- Category

- Perspectives

What Russia Is Really Doing to Protestants in Ukraine: An Interview with the Documentary Director

Gathering to pray could mean a knock at the door, a midnight raid, or never coming home—this is the new reality for Protestants in Ukrainian territories under Russian control.

The documentary A Faith Under Siege, which focuses on the lives of Christians, particularly Protestants and Evangelicals, in wartime Ukraine and their treatment by Russian forces, is set for global release soon. We spoke with the film’s director, Yaroslav Lodygin, about why this story needs to be told.

“At the heart of our film are the stories of two Americans who come to Ukraine,” says Lodygin. “They’re not connected in any way—they don’t even know each other.”

One story is of the film’s executive producer, Colby Barrett, a businessman and former US serviceman. Barrett saw a report on TV about the persecution of Evangelicals in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine. As an Evangelical himself, he was shocked.

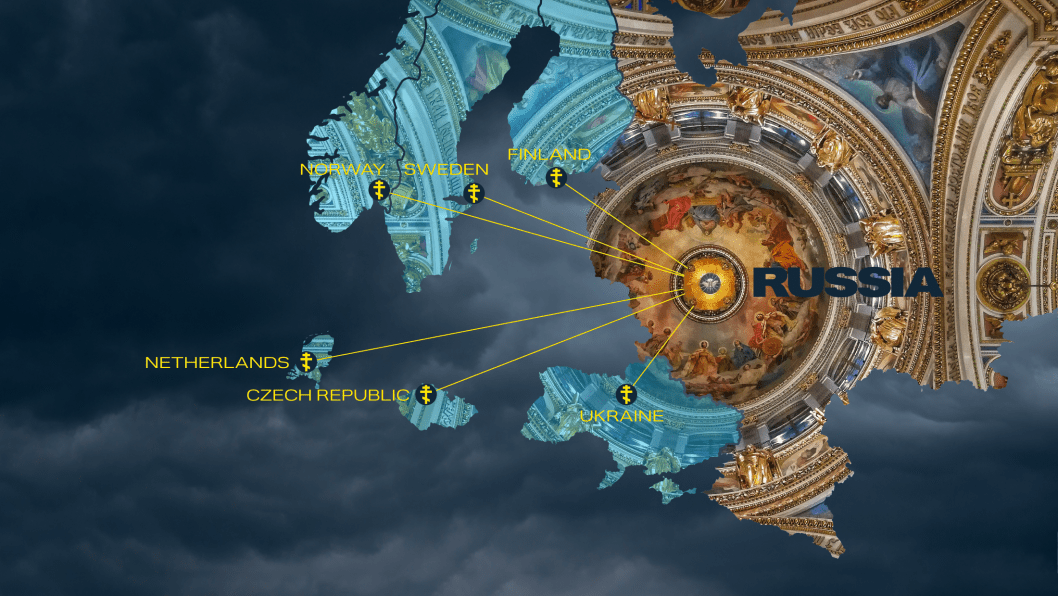

“Many people in the US still believe that Putin is some sort of defender of Christian values,” says Lodygin. “That belief is the product of sophisticated, well-funded disinformation and lobbying campaigns. It hit Colby so hard that he decided to come to Ukraine himself to see whether churches here are really under threat. His journey became the foundation of our film.”

The second protagonist, Christian Hickey, is also a US military veteran—a Navy SEAL and Evangelical missionary. He’s been in Ukraine since 2022, serving as both a missionary and a military trainer.

“So, we looked at Ukraine through the eyes of two American Christians—both former soldiers,” says Lodygin.

The power of faith

Protestants and Evangelicals are arguably the most active and united communities in Ukraine’s frontline zones, supporting not just fellow believers but anyone in need, says Lodygin.

They venture into places where international organizations are not willing to go.

“What drives them is their faith and a deep desire to protect human dignity,” says Lodygin.

In Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine, Protestants are often among the first to be targeted by the FSB. Russia’s security services typically seek out church leaders and begin applying pressure.

“The pastors we spoke with say that the first question asked during interrogations is almost always, ‘Who are your contacts in the SBU?’” says Lodygin. “For them, the church is viewed as part of the intelligence apparatus. They simply can’t believe that a pastor could not be an agent or liaison. Just like they don’t believe in independent journalism, or many other things we take for granted.”

One scene in the film shows Russian forces interrupting a worship service in Melitopol, in Ukraine’s southern Zaporizhzhia region, and arresting the pastor. They later searched his home, demanding that clergy under occupation preach what the Kremlin wants: tell their congregations to accept Russian passports and avoid protesting.

Melitopol once had more Protestant churches than Orthodox ones. The doors of the local house of prayer were smashed in with sledgehammers. A large cross in front of the church was chopped down and replaced with a Russian flag, and the building itself was confiscated and handed over to the ministry. Today, there isn’t a single Protestant church left in the city.

“They demand that pastors break the sanctity of confession and repeat what the confessors have told them,” says Lodygin. “To them, churches are just another tool for surveillance or propaganda.”

