- Category

- Perspectives

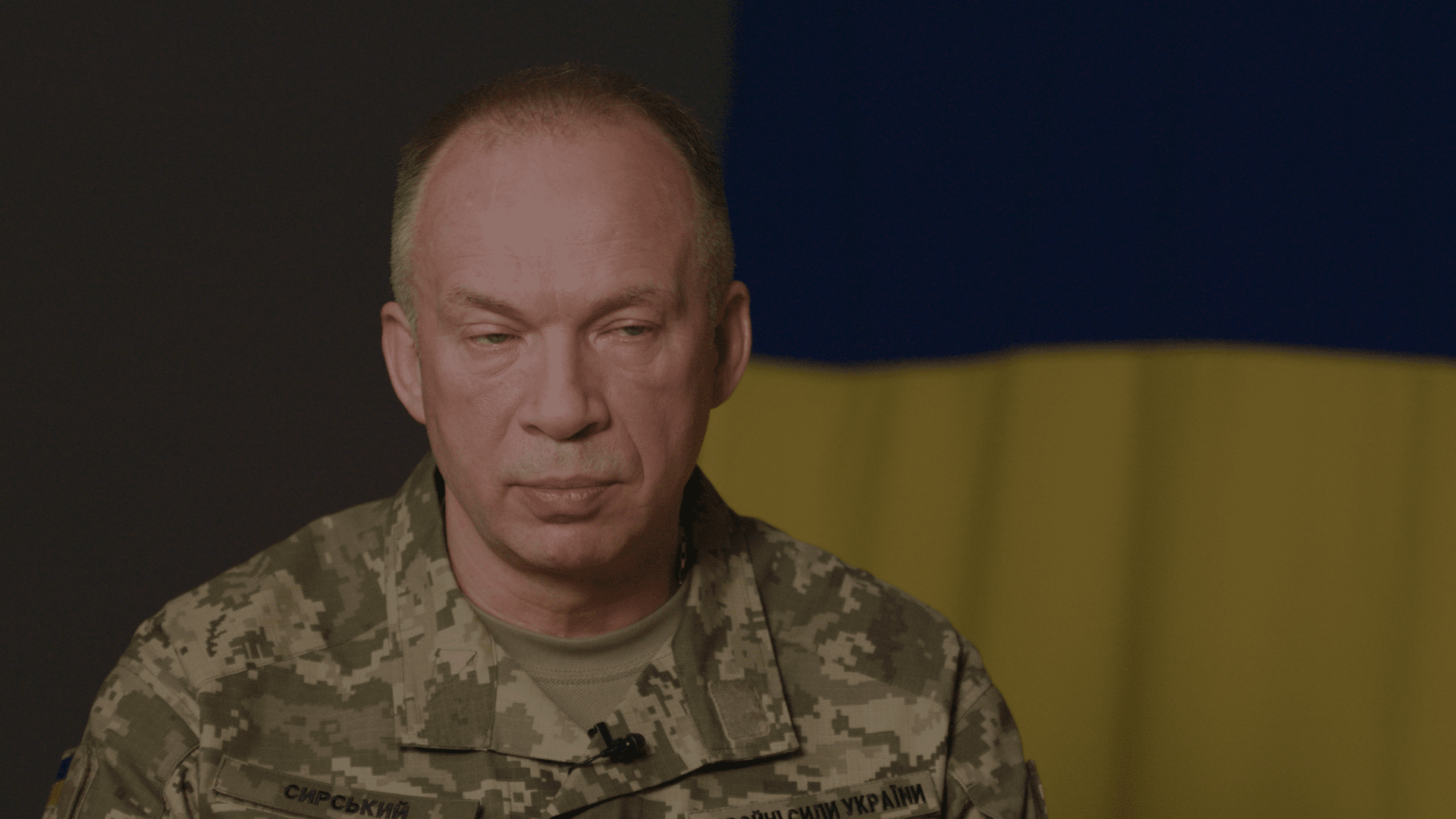

How Ukraine Took the Fight Into Russia: General Syrskyi Reconstructs War’s Boldest Operation—Kursk

With drone swarms and real-time satellite feeds, how do you hide an army? How do you cross a border that the enemy spent months fortifying? Ukraine found out in August 2024, when its forces entered Russia’s Kursk region and launched its offensive. This is how it happened.

