- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Meet the Wild Ukrainian Wrestling Scene Where Bruises, Beer, and Air Raids Collide

-4dcc1994829c4e60ebddd2fa1f8e601b.jpg)

You're probably not aware of it—but Ukraine has wrestling. And it’s compelling even for those who’ve never been fans of the genre. We attended one of its spring events—and witnessed a one-of-a-kind spectacle taking place, despite Russia’s war.

John Cena turns heel . Sheamus makes a comeback. Cody Rhodes readies for revenge at WrestleMania. If you’ve ever glanced at wrestling, these phrases likely sound familiar.

But how about this:

In the vast hall of an old Kyiv factory, between air raid sirens, a Ukrainian soldier becomes the top contender for the Extreme World Championship.

This is the story from the Ukrainian Wrestling Arena (UWA), a promotion born in Odesa nearly a decade ago. Since then, it's held over 80 shows. In 2023, it moved to the capital.

In the early days, enthusiasts tossed each other around rings set up at biker festivals or inside cultural centers. Sometimes, in the background, you’d catch a glimpse of decorative flowers—pretty but wildly out of place in a wrestling scene. And for the record, in the final match of the first-ever Odesa Wrestling Cup, Big Van Markus defeated Pepsi Kolya.

Since then, Ukrainian wrestling has become much more professional and spectacular. Now it is a fairly large-scale and well-thought-out show, attended by hundreds of people.

Ukraine’s wrestler Pepsi Kolya, by the way, is still active. His nickname is a mash-up of the global brand and Kolya, a popular Ukrainian name akin to Nick. A few hours before the show, he paces thoughtfully backstage in white-and-red pants. For our photo, he throws on a cloak and sunglasses—completing the look.

Nearby, another wrestler, Dustin “DieHard” Lee, sits on a couch, carefully prepping his gear — sticking thumbtacks into a pair of nunchucks. I check — they’re real, and they’re sharp.

Dustin Lee is not a ring name. Born in Ohio and raised in Indianapolis, Indiana, he worked in design and social media. Dustin came to Ukraine recently — at first just for three weeks, driven by a desire to see for himself what he’d been reading about in the news. But he liked it so much he stayed. He met a girl, started learning Ukrainian on his own, and now teaches English locally.

Meanwhile, in the main hall—a bar called Porter—wrestlers are warming up and rehearsing moves. If you’re curious, the beer goes for about $1.50 for a half-liter (with around ten options on tap), burgers run $5, and tequila shots start at $2.

But the towering industrial architecture betrays another story. This space is part of a massive factory complex built in Kyiv over 150 years ago. It once churned out ships and bridges — now, it forges stars of Ukrainian wrestling.

Inside the ring, wrestlers practice high-impact moves. Just beside the audience seating, two 100-kilogram fighters toss each other around with impressive zeal. One — Miller — repeatedly slams Andrii Vedmid’s head into a metal railing. After the final blow, Vedmid calmly remarks, “That one was a bit too much,” then hurls Miller over the same railing. A waitress watches as over 100 kilos of muscle in tight pants crash at her feet. She nods, impressed, and simply says, “Wow.”

As the hall begins to fill, the wrestlers head backstage. Some chat, others watch clips from Western shows, and a few keep training. Dustin finishes modding his bloodletting nunchucks and begins attaching thumbtacks to his shin guards. I ask how he got into Ukrainian wrestling in the first place.

“One day at the gym, I found out about the Ukrainian Wrestling Arena by total accident,” he says. “A friend asked, ‘Wanna be a referee at one of the matches? Good story — an American refereeing!’ I said, ‘Hell no! I’m not some referee — I’m a fighter!’”

Dustin’s been in the game for two decades. He’s held titles in US promotions like FTW and CZW, fought WWE talent, and specializes in hardcore matches.

“That’s how I got into Ukrainian wrestling,” he says. “We’re growing — first it was 350 people, then 440. Our last show? A record-breaking 500. Our guys are young, a lot of them just debuted, but they’re eager to learn. They watch WWE and AEW — and I show them indie wrestling too, like the Japanese scene. Unfortunately, the world doesn’t know Ukrainian wrestlers. But this is a chance to build unique stars. UWA is a real talent factory.”

Still, the wrestling world has already seen a Ukrainian — they just didn’t realize it.

Imperialism in wrestling?

In 2006, Ukrainian Oleg Prudius signed a contract with WWE. For several years, he competed in the world’s top promotion. In 2011, he even won the Tag Team Championship and once defeated wrestling icon The Undertaker. But he did all this under the persona of Vladimir Kozlov — a brooding Russian fighter.

Promoting the “evil Russian” is a time-honored WWE tradition. In the mid-2010s, they spun a whole storyline around wrestler Alexander Rusev — he’d roll into matches on a T-55 tank, wave the Russian flag, and even beat up an American soldier trying to protect the Stars and Stripes.

Eventually, it was WWE’s golden boy, John Cena, who ended the “evil Russian’s” reign of terror at WrestleMania. Although “Russian,” Rusev was actually Bulgarian — and sports a giant tattoo of his home country.

For centuries, Russia has worked to convince the world that nearly all East Slavic nations are essentially Russian — by force, or by calling them “brotherly” peoples (and often both), followed by erasing their authentic cultures. Those echoes even reach American wrestling, where the “big bad Russian” trope feels familiar and easy to digest.

