- Category

- World

It’s (Not So) Quiet in the Arctic as Russian Espionage Heats Up

As tensions rise between Russia and the West, the Arctic has become a renewed front for covert operations and espionage, evoking the Cold War era.

Things are heating up in the Arctic and not just the temperature. Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, relations with Europe have gone cold. Russia’s western neighbors are shoring up their allegiances and joining NATO, with both Finland and Sweden casting aside years of neutrality.

Meddling and nuclear saber-rattling

Recent reports indicate that the United States has approved Ukraine’s use of long-range weapons to target military sites within Russia, a move widely seen as a direct response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s escalation involving North Korean troops in Russia’s war. Meanwhile, Putin has doubled down on his nuclear rhetoric, and on November 19 Reuters reported that the Russian leader updated his country’s nuclear doctrine saying “Aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) its allies on the part of any non-nuclear state with the participation or support of a nuclear state is considered as their joint attack.”

This is not the first time Putin has threatened NATO with nuclear escalation, nor will it likely be the last. Many view these threats as a tool used by Russia to delay the West and sew fear among Ukraine’s allies. Mikhail Ulyanov, one of the Kremlin’s top officials, even went so far as to say Finland would be the “first to suffer” if there’s “escalation.”

Meanwhile, Russia has escalated its spy operations in the region. Since the full-scale invasion, countries along Russia’s northwestern border have found themselves victims of covert, and even sometimes overt, hybrid attacks and meddling by Russia. These incidents range from minor espionage to the destruction of major infrastructure.

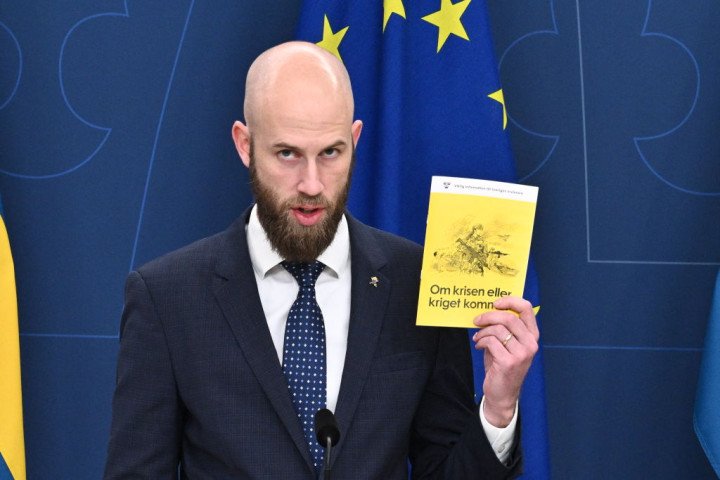

In November, the BBC reported that pamphlets outlining how to handle crisis situations, including mass evacuations, extreme weather, war, and other threats, were being distributed to civilians in countries like Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Norway’s pamphlet advises its citizens to have at least three days of non-perishable goods on hand, as well as iodine tablets, in case of a “nuclear incident.” While issuing such pamphlets is not necessarily new, reports claim that the pamphlets have nearly doubled in size since they were last issued in 2006.

The threat of Russia, real or perceived, underscores the importance of defeating Russia in Ukraine. To understand the nature of these fears we examine hotspots along Europe’s great white north and what each of the countries is doing to counter Russian interference.

Cyberattacks and spy ships

One of the primary targets for Russia’s hybrid attacks has been undersea cables. On November 19 CNN reported two severed cables in the Baltic Sea, one connecting Sweden and Lithuania and another connecting Finland and Germany,

The company’s spokesperson Audrius Stasiulaitis told CNN “We can confirm that the internet traffic disruption was not caused by equipment failure but by physical damage to the fiber optic cable.” The foreign ministers of Finland and Germany released a joint statement expressing deep concern about the severed cables and raised the possibility of “hybrid warfare.”