For much of 2024, Ukraine was on the defensive. In Western military circles, a new consensus had taken hold: maneuver warfare was dead. Drones, satellites, and constant surveillance had frozen the battlefield. Large-scale offensives, it was said, now meant catastrophic losses. Then Ukrainian forces crossed into Russia’s Kursk region.

In less than three weeks, Ukrainian forces captured a vast stretch of Russian territory, forced Moscow to redeploy elite units from across the front, and derailed Russia’s entire summer campaign.

At the center of that decision was Ukraine’s Commander-in-Chief, General Oleksandr Syrskyi. We interviewed him to reconstruct how the operation unfolded.

What made the Kursk operation possible? What were the most important factors that contributed to this offensive?

First of all, the situation at the beginning of 2024 was really difficult. The enemy was replenishing its losses in manpower and equipment and launched an active offensive in Avdiivka. It was early in 2024. After the battle for Avdiivka ended, there was a certain period when the enemy began regrouping and preparing for a new offensive.

We also regrouped and replenished our forces. Measures were taken to stabilize the front. At the beginning of March 2024, intelligence started to indicate that the enemy was preparing a new offensive operation. Our reconnaissance provided conflicting data, but the enemy’s actions showed that, after the fighting, they began withdrawing some forces to the rear and regrouping and resupplying with equipment and machinery.

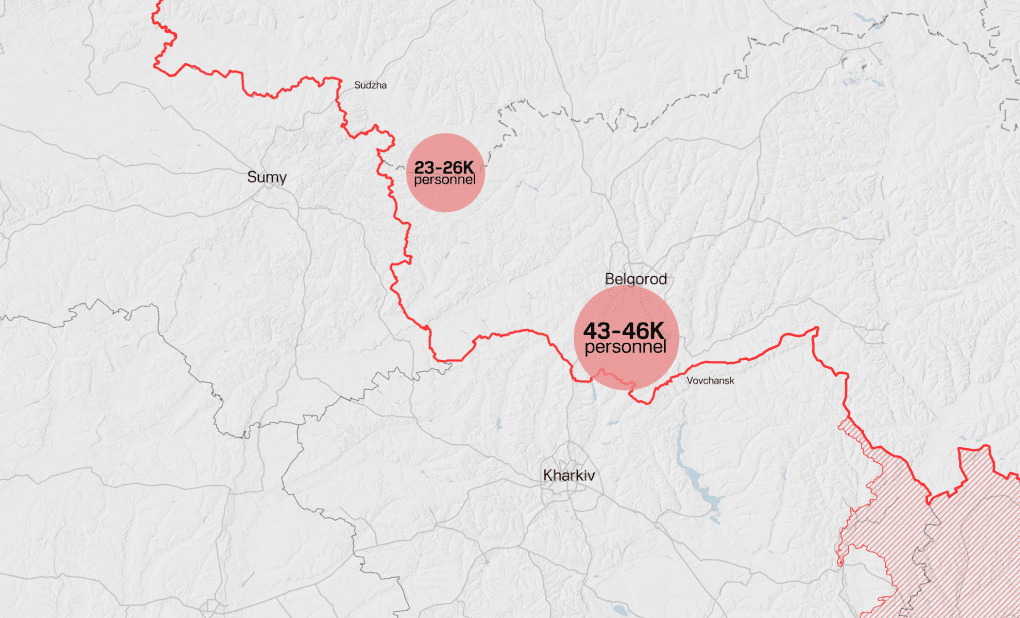

More and more often, reports indicated they were preparing for offensive operations toward Kharkiv and Sumy.

In response, we also prepared for a possible enemy offensive.

It was known that the enemy would attack in the Kharkiv direction, and by the end of April, they had built up a grouping of about 46,000 personnel in the Belgorod area, and about 23,000 in the Sumy direction. I made a decision—approved by the President of Ukraine, the Supreme Commander-in-Chief—based on the likelihood that the enemy would launch offensives in the Kharkiv and Sumy directions. So we, in order to preempt the enemy’s actions, deployed our troops directly to the border—from Vovchansk to the Sumy direction.

The enemy hadn’t finished preparing its forces. When they saw our units advancing to the border, the Russian military leadership decided to launch their offensive in Kharkiv with whatever forces they had.

