- Category

- Life in Ukraine

How Ukrainians Pass Russian Checkpoint, Through Fear and Uncertainty, to Escape Occupation

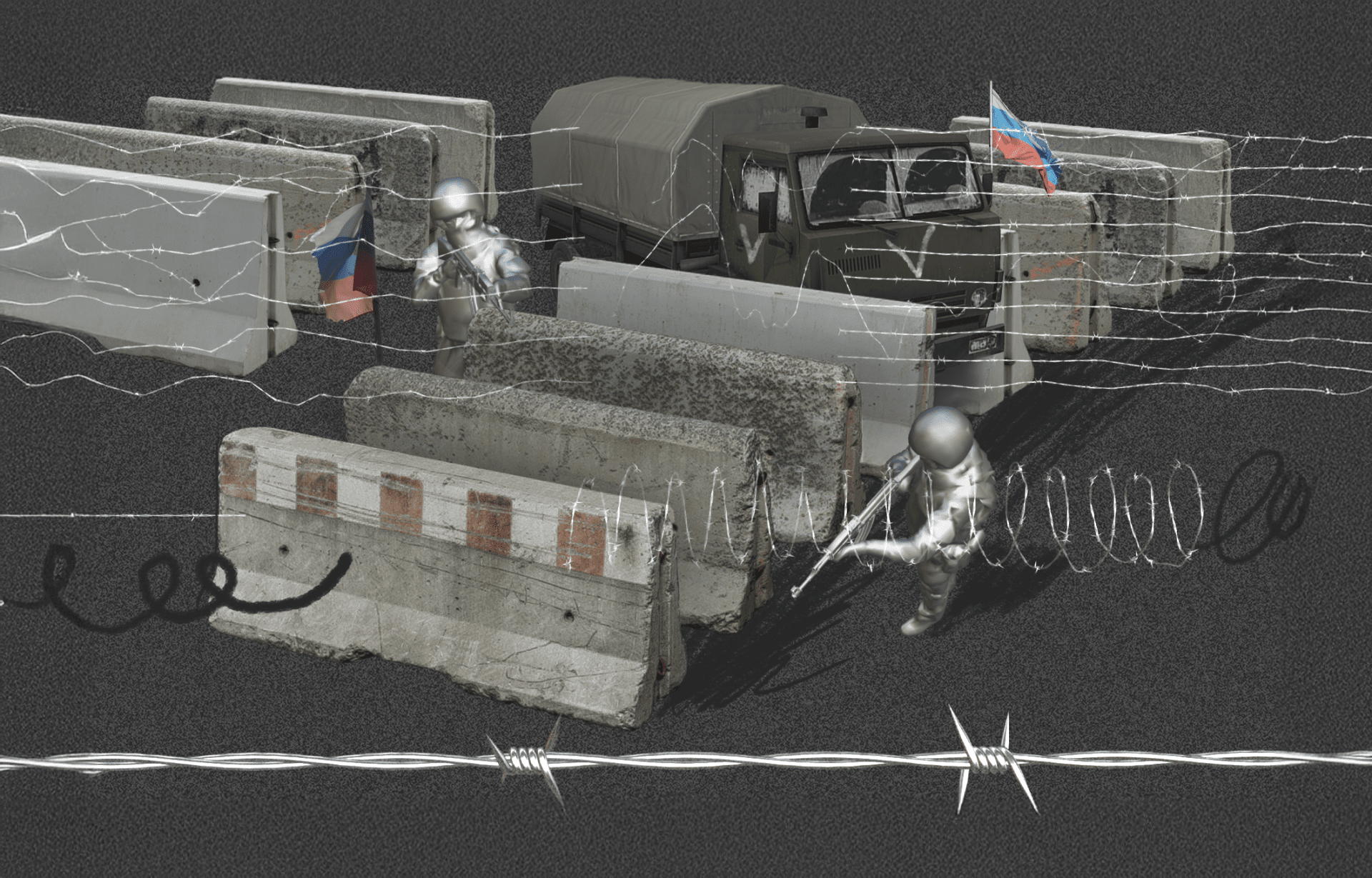

Thousands of Ukrainians trapped in Russian-occupied regions risk their lives on dangerous journeys through heavily guarded Russian checkpoints, trying to reach safety and return to Ukraine. This is the reality of escaping Russian control, torture, and constant surveillance.