But after more than three years of full-scale war, that may be changing. Today, the Ukrainian soldier is a globally recognized figure.

Fighting between battles

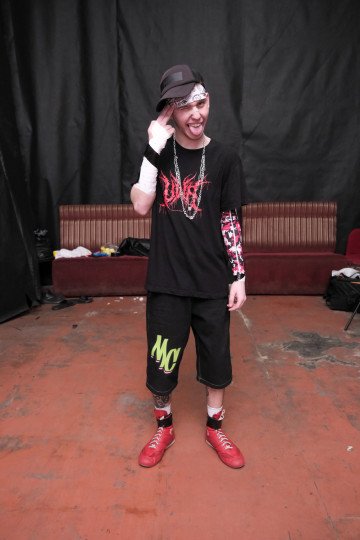

Ukraine’s wrestling roster features dozens of fighters with wildly different gimmicks —from MC Kosher, a rapper, and Viktor Vitrolom , a punk with a long green mohawk, to religious fanatic Alex Di Sin and hulking Papa Joe in plaid pants and suspenders.

But several characters take the ring in military garb. One of them is Toni, an active-duty soldier in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Organizers say he only appears in shows that fit his service schedule. His Instagram features combat positions and ring footage side by side.

Another is Ranger Leonid, also with Ukraine’s Armed Forces. A comrade from the 14th Brigade gave him his gimmick.

Ranger enters the match with several other wrestlers. The show morphs into a tightly choreographed blend of jumps, power slams, and wild strikes.

Dustin Lee takes a few hits from the same spiked nunchucks he crafted earlier. He returns fire with his equally spiked legs. At one point, the crowd is asked to pass up chairs, which are then smashed over heads. Several tables don’t survive the evening.

The adrenaline is sky-high, amplified by cheap beer. Five hundred people in the old factory chant: “Holy shit,” “This is awesome,” or the Ukrainian “Tse pizdets” — loosely: “Pretty f—ing cool.”

If you’re already becoming a fan: Miller defeated Vedmid; the team “Disgust,” featuring Liubomyr and Levin, failed to reclaim their championship belts from GM Kostiantyn Knyaz and Papa Joe; and Ranger Leonid won a five-man match to earn a shot at the Extreme Championship.

It’s intermission.

Not just entertainment

During the break, Ranger returns to the ring. He shares that a friendly unit’s position was recently destroyed by Russian shelling, and they’re raising funds for new gear — and for drones. An auction follows, selling off Ranger’s memorabilia, spent RPG tubes, a poster signed by the wrestlers, and a weightlifting belt they trained with.

A woman buys the belt for $150 — and immediately gives it to a teenager in a giant panda hat. He proudly slings it over his shoulder and holds onto it for the rest of the night. Later, they tell me the “Panda” is a diehard fan who never misses a show. His brother has only been to four — but is thrilled to hear I’m from UNITED24 Media, which he follows on Instagram. He can’t believe wrestling will be featured there.

A show poster T-shirt fetches nearly $200 — similar merch goes for about $20 at the door. The auction host jokes about how active the bidding is, despite no one even asking about the shirt’s size. One bidder yells from the crowd: “Size doesn’t matter — just bomb the orcs !”

These intermission auctions are a regular feature at UWA events. In the past year, they’ve raised around $10,000 for the Ukrainian military.

UWA is also about openness, simplicity, and closeness to the fans. The main organizer doesn’t hesitate to sweep up shards and debris around the ring during the break. Some attendees drift to the bar, where Dustin Lee—still in shorts and arm guards—gets swarmed with congratulations and questions. One young woman, looking at the bruises and scratches on his back, gasps: “They’re real.”

Well, it’s official: wrestling is a staged show, where everything is real.

“Ukrainians are just like us”

After the break, the matches resume. Toni from the Ukrainian Armed Forces teams up with crowd favorite Gambit for a win. In the final bout, veteran Pepsi Kolya falls to UWA World Champion Kenny Rivera.

As the crowd begins to thin, hardcore fans linger, running from wrestler to wrestler for photos. I ask several fighters how the show felt from their side. They all say the same thing — even if there were flaws, the audience didn’t notice. That means it went well.

A dozen audience members climb into the ring for dramatic photos with the organizers’ blessing. A few wrestlers join them, performing impromptu stunts—slams, jumps, and chair shots—and the crowd can’t believe their luck.

Eventually, the wrestlers hop down and start tearing down the set and folding the surviving chairs.

The next show is already on the calendar. Once held about once a month, UWA now stages them every two weeks. Ukrainian wrestling is growing.

Before leaving, I ask Dustin what he thinks about life — and even wrestling shows — continuing in Ukraine despite the Russian invasion.

“That’s what struck me most,” he says. “In the US, all you see on the news is destruction, shelling, trenches. But here I saw people living. Ukrainians are just like us. They want the same things, listen to the same music — a lot of them speak English. If Americans knew that, if they saw how wonderful these people and this country are, they’d support Ukraine more. In the US, if it snows and the plows are late, school gets canceled. Here, missiles explode in the city—and an hour later, kids are walking to class, the café is open, and everyone carries on. Isn’t that incredible?”

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)