The offensive began on May 10th.

In the border battles, the enemy became bogged down, took losses, and began gradually shifting troops from the Sumy direction. They suffered heavy losses with minimal success—advancing only 2 to 9 kilometers in the Kharkiv direction. After that, they achieved no further success there.

Given that, the Russian Federation decided to continue its offensive operations after finishing the preparation of other units by early June, aiming to break through our defenses and defeat our forces.

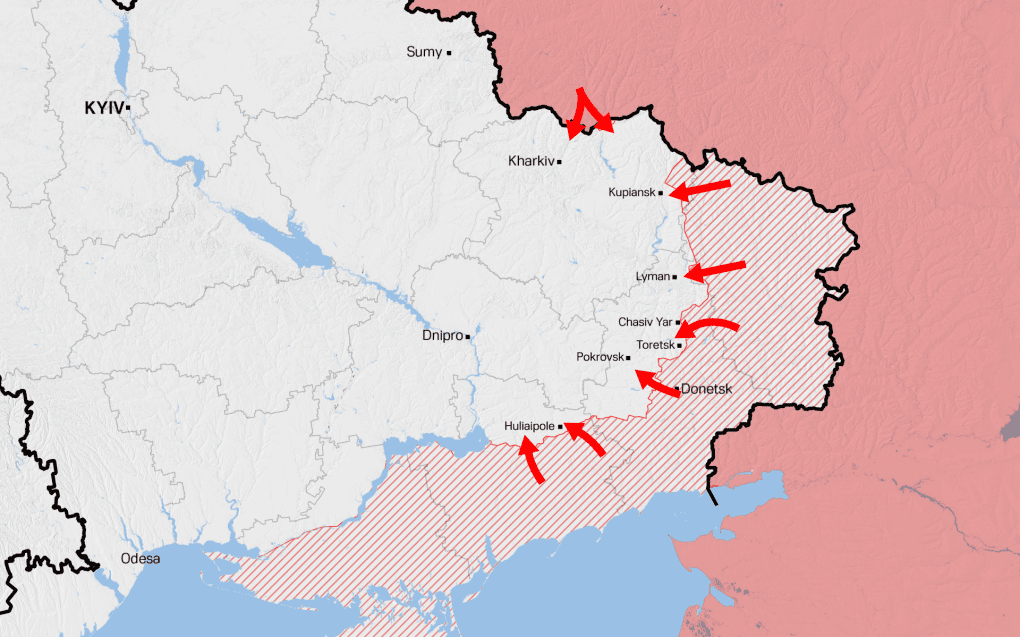

The situation at the beginning of June was very difficult for our troops. The enemy attacked along 12 operational directions—starting from Kharkiv, moving through Torske, near Bakhmut, Chasiv Yar, Pokrovsk, Zaporizhzhia, Kupiansk, Lyman—essentially across the whole front line.

The fighting was intense. The enemy had a numerical advantage of 5–6 times in key areas. The situation was really hard. Under these conditions, we had to make a decision—a decision that could radically change the course of the war and turn things in our favor, derailing the enemy’s plans.