Yelyzaveta, 28, never imagined she would leave her hometown. She convinced herself the occupation was temporary. She decided to wait it out, believing Ukrainian flags would soon fly over her streets again.

However, weeks passed, and the situation did not improve. Finally, at the end of April, after two months of occupation, Yelyzaveta decided to leave. As of January 2025, her city of Melitopol, near Zaporizhzhia, remains under Russian control.

The decision wasn’t entirely hers. Her colleagues urged her to leave, subtly at first, then with greater urgency. “It’s not safe,” they said. “You have to go.” It took weeks for her to accept the reality that the war might not end soon.

Doubts weighed heavily on her mind. Could she leave her family behind? What if she didn’t make it through checkpoints? People whispered about cars waiting for days, families turned back, and the terrifying “filtration” process. Some never made it out at all.

It was only after she reached safety that she realized the full extent of the danger she faced. Her name was on a list of people the occupiers considered a threat due to her pro-Ukrainian stance and volunteer work.

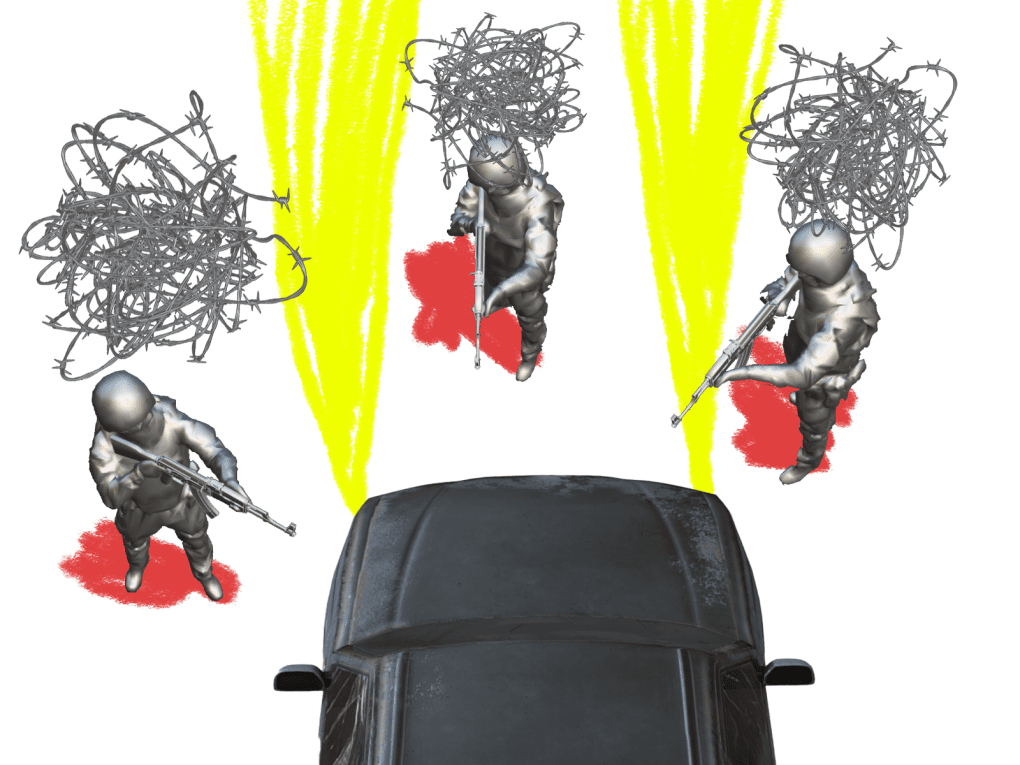

Yelyzaveta’s experience echoes that of thousands trapped in occupied territories, where every decision is uncertain. Some stay, held back by families, pets, or fear of the unknown. Others dare to leave, enduring unpredictable journeys through Russian-controlled checkpoints. Not all of them succeed.

“I decided to leave, but I didn't know if I would make it,” Yelyzaveta recalls. “ At every checkpoint you’re met by a Russian with a machine gun.”

“But staying under occupation… it’s like living in a prison. Russians can break into your house at any moment. Soldiers patrol the streets, ready to stop or search you. We avoided back streets and usual routes to avoid running into them.”

