- Category

- Culture

Ukrainian Americans Were Divided by Faith and Identity—Until Russia Went to War

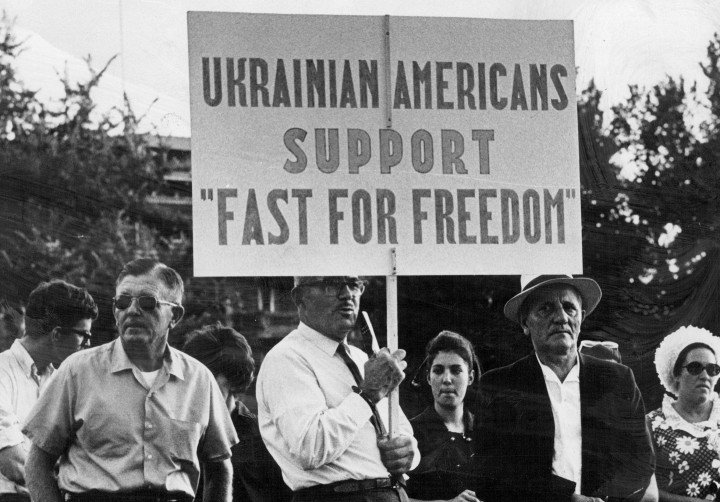

“Following the 2022 invasion, non-coordination was an impossibility.” When Russia launched its full-scale war against Ukraine, Ukrainian Americans mobilized with speed and passion. Churches held prayers, solidarity rallies erupted across cities, and diaspora leaders lobbied Congress for aid. But behind this surge of unity lies a complicated story. The Ukrainian diaspora in the United States has long been divided—by history, faith, and politics.

The Ukrainian community in America reflects Ukraine’s own fractured past. One wave of dissidents and immigrants, arriving largely in the 1980s, consisted of persecuted Jews and Protestant Christians who fled Soviet repression.

Today, most of the Protestant diaspora leans conservative and votes Republican, although parts of the older generation have shifted toward the Democrats. An older diaspora, rooted in pre–World War II migration, is more nationalist, often Greek Catholic or Orthodox, and historically concentrated in cities like New York and Chicago.

For decades, these groups had limited interaction. In the 1980s and beyond, “some associations, such as the Ukrainian Missionary and Bible Society, later as the Ukrainian Evangelical Baptist Convention in the USA, were as active as Greek-Catholic and Orthodox communities in spreading anti-communist information over the airwaves to the Soviet Union,” said Andrij Dobriansky, communications director of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. “However, the message always focused on their missionary work and evangelizing mission above all else.”

Dobriansky noted that, like many diasporas, the mission statements of Ukrainian organizations underwent reshaping after democracy was restored in Ukraine in the 1990s. Evangelical and Protestant denominations expanded their missions to bring the Word of God back to their homeland—but largely outside the Western-sponsored nation-building programs that engaged the older, mainline diaspora.

Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, however, forced a reckoning and, in many places, a tentative bridging of old divides.

We spoke with Ukrainian-American community leaders, scholars, and faith figures who have witnessed the diaspora’s transformation firsthand.

Finding its voice in Washington

Historically, Eastern European ethnic groups—including Ukrainians—have generally had limited influence over US foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Scholars and analysts point to a handful of notable exceptions, such as Zbigniew Brzeziński, but overall Ukrainian-American lobbying has not matched the clout of better-organized diasporas. By contrast, the Israeli and Armenian lobbies have often succeeded in exerting sustained influence on US policy in their regions.

“Eastern European lobbies, particularly Ukrainian ones, have been effective historically,” said John Vsetecka, assistant professor of history at Nova Southeastern University. “In the 1980s, Reagan courted Ukrainian-American voters by honoring the Ukrainian Helsinki Monitoring Group and supporting the US Commission on the Ukraine Famine.”

Part of the challenge lies in the legacy of Moscow’s information dominance. “We can safely assume that the Russian lobby has been quite strong, mostly because Russia appropriated the Soviet legacy and invested a lot into soft power, such as ‘making friends’ with the media and promoting Russian culture,” said Ilona Sologoub, an editor at Vox Ukraine.