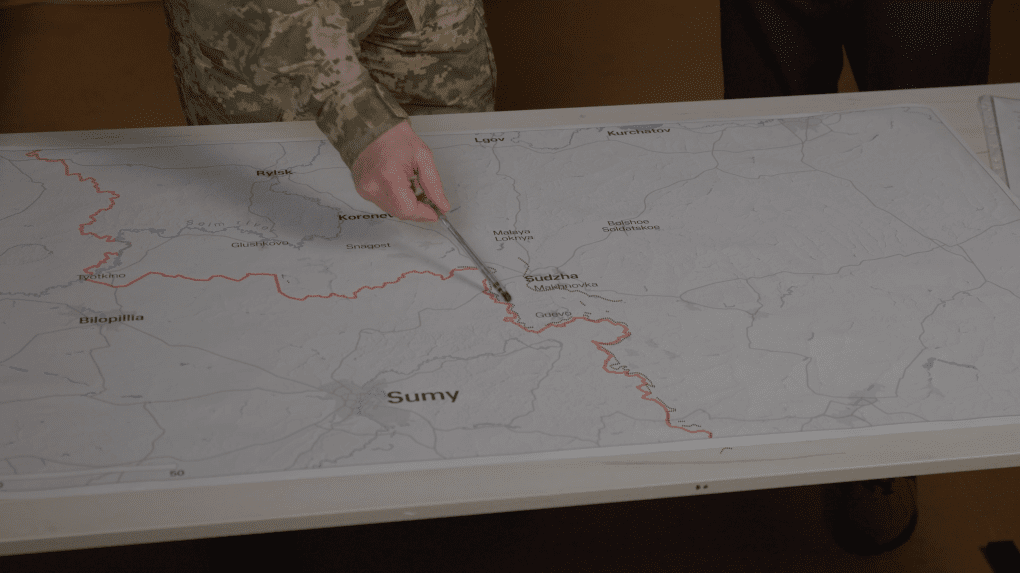

We conducted a thorough study of the enemy—their groupings, structures—to find weak points in their defense. Considering the ongoing threat of renewed offensives toward Kharkiv and especially Sumy, we didn’t ignore that axis. It turned out that Sumy was the weakest.

Operationally, because nearly all of the 23,000 troops had been moved to Kharkiv.

So we carried out preparation and regrouping under difficult conditions, despite the risk of being detected. Using the newly formed brigades, we rotated out airborne assault units.

Those airborne assault brigades were secretly withdrawn to staging areas where they were reinforced with personnel and underwent intensive offensive training.

We also pulled back two assault battalions stationed in the Sumy direction, which later played a decisive role in the offensive.

The preparation lasted two months.

The plan was approved by the President of Ukraine, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The main goal of the offensive was to decisively strike the enemy defending the border, penetrate deep into their territory, destroy their reserves, and inflict losses. This would allow us to seize the initiative, force them to halt offensives elsewhere, and give us time to stabilize the front.

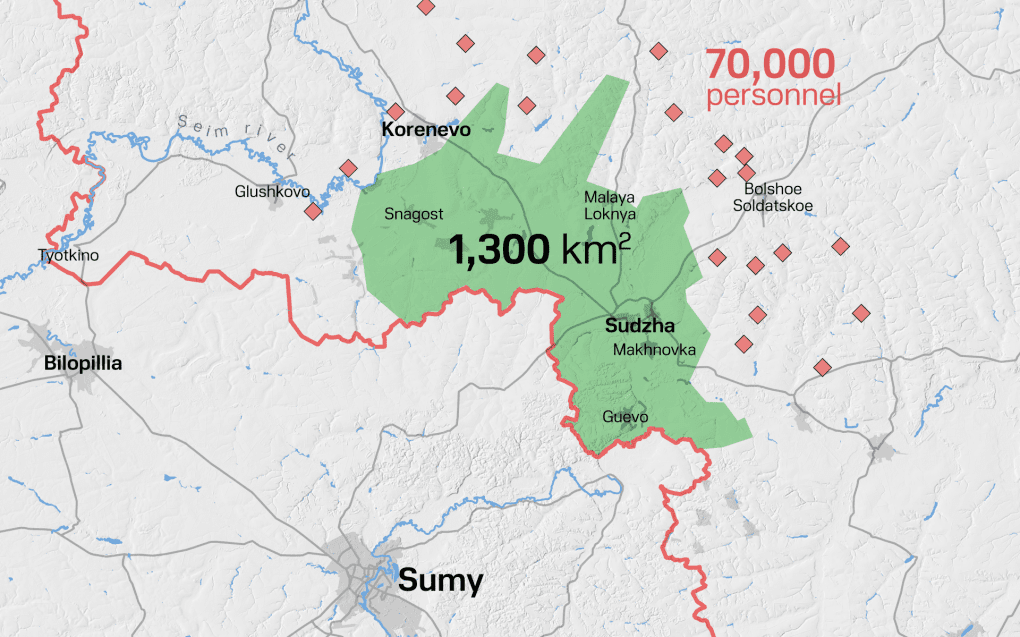

The operation began on the 6th (of August—ed.). In just three weeks, we captured almost 1,300 square kilometers. The enemy retreated along the entire front. To stabilize the situation, they moved troops from other areas—except Pokrovsk, which remained active.

The enemy concentrated about 70,000 personnel in the Kursk direction—including their best: airborne forces, marines, special operations, and elite mechanized units.

