- Category

- Latest news

How NATO’s 1980s Missile Gamble Paid Off—and Why It Could Work Against Putin Today

A Cold War-era missile deployment that helped push the Soviet Union to the negotiating table may hold key lessons for the United States and NATO today. As Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine grinds on, experts are urging Washington to consider similarly bold moves to restore deterrence in Europe, including the visible forward deployment of nuclear-capable weapons.

A historic Cold War episode—the NATO deployment of nuclear-armed cruise and ballistic missiles in Europe—offers a powerful blueprint for how the United States can reassert its leadership and deter Kremlin aggression in the current security environment, according to a new analysis from the RAND Corporation .

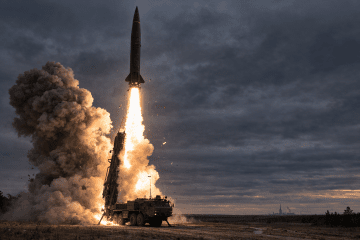

In 1979, NATO made the collective decision to deploy 464 ground-launched BGM-109G Gryphon cruise missiles and Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Europe.

Delaying deployment, timing for impact: lessons from the 1980s

While the decision was made at the end of the 1970s, the actual deployment only began in 1984, once the timing aligned with the broader geopolitical situation.

Despite the delay, the move proved highly effective in signaling Western resolve and deterring the Soviet Union. And that, the RAND analysis argues, is exactly the kind of show of force the US should consider now.

Time January 31, 1983 - Nuclear Poker

— Casillic (@Casillic) December 8, 2022

The stakes get higher and higher cover page Pershing II Missile launch pic.twitter.com/npDL7Y0N3a

The paper, authored by veteran arms control diplomat William Courtney, stresses that the Cold War-era missile deployments were a deliberately demonstrative act.

The goal was for the Kremlin to clearly see that Europe was “saturated” with American nuclear missiles. Surface ships armed with sea-based Tomahawks—while still dangerous—wouldn’t have had the same visual or psychological impact.

Because the objective was to send a strong, visible signal of intent, NATO’s decision in 1979 focused on the symbolic value of land-based nuclear assets stationed in Europe.

The move countered the Soviet Union’s own deployments of RSD-10 “Pioneer” intermediate-range ballistic missiles and set the stage for strategic arms talks.

The RSD-10 Pioneer (SS-20 Saber), intermediate-range ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead pic.twitter.com/vfgBv6he23

— Tweet Militer (@tweetmiliter) December 28, 2015

That firm stance ultimately led to a major diplomatic breakthrough: the 1987 INF Treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty), in which the US and the USSR agreed to eliminate an entire category of nuclear missiles from Europe.

The agreement is widely regarded as one of the key milestones that contributed to the end of the Cold War.

From Pershing II to SLCM-N: modern tools for strategic messaging

Courtney draws a clear parallel to the present. The US, he argues, should act just as decisively as it did in the 1980s to reestablish credible nuclear deterrence in Europe. Doing so would reinforce Washington’s leadership role within NATO and across the continent.

He also notes that while the US can rely on its existing nuclear delivery systems, it should also invest in next-generation capabilities, such as the sea-launched cruise missile project known as the SLCM-N.

But he cautions that for now, the US lacks a deployable nuclear version of the Tomahawk, even if there’s political interest in reviving it.

Earlier, Russia deployed autonomous launchers from its RS-24 Yars mobile intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) system to combat patrol routes as part of a scheduled readiness exercise in the Yoshkar-Ola missile formation, located in the Mari El Republic.

-c439b7bd9030ecf9d5a4287dc361ba31.jpg)

-72b63a4e0c8c475ad81fe3eed3f63729.jpeg)