“Eastern European lobbies have been effective in DC, but generally the Russian lobby has been the most effective,” said Vlad Bobrovnyk, head of advocacy at the Ukrainian Association of Washington State (UAWS). “Russians have set the tone in terms of post-Soviet states, and most American geopolitical understanding of the region was primarily from the Russian imperialist mindset until the 90s, and in many ways it still sets the tone today.”

“The diaspora is now more organized than other communities from grassroots efforts, but still doesn't compare to the political clout of the American Jewish or other similar communities with decades, if not centuries, of concentrated community building and advocacy efforts,” Bobrovnyk added.

Lukian Selskyi, editor in chief of the American-Ukrainian media outlet Vilni Media, put it more bluntly. “Ukraine’s interaction with the diaspora in the United States today looks contradictory,” he said. “On the one hand, there is a unique resource—millions of Americans who support Ukraine, hundreds of politicians from both parties ready to help, and hundreds of thousands of active Ukrainians, including many newcomers, capable of shaping public opinion and influencing policy.

However, Selskyi added that “there is still no systemic, long-term engagement with this environment, flexible enough to respond to daily challenges and stable enough not to depend on political changes within Ukraine.” In other words, Ukraine has a powerful diaspora, but no strategy to harness it.

According to the US Census Bureau, when ancestry data was first collected in 1980, about 730,000 Americans identified as having Ukrainian origins. That figure remained relatively stable throughout the 1980s but began to climb rapidly after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. By 2020, the number had surpassed one million.

Ukrainian veterans came to Minneapolis to receive new prostheses.

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) April 15, 2024

This is how they were met by the Ukrainian diaspora. pic.twitter.com/DMsC7LDi9E

Four waves of immigration

Ukrainian immigration to the United States came in four main waves: the early industrial migration before World War I, the interwar years, the post–World War II displaced persons, and the late Soviet/post-Soviet migration from 1989 onward. Each carried a distinct political, cultural, and religious profile.

The third wave—refugees after World War II—was more urbanized, educated, and fiercely nationalist. They established Ukrainian churches, schools, and institutions to preserve cultural identity while advocating for Ukraine’s independence.

By contrast, the later wave of the 1980s and 1990s, shaped by the Jackson-Vanik and Lautenberg Amendments, brought tens of thousands of persecuted religious minorities—Evangelicals, Baptists, Pentecostals, and Jews—to the US, particularly to Washington and Oregon.

These distinct migration waves brought not only different religious traditions but divergent understandings of what it means to be Ukrainian in America—differences that would shape the diaspora's politics for decades.

Opening the doors for Soviet refugees

In 1987, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced that victims of religious persecution could apply to emigrate under his glasnost reforms, which aimed to increase openness in government, media, and society. Two years later, the US Congress passed the Lautenberg Amendment, making religion the cornerstone of America’s Soviet refugee policy and extending protections to Evangelical Christians, among others. Together, these measures enabled roughly 500,000 Soviet evangelicals, including many Baptists and Pentecostals, to immigrate to the United States, either as refugees or through family reunification.

The New York Times reported in 2017 that “Evangelical Christians make up more than 90% of the current Lautenberg pool, the vast majority of them from Ukraine.” As a result, many Ukrainians who fled after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 joined existing Protestant communities in the United States. More than 270,000 Ukrainian refugees have come to the US since the invasion began. Many came through the Uniting for Ukraine program, which has brought thousands of newcomers into established local networks.

As Catherine Wanner, a professor of anthropology, history, and religious studies at Penn State, observed, “Highly favorable immigration policies have allowed nearly the entire membership of many Soviet congregations to relocate rapidly to the Pacific Northwest,” a movement that helped create the large Ukrainian Protestant communities.

“Most [Ukrainian] Protestants live on the West Coast,” said Oleh Wolowyna, director of the Center for Demographic and Socio-Economic Research of Ukrainians. In recent years, however, many Ukrainian Protestants have moved from the more liberal West Coast to conservative Republican states that better align with their values—places such as Ohio, Kentucky, and Texas.