That’s how we disrupted their 2024 summer campaign, prevented our forces from being overwhelmed, and forced the enemy to abandon their plans and adjust strategy.

We’ve heard some things about the preparation for Operation Seneca. What was it and what was its goal?

Every major military operation includes special missions. I can’t go into all the details—maybe after the war—but we carried out a comprehensive set of deception measures to mislead the enemy, hide our actions, divert attention from our main direction, and simulate troop movements, especially when relocating units.

We also carried out special actions on the territory held by the enemy.

Together, all these actions produced a positive result and enabled the successful ground phase of the operation.

Which key positions did Ukrainian forces hold and capture—and why was defending them so difficult?

The biggest challenge was assembling the offensive grouping in secrecy. We had to do this without being detected by drones or satellite surveillance.

All units stayed far from Sumy until just ten days before the operation. They were hidden in forested areas, using terrain features like ravines and dense tree cover.

This allowed us to concentrate forces in secret.

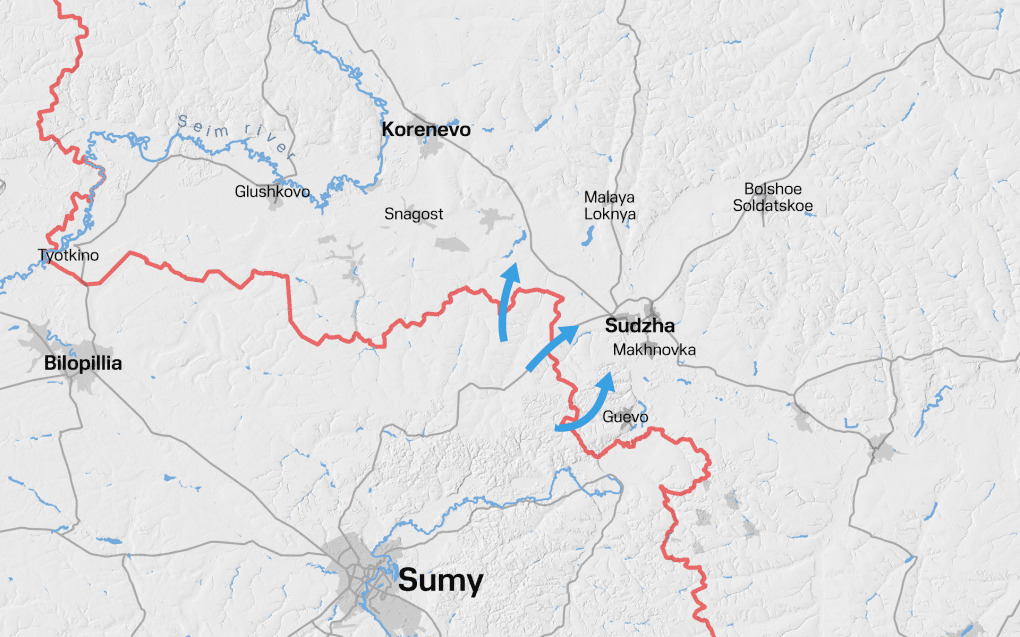

Crossing the state border was the first major obstacle. The Russians had created a fortified line—trenches, mines, “dragon’s teeth,” and other obstacles, stretching in multiple layers.

There were reinforced bunkers for infantry—entire fortified zones with concrete shelters where troops were stationed underground and fully equipped for prolonged defense.

This border fortification caused delays, but our assault units bravely breached the defenses under fire and created passages for the main forces to advance.

The first key town we took was Sudzha. A separate brigade was assigned to it. Other units advanced deep, avoiding engagements where possible, bypassing the enemy. This left the enemy behind our lines and forced them to retreat.

Though resistance was fierce, our planning and morale prevailed. Early victories motivated the troops. One goal of this operation was to inspire soldiers with the idea of advancing.

Within three weeks, we had captured nearly 1,300 square kilometers.

Were any specific brigades or battalions decisive in the Kursk operation?

Several brigades—mechanized and airborne assault—were directly involved in the Kursk operation.

The decisive role was played by the 82nd, 80th, and 95th Airborne Assault Brigades, which formed the core of the offensive force. Also, two assault battalions that were later expanded into regiments—the 225th Assault Battalion and the 33rd Battalion. They broke through defenses, cleared paths, and enabled the main forces to advance. In addition, there were mechanized brigades involved, which formed a defensive grouping.