While filming, the crew uncovered documents from Stalin’s era, dating back to the 1930s, detailing how Baptist and Evangelical communities were to be punished. The repression continued up until the fall of the USSR. In many Baptist families, there’s a generational thread—if you’re a pastor, one of your children likely will be too.

“We saw the same names of pastors persecuted in the 1930s reappear in modern Russian documents on religious repression,” says Lodygin. “This shows a long, sustained campaign of targeting Evangelicals by state security structures.”

Pressure is also often applied through a pastor’s family, especially their children. “We collected extensive testimony on this,” says Lodygin.

Threats of conscription into the Russian military are common, even though many Evangelical churches strictly prohibit their members from taking up arms.

Protestants account for 34% of all documented cases of religious persecution, says UK journalist and writer Peter Pomerantsev in an article for Time magazine. One pastor in the piece captured the Russian mindset succinctly: “You are the American faith, the Americans are our enemies, the enemies must be destroyed.”

The US Commission on International Religious Freedom has designated Russia as one of the world’s “worst violators” of religious freedom, placing it alongside Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan.

Russia’s persecution of churches

“Russia claims to be a deeply Christian nation,” says Lodygin. “But we know the history of that ‘church’—the one Stalin created during World War II to morally control the army. Today, it still functions as a de facto arm of the KGB’s successors. Look at what it does: blessing missiles, tanks, weapons; calling for violence. How does any of that align with the teachings of Christ?”

Christians who do not belong to the Russian Orthodox Church face severe repression. “Many pastors have been forced to flee,” says Lodygin.

Jehovah’s Witnesses—though not Protestants—are completely banned in Russia. “Just last year, the only church of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine inside Russia was also shut down,” says Lodygin.

Putin has shut down every church in occupied Ukraine not controlled by the Kremlin. Believers who hold a Bible study in their home do so under the risk of imprisonment and torture. More than 2.5 million Ukrainian Christians live under these conditions in occupied Ukraine.

Before Easter, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy reported that at least 67 clergy members have been killed due to Russian aggression, and nearly 650 church buildings have been destroyed. Any form of dissent is dangerous.

“We documented a case of a girl who was sentenced to 20 years under terrorism charges just for saying something positive about Ukraine,” says Lodygin. “Many believers, including Protestants, now worship in secret in the Russian-occupied territories—gathering underground.”

Why these stories matter

Working on the film profoundly changed Lodygin’s own view of faith.

“I watched how these pastors and other religious leaders think and act. They operate in the hardest-hit places, and often they’re the only ones doing anything at all. Organized, effective action.”

While they provide essential aid like food, medical care, and evacuation support, their deeper impact is emotional and spiritual.

“They help people maintain their sense of self in the middle of all this horror,” he says.

“Perhaps that’s why Evangelical denominations are growing so rapidly in Ukraine today,” he adds. “Their churches are packed; they’re building spaces for thousands. They speak in plain language, they genuinely support people, and they create a sense of community. I see how important it is that they exist here, that there are so many of them, and that they’re so strong.”

Roughly 81% of Ukrainians identify as Christians. After decades of outreach by American missionaries, Ukraine is now home to more than a million Evangelical Christians. Baptists make up the country’s third-largest Christian denomination, following the Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches.

“Our film is also a hope—that evangelicals in the US and around the world, over 600 million of them, will see their brothers and sisters who look like them, who hold their services just like they do—and realize how simple it really is,” says Lodygin. “You don’t even need a deep political analysis. You don’t need to read thick history books. It’s absolutely clear who’s right and who’s wrong in this war. Just look at how each side treats Evangelicals, Protestants, and Christians in general.”

The film has already begun screening in the US, starting with private viewings. Film festivals, television broadcasts, and digital platforms are next.

“The most common reaction from Americans? ‘We had no idea. We didn’t know this was happening,” says Lodygin. “Many say they literally see themselves in Ukrainians—the same clothes, same rituals, same churches.”

Ukrainians, he notes, respond very differently.

“They watch it with different eyes,” says Lodygin. “‘Yes, we know,’ they say. ‘This is our reality.”

One of the film’s stories follows Serhii Haidarzhi from Odesa. In March 2024, he lost his wife and son in a Russian drone strike. What helped him survive the grief was his Evangelical community, where he remains an active member.

“I’ll never forget what he said: ‘No one promised us heaven on earth,’” says Lodygin. “And really—where did we get the idea that everything’s supposed to be perfect? That mindset seems to help him, and many other believers, endure.”

The film crew spent significant time with Serhii. Just as they were returning from Odesa, Russia struck Kryvyi Rih with a missile, killing many civilians. When Serhii learned that a fellow believer’s family had also been hit, he went there and spoke at the funeral.

“These are harrowing scenes, but it’s good that people around the world will see them,” says Lodygin. “Because they matter.”

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-886b3bf9b784dd9e80ce2881d3289ad8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)