Many of those communities in deep-red states remain largely disengaged from advocacy work, leaving a significant opportunity to build new political networks and strengthen Ukraine-focused outreach in regions where conservative leaders wield national influence. Still, it remains unclear how much that can change. For many Ukrainian Protestants, political activism takes a back seat to their spiritual mission.

The result is a diaspora that differs strikingly from Ukraine itself. In Ukraine, Greek Catholics and Orthodox are the dominant faiths, with Protestants comprising a small minority. In the US, Protestants—particularly Evangelicals—have become one of the fastest-growing immigrant groups from Ukraine.

Ukrainian-American faith and identity

Religious affiliation strongly shapes the diaspora’s political leanings, says Ukrainian-American researcher Anastasia Kharitonova-Gomez: “It is usually the main factor, though it's difficult to completely isolate faith from other influences. Evangelicals prioritize their religious identity over their cultural identity.”

Evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly vote Republican, aligning with the broader US evangelical movement. Catholics and Orthodox Ukrainians tend to lean conservative, albeit with more variation, while secular or non-evangelical Protestants tend to lean Democratic.

Catholics and Orthodox Ukrainians view faith as inseparable from cultural and ethnic identity—a pattern Kharitonova-Gomez attributed to those churches’ longer history in Ukraine and their linguistically specific traditions.

A divided diaspora

The divergence can complicate advocacy: Protestant congregations frequently worship in mixed Slavic churches where “being Ukrainian” is secondary to being Christian, while Catholic and Orthodox communities more often embed national identity in religious life. This difference in identity formation has deep historical roots.

“WWII migrants were political migrants with a strong sense of Ukrainian identity,” said Wolowyna. “Migrants after Ukraine’s independence were mainly economic migrants; Ukrainian identity was not a strong factor for many, if not the majority.”

These demographic shifts have reinforced the organizational divide. “The biggest difference between the Protestant diaspora and the Catholic or Orthodox communities is how disconnected they are from the broader Ukrainian community,” said Bobrovnyk. “Many large Protestant groups don’t participate in Ukrainian events or coordinate with us.”

That divide was also evident to George Davidiuk, a Ukrainian-American musician and Protestant leader, who recalled that “the post–World War II Ukrainian diaspora largely centered around their cultural events and dances called Zabava.” His church in Union, New Jersey, had only occasional contact with older diaspora groups—“we felt that they respected us, but our religious differences were too disparate for true interaction,” he said.

Bridging the divides

Russia’s war began to blur these distinctions. For decades, this division seemed permanent—a feature of diaspora life that neither side had much interest in changing. Then came February 24, 2022.

“When the war broke out in Ukraine, we all had a common goal—to advocate for Ukraine,” Davidiuk says. Wolowyna noted that Protestant leaders, once hesitant to engage politically, “have been more active in the Ukrainian community in recent years, especially as a reaction to Putin’s attack on Ukraine in 2014 and the invasion in 2022.”

Steven Moore, founder of the Ukraine Freedom Project, noted that Ukrainian Protestant networks have become deeply transnational. “Pavlo Unguryan is a Protestant pastor and former MP from Odesa who has built relationships with American Christian conservative leaders for a long time,” Moore said. “He has led American-style prayer breakfasts in Ukraine for years, and in June, the Office of the President sponsored his event in Kyiv, drawing more than a thousand faith leaders from around the world.”

Moore himself has worked extensively with Ukrainian Protestants in the United States. “I spoke in August at the last Turning Point USA Pastors Conference that Charlie Kirk would ever speak at,” he added. “A Ukrainian pastor from Sacramento and one from Virginia came with me, and a Ukrainian-American chaplain from Seattle was instrumental in one of the scenes from Donetsk in our film A Faith Under Siege.”

-d42bec5c53a6242e4c37a7f651cf78dc.png)

Davidiuk noted that a few years ago, the American National Prayer Breakfast, held each February in Washington, DC, attracted Unguryan, who brought several other Ukrainian politicians with him to attend. The following day, which was a Friday, this visit evolved into a broader gathering of Ukrainians from across all denominations meeting with the visiting officials from Ukraine.

This event became the foundation for what is now known as “Ukrainian Week,” centered around the annual National Prayer Breakfast in February, which brings together representatives from all denominations.