Their role changed in the later stages of the operation.

Toward the end of the operation, what challenges were there?

Like all operations, a secure and organized withdrawal was essential to avoid personnel losses. We had designated staging lines, vanguards, and rear guards, and we executed the withdrawal in an organized fashion.

In mid-December, videos emerged appearing to show North Korean soldiers in the Kursk region. What can you say about their deployment, timing, and tactics? Did their presence have any measurable impact on the operation?

Despite having nearly 70,000 elite troops, the Russians couldn’t succeed. So they brought in North Korean troops—four brigades, about 12,000 soldiers.

They trained in Russian camps for a month, then were sent to the front.

They were mostly under 30, highly motivated, ideologically committed, and followed orders unquestioningly—almost robotically.

They used Soviet tactics—attacking in platoons or companies, ignoring casualties, fighting to the last man. It was shocking because the Russian army doesn’t fight that way.

They suffered heavy losses—over 4,000 dead. One brigade was completely wiped out, and the others were rendered combat-ineffective. After that, their active role ended.

They were retrained, equipped with Russian gear, and used to reinforce Russian units in subsequent operations.

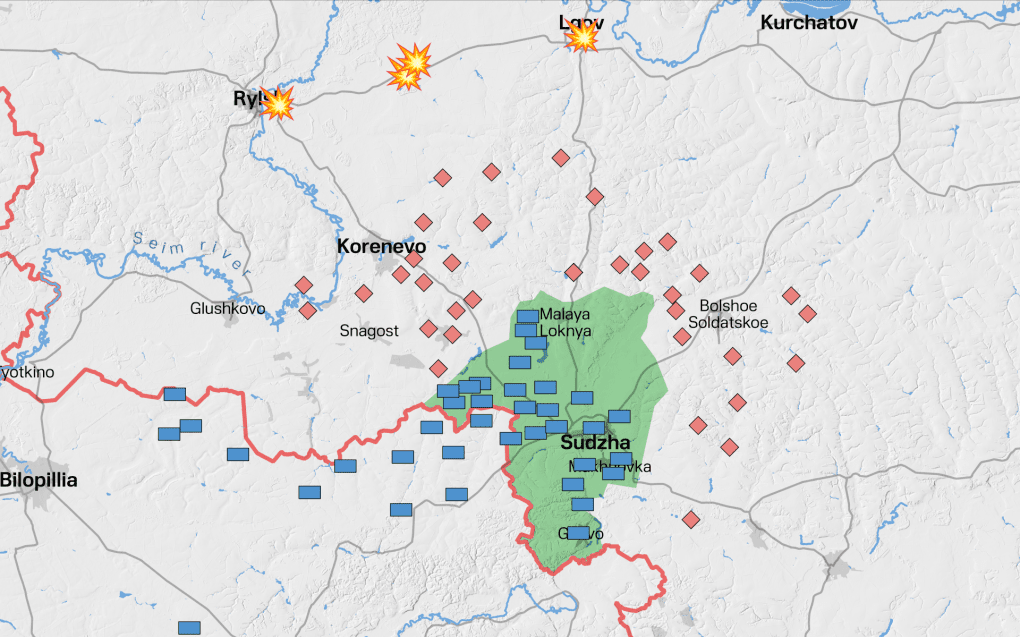

In November 2024, international partners allowed Ukraine to strike Russian territory with long-range weapons like ATACMS and Storm Shadow. Ukraine was able to strike high-value military targets deeper behind Russian lines. How did this change operations, and will this capability be needed in the future?

Our partners saw how Russia used all kinds of missile weapons against us, including fiber-optic-controlled drones that our electronic warfare couldn’t counter.

In the Kursk direction, 50% of all guided bombs were used. Our positions were bombed daily. Russia also regularly attacked Kharkiv and Sumy with S-300 and Iskander missiles, endangering civilians.

Eventually, the US government allowed us to use our own long-range weapons—up to 700 kilometers—against military targets in Russia.

In March, reports and videos emerged of Russian troops attempting to enter Sudzha via an oil pipeline. What can you say about this Operation Stream, and how effective was it from a military standpoint?