The warning came after a joint investigation by the public broadcasters of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland, which revealed in April 2023 that Russia was operating a fleet of suspected spy ships in Nordic waters, possibly as part of a program aimed at sabotaging underwater cables and wind farms in the region.

In addition to underwater cables, utility companies in Finland describe near-daily cyberattacks and even incidences of drones and suspicious individuals surveilling utility sites. Both Finland and Sweden have reported an uptick in suspicious activity by Russia in recent years with a spokesperson for Sweden’s Security Services saying, “We have seen a change in security-threatening actions in and against Sweden from Russian intelligence.”

The frontline of Arctic espionage

One of the places where such hybrid attacks and espionage are perhaps most prevalent is Norway’s Kirkenes, an isolated border town of just 3,500 residents along the Kola Peninsula. Mysterious fishing hawkers dock in the harbor and sailors on board carry handwritten seafarer passports. “You don’t actually know who is on board,” Johan Roaldsnes, the regional head of counterintelligence said. “If you do a deep dive on a bunch of sailors, you will eventually find somebody linked to the Northern Fleet.”

Russia’s Northern Fleet has made its home in the Barents Sea, just beyond the fjords of Kirkenes. Perhaps uncoincidentally since these fishing boats arrived in Kirkenes ports, transatlantic underwater communication cables between Europe and the Americas have been found inexplicably severed.

Near its border, Norwegian Counterintelligence says it has seen an uptick in the last decade of covert attacks ranging from cyber scams to catching tourists taking photos of sensitive defense infrastructure. “We’ve seen what we believe to be a continuous mapping of our critical infrastructure,” Roaldsnes told the New Yorker.

Moscow’s unconventional tactics

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, border towns like Kirkenes, whose industry was in the past built entirely off of trade with Russia, have now gone quiet. The closing of the border did not happen overnight though. It was only this past May that Norway officially closed its final border to Russian tourists, “The decision to tighten the entry rules is in line with the Norwegian approach of standing by allies and partners in the reactions against Russia’s illegal war of aggression against Ukraine,” Norway’s Justice and Public Security Minister, Emilie Enger Mehl, said.

The move was largely in response to a mysterious and inexplicable flood of refugees into Norway from Russia. At one refugee center in Vadsø, Norway 200 rooms were full of people from Afghanistan, Syria, and East Africa. They came in through Storksog, Russia, the only official Norweigan-Russian border crossing point at the time.

What made the sudden influx even more inexplicable was that in Storkskog, Russia entry into the town is only given with special permission by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), or a visa. These refugees were not only granted access to Storkskog but were also aware of a loophole that allowed them to cross the border. Since crossing on foot was prohibited, they resorted to crossing in large numbers using bicycles and wheelchairs.

Many of the refugees spoke Russian and some had even lived in Russia for several years. Norwegian border guards quickly began to understand the sudden influx was not a coincidence but a targeted attack. Roaldsnes soon found out that many of the refugees had been given intelligence tasks including taking selfies with and asking the names of, Norweigan border patrollers.

While these incidents hardly constitute a call to war, they do underscore an uncomfortable reality; Russia is continuously prodding and poking NATO to see how far it can go. Unfortunately in the case of Ukraine, it went several steps further.

Russia’s increased presence in the region

North of Kirkenes across the Bear Gap is Svalbard, a set of islands owned by Norway but outside the Schengen zone. On the island is Pyramiden, an abandoned former Soviet mining town that has been coined “Soviet Disneyland”. Russia has been making small but concerted efforts to reestablish itself in Svalbard, holding a military-style parade in Barentsburg which included 50 vehicles and a Mi-8 helicopter. Warlike activities have been forbidden on the island since a treaty was signed in 1920.

Russian officials have also erected an orthodox cross on the island and attached Soviet flags to cranes from which Norweigan flags once hung in the towns of Barentsburg and Pyramiden. Many believe Russia has set its sights on Svalbard to support its regional espionage efforts. Norwegian companies have even advised their employees to turn off their phones when entering Russian-controlled dwellings on the island.