Ukraine’s advocacy challenge

The Russian invasion forced diaspora communities to work together in ways that once seemed unthinkable. “Following the 2022 invasion, non-coordination was an impossibility,” said Dobriansky. Evangelical pastors began lobbying alongside Catholic bishops, Jewish leaders, and secular activists.

Dobriansky said evangelical voices proved particularly effective on Capitol Hill, helping counter misinformation campaigns that threatened to block US aid packages in 2024. “The faith-based community was extremely helpful,” he said.

But tensions remain. Many evangelicals reject certain elements of traditional Ukrainian culture, such as folk rituals, alcohol, or festivals they consider pagan, which can make collaboration with older diaspora groups difficult. Still, the urgency of the war has fostered new habits of cooperation.

Yet even as grassroots cooperation has deepened, diaspora leaders warn that Ukraine's government has failed to capitalize on this moment. The energy exists; the strategic architecture to channel it does not.

Strategic gaps and missed opportunities

Selskyi pointed to what he sees as a larger flaw. “The Ukrainian-American community is a powerful lever of influence, yet state interaction with it remains unsystematic,” he said. “As a result, community energy generates many valuable initiatives, but they arise spontaneously and in different directions. Strengthening Ukraine’s positions in Congress and the American media can happen only when these efforts are aligned and scaled in a coherent way.”

He also warned of communication failures. “Ukrainian diplomacy in the US lacks strong channels and modern tools for engaging with public opinion,” he said. “This weak media presence is a decisive vulnerability, because the space is quickly occupied both by critics in the United States—domestic opponents who challenge Ukraine’s policies and support—and by outright enemies who seek to erase everything Ukrainian, with Russia at the forefront.”

Many leaders say the diaspora still misses obvious, high-value advocacy networks. Mariya Dmytriv-Kapeniak, president of the Illinois chapter of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) and a member of its national executive board, said it was “essential” to build stronger political connections in the United States. “Very few people of Ukrainian descent are running for Congress or serving in local government,” she said.

Dmytriv-Kapeniak pointed to untapped pockets of influence. In South Dakota, she said, a sizeable Ukrainian Protestant community maintains personal ties to Senator John Thune—“the kind of direct, personal connections that translate into real leverage on Capitol Hill.” She added that national groups, including the UCCA, have not engaged those communities meaningfully, a shortfall she called “a huge loss.”

Dmytriv-Kapeniak urged the UCCA to redeploy resources toward political advocacy rather than humanitarian fundraising. “Many NGOs can raise money for medical supplies or ambulances,” she said, “but only the UCCA is positioned to conduct high-level advocacy in Washington. Working ‘at the top of our license’ means taking on tasks that other organizations cannot.”

Emerging models and the road ahead

Newer organizations have also stepped into key advocacy roles. Razom for Ukraine, which emerged from the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, represents a younger and more professionalized model of diaspora engagement.

“Razom works closely with its partners in the civil society space,” said Mykola Murskyj, a director of advocacy at Razom, one of the lead sponsors for the Ukraine Action Summit. “Our policy experts have worked with the American Coalition for Ukraine [ACU] to identify the most impactful legislation that hundreds of Americans will advocate for when they come to Washington. We have partnered with Nova Ukraine to place advertisements in the New York Post, which is read closely by President Trump, spotlighting Russia’s abduction of Ukrainian children and the need to arm Ukraine.”

The October 2025 Ukraine Action Summit brought together more than 700 participants in Washington, DC. An “interfaith service led by religious leaders of various faiths and ethnic backgrounds” was held on October 26 during the summit, said Mira Rubin, a member of the ACU's board of directors.

When a Ukrainian BBC reporter stood up nervously to ask Trump a question, I think he expected the usual hostile media and so he called on her dismissively. By the end of their exchange, there was real empathy for her situation: Her raw emotions might be stronger than any logic— pic.twitter.com/4ePbz5UYH4

— JP Lindsley | Journalist (@JPLindsley) June 26, 2025

Igor Markov, a board member at Nova Ukraine, pointed to measurable results from coordinated diaspora advocacy. "Nova Ukraine's volunteers have been involved in advancing every Ukraine aid bill passed by Congress since 2022," he said. "Our coordination with other Ukrainian-American nonprofits helped secure passage of the National Security package in April 2024, including H.R. 8035 and H.R. 8038, which passed with strong bipartisan support—311-112 and 360-58 respectively—within a week of the Fourth Ukraine Action Summit."