It helped Russian troops to some extent. But the pipeline itself didn’t play a decisive role. It allowed two to three enemy companies to land near Sudzha.

But the real issue was the massive bombings and fiber-optic drones. The entire area beyond Sudzha was under attack and under control.

The enemy focused on destroying our logistics capabilities.

Why was this operation important, and what did it give Ukraine at both the strategic and operational levels?

This operation was truly unique because it was the first to be conducted on the territory of the Russian Federation. Something like this hadn’t happened in nearly 400 years.

But that wasn’t the main reason we carried it out. As I’ve already said, the primary goal of the operation was to eliminate the possibility of a Russian offensive operation into the Sumy region. That is, for almost a year, the region and its residents were spared the horrors of Russian occupation.

When we launched the offensive operation in the Kursk region, we eliminated the threat by defeating the forces preparing for the offensive. By conducting these offensive actions, we created our own buffer zone.

For eight months, Russian forces were striking their own territory, bombing their own settlements. They effectively turned the entire border area of the Kursk region into total ruins.

The offensive in the Kursk direction also changed the course of the war. It disrupted the enemy’s plans and prevented the destruction of our forces in other areas, as the Russians were forced to switch to defense and redeploy troops from other fronts, which significantly weakened them. As I’ve already mentioned, troops were redeployed from almost all directions except Pokrovsk.

This operation greatly motivated our troops. They saw that after a year of defensive fighting, we could go on the offensive again. We demonstrated that we could hit the enemy, even when many theorists claimed that a modern offensive of this kind was impossible.

We showed that even under conditions of drone, satellite, and air dominance, we could secretly form offensive groupings and conduct offensive operations.

We are capable of conducting deep operations. To stop us, the Russian army must build defenses that are much larger in number than our offensive units. Our losses were lower than those of the enemy, even though we were attacking and they were defending. This encouraged our soldiers to continue offensive actions. The effectiveness of our airborne assault forces was confirmed.

The first two battalions showed high performance, which made it possible to scale them into regiments and create a new branch of forces that proved to be highly effective.

These structured forces became the foundation for breaking through the enemy’s defenses. Their speed and coordination helped normalize the situation. The key role of the airborne assault troops was also confirmed, as they operated closely with assault units.

Although assault and airborne assault troops have similar names, their missions differ, but they must operate together. That’s what ensures their effectiveness.

These are the main reasons and lessons we learned from the Kursk operation.

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

As a general, you’re responsible for the military part, not the political one. But after capturing this territory, did you think Russia might agree to negotiations, or was it clear they would continue fighting?

Maybe that could have happened. That’s exactly why it was important for the Russian leadership to push us out of Russian Federation territory.

This process went on for nearly eight months, and I want to note that our units are still present on Russian territory. This gives us new opportunities to conduct operations and combat actions inside the Russian Federation, while the Russian forces are forced to hold a significant contingent to counter us.

How would you describe the current situation in Sumy and the border regions?

Due to the use of North Korean ammunition and the creation of a numerical and resource advantage, by the end of the Kursk operation, the number of Russian troops had reached up to 93,000 soldiers.

A huge amount of weaponry, equipment, and strike drones was concentrated in this direction.

Operators of the Unmanned Systems Forces eliminated four North Korean “Koksan” self-propelled artillery systems.

— 🇺🇦 Unmanned Systems Forces (@usf_army) September 30, 2025

Fighters from the 412th Nemesis Regiment of the USF identified and struck the Koksan self-propelled artillery units in Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia regions. One of the… pic.twitter.com/txe1Kr0wBA

This allowed them to conduct successful offensive actions gradually. We did not intend to stay permanently on Russian Federation territory—this operation was temporary, aimed at achieving specific goals. Once the main tasks were accomplished.

The Russian grouping significantly outnumbered us. To avoid unnecessary losses, we gradually withdrew to the border.

We established positions along the border between Sumy and Kursk regions. Russian forces managed to advance 10–12 kilometers into our territory, but they were stopped. Then we regrouped and launched a counteroffensive, stabilizing the situation.

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

Active efforts are now underway to completely push the enemy out.

Russian forces are trying to hold on to the small portion near the border that they still occupy and are conducting counteroffensive actions.

So, we can say the situation has stabilized, though it remains tense.

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-7e242083f5785997129e0d20886add10.jpg)