operating in the US and China; and South Korea’s KEPCO, which is already working in the United Arab Emirates.

Budapest could also develop Small Modular Reactors as an alternative to large nuclear reactors. The SMRs offer more flexibility and lower upfront costs. However, this technology is still in its early stages, with commercial deployment expected later in 2030 in countries like the US, Canada, and the UK.

Hungary keeps opposing it, according to an EU diplomat, granted anonymity, quoted by Politico.

“It’s clear that we need targeted restrictions on Russian nuclear, but this has proven controversial for Hungary because of their Paks power plant,” the diplomat said.

“We will not allow the plan to include nuclear energy into the sanctions to be implemented,” Orbán said back in November 2023.

Such deals serve as clear example of Hungary’s PM Orbán alignment with the Kremlin and efforts to leverage his position within the European Union. Portuguese MEP José Fernández highlighted this concern last year when Hungary obstructed aid to Ukraine.

“It is not acceptable for one EU prime minister, Viktor Orbán, to harm European citizens – the 450 million European citizens—with his blackmail and with his blockade tactics,” Fernandez said. “This political blackmail should never be rewarded.”

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-661026077d315e894438b00c805411f4.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)