Nova Ukraine has deliberately cultivated relationships across denominational lines, said Markov. "We've not experienced significant difficulties engaging with different branches of the Ukrainian diaspora based on religious affiliation," he said. "Since 2022, we've funded humanitarian projects at multiple religious organizations in Ukraine, including Protestant and Evangelical churches, Orthodox, and Greek-Catholic institutions. This approach allows us to deliver aid efficiently while working with trusted local partners, regardless of their religious affiliations."

Newer organizations reflect a more professional, modern approach to advocacy, distinct from the explicitly religious focus of many other community groups, says Bobrovnyk. “Because they don't have a religious focus, I think, they haven't always done the best job at actually connecting with the community and meeting them where they are in order to unify Ukrainian voices in the best interests of the community, which has led to some challenges.”

Still, the diaspora has made important progress in other areas. “The diaspora has greatly contributed to knowledge about Ukraine,” said Alexander Motyl, a professor of political science at Rutgers University-Newark. “The Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, Harriman, individual scholars, journalists, and writers have all had an impact on narratives, rhetoric, and, of course, knowledge. One cannot claim ignorance about Ukraine and Eastern Europe anymore.”

Kyiv’s priorities

Ukraine has made diaspora engagement a growing priority. “Supporting the diaspora is overseen by both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the newly established Ministry of Social Policy, Family, and Unity of Ukraine,” said Serhii Kuzan, chairman of the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center and former Ministry of Defense adviser. Since July 21, 2025, the new ministry has assumed responsibility for both diaspora and refugee support.

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has remained deeply active in this arena, even amid the war’s intensity. His office emphasizes what officials call “people’s diplomacy”: direct communication with Ukrainians abroad and their communities. Kuzan noted that such outreach has translated into steady support for Ukraine in countries like the United States and Canada, where diaspora activism is politically difficult for local leaders to ignore.

That activism was at its height in the first year of the Russian invasion, when rallies and grassroots lobbying surged across Western capitals. “Ordinary people reached out to their local congressmen, parliamentarians, and mayors,” Kuzan recalled. “This ensured strong support for Ukraine at every level.”

Today, the European Congress of Ukrainians remains central on the continent, while in the US, UCCA continues to serve as the diaspora’s flagship organization with Kyiv’s support, says Kuzan.

“This year marks the UCCA’s 85th anniversary,” said Michael Sawkiw Jr., the organization’s president. “Community activism has always been the UCCA’s strength, but the past 37 months of Russia’s full-scale invasion have pushed our networks to record levels of advocacy. Years of partnership-building with other diasporas, social and religious organizations allowed us to amplify our voice and ensure the United States responded with military aid, sanctions, and humanitarian support.”

Diaspora representatives are also woven into symbolic state occasions, such as Ukraine’s Independence Day, and play active roles in humanitarian, educational, and volunteer programs. Yet, officials in Kyiv acknowledge that activism has waned over time. “That makes it especially important,” Kuzan said, “to maintain constant dialogue and to express gratitude to those organizations and individuals who keep the world from forgetting about Ukraine."

Looking ahead

Whether this unity lasts beyond the war remains an open question. “I don’t think Ukrainian Protestants’ political activism will diminish,” said Eddie Priymak, a researcher on religion and politics in the Ukrainian diaspora. “But their focus will likely shift to US domestic issues, in line with the broader evangelical movement.”

“Each generation has a role to play in strengthening US-Ukrainian relations and in defending the Ukrainian nation,” Sawkiw said. “The battle for sustained support endures as Ukraine faces gripping new realities of Russian warfare.”

But whether this generation can transform crisis-driven cooperation into lasting institutional power—the kind that shapes US policy—remains the diaspora's defining test.

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-e704648019363ef9514cdd89b9bacc91.jpg)

-d3a157681c162cfaad134697053ff774.jpg)

-39ac5f6dfc009a14dbd02153363658d0.jpg)