In January 2022 an internet cable linking Svalbard to the mainland was intentionally cut. Perhaps uncoincidentally, a Russian fishing trawler passed over the cut site more than 100 times before the incident occurred.

Svalbard sits just above the Bear Gap, an important waterway connecting Svalbard to mainland Norway. Not far from the Bear Gap is the aforementioned Kola Peninsula, where Russia keeps its Northern Fleet. As a result of its war in Ukraine, Russian forces are spread thin and rely on the Northern Fleet as their main nuclear deterrence. Espionage activities in Svalbard are conducted to protect that fleet and acquire control of the Arctic, an area Russia views as its own.

The Arctic Council

Russia has the largest land and maritime claims in the Arctic. They control a significant portion of the Arctic coastline, and they have been investing heavily in infrastructure and military presence in the region. With global warming melting much of the Arctic’s ice caps, all-season maritime routes through the Arctic are now becoming a possibility and Russia plans to capitalize on them. These routes could replace the current southern trade route through the Suez Canal.

In 2022 Russia stopped making payments to the Arctic Council which is made up of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, and the United States. Its decision to stop paying into the council is widely seen as an assertion of its sovereignty and a response to what it perceives as Western interference in its interests in the Arctic. The US has accused Moscow of “militarizing” the Arctic, while the commander of Russia’s Northern Fleet told the BBC that NATO and US military activities in the region are “definitely” provocative and on a scale not seen since World War II.

Russia’s justification for its activities in the Arctic, citing NATO's presence, echoes the rationale it used for its invasion of Ukraine and marks a substantial shift. Even collaborative research in the Arctic has come to a standstill.

Since the Cold War, Arctic research has served as a key area of cooperation between the West and Russia. But now in light of the full-scale invasion, Russian scientists have to be more and more cautious about working with Western institutions for fear of retribution in their own country. “It is very similar to what it was like in the Soviet Union,” Dr. Romanovsky, who oversees a network of permafrost monitoring sites across Russia and Alaska, told the New York Times. “They have to be careful.”

Cold War in the Arctic

The Arctic Council itself was formed in 1996, at a time when Western relations with Russia were at an all-time high. As a theatre for much of the Cold War, the area continues to house defense infrastructure for the United States left over from that time.

During the Cold War, the US and Iceland signed an agreement allowing US troops to conduct air defense and surveillance in the North Atlantic to monitor Russian activity. However, in 2006, the US withdrew from this agreement due to a reduced threat and a shift in resources to its “War on Terror” in the Middle East. In 2020, the US returned to Iceland, investing approximately $38 million to revamp the former air base, including the construction of a new landing pad designed to withstand explosives.

Though Iceland is far from Russia, it plays a critical role in safeguarding Arctic waters. This importance has only grown since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with increased Russian submarine activity reported around Iceland. These waters are crucial for transatlantic communication, housing key undersea cables that link North America and Europe.

The buck stops here

As tensions between Russia and the West continue to rise, the Arctic has become a focal point for espionage and covert operations, reminiscent of Cold War dynamics. Nations like Norway, Finland, and Sweden are increasingly vigilant, reporting mysterious incidents and cyberattacks, while Russia appears to be testing NATO’s boundaries in the region. The renewed strategic importance of the Arctic, coupled with the activities of Russia’s Northern Fleet, and of course the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, has put northern Europe on high alert.

These worsening relations in the north, underscore the importance of Ukraine’s fight against Russia in the south where Russia is already testing NATO boundaries. Russian missiles have crossed into Polish airspace and naval mines threaten NATO members’ shores along the black sea—the alliance should take decisive action in Ukraine to signal it will not tolerate aggression in any of its regions. NATO has a choice to assert itself now or risk a potentially larger threat in the future. As the World War I saying goes, “Shall we be more tender with our dollars than with the lives of our sons?”

-fca37bf6b0e73483220d55f0816978cf.jpeg)

-27ef304a0bfb28cb4215e5deede4a665.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)