Journey through 28 checkpoints

The route to Ukrainian-controlled areas for Yelyzaveta was nothing like the one-hour drive that once connected Melitopol to Zaporizhzhia. Instead, it was a winding path through rural villages, avoiding main roads and passing dozens of checkpoints.

“There were 28 checkpoints in total,” Yelyzaveta recalls. “Most of them were Russian, and every time they asked questions, searched our things, or checked our phones.”

Preparing for the journey required more than just packing a bag. Yelyzaveta carefully erased things that could raise suspicion—Telegram chats, social media likes, photos.

"I had known of cases where they restored backups on phones and viewed it right away. So when I was preparing, I did it extensively. I completely cleaned my phone. I even removed likes from TikTok videos,” she explains.

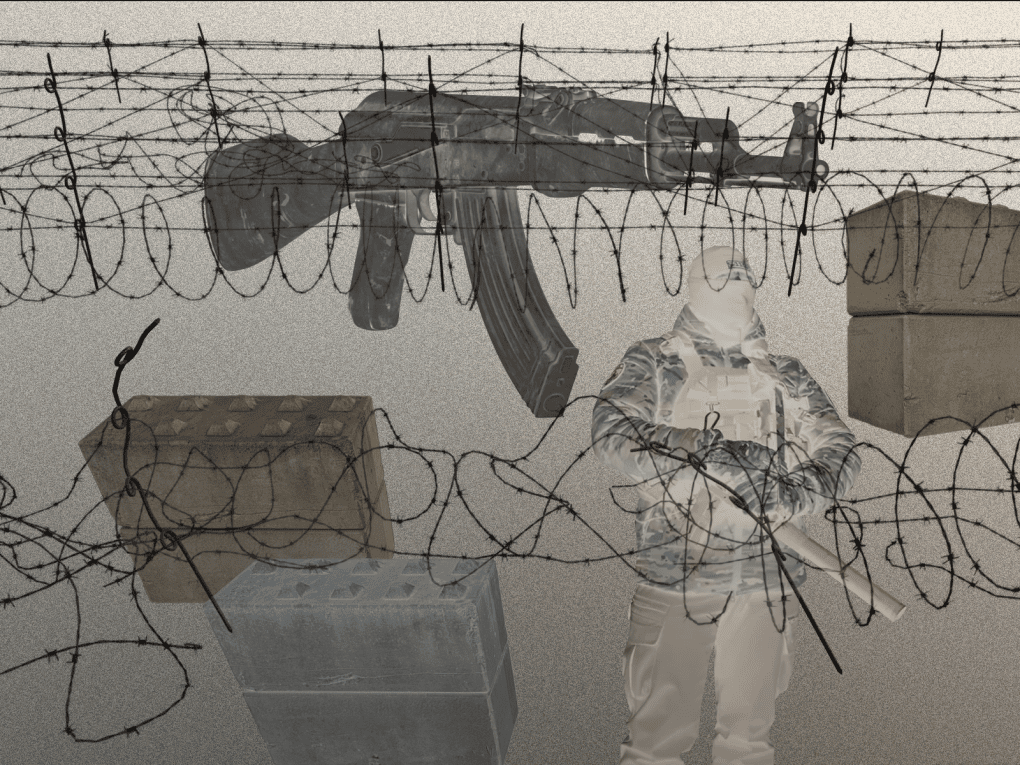

The most rigorous checkpoint was in Tokmak. As their bus approached, soldiers began pulling the men out, inspecting their bodies for tattoos that could link them to Ukrainian forces. Phones were searched meticulously, apps and photos scrolled through as passengers sat in tense silence.

Yelyzaveta was questioned, and when a soldier asked if she had tattoos, she denied it. “My heart was racing,” she says. “If they had decided to check, it could have gone very differently because I have one.”

Packing for the journey was another emotional challenge. “You’re stuffing your entire life into a small suitcase,” she says. Her bag held only the essentials, but she managed to hide a small trident her parents had given her, slipping it into a hidden pocket in her jeans—a reminder of where she belonged.

After more than 12 hours on the road, Yelyzaveta finally reached Zaporizhzhia, the first Ukrainian-controlled city on her route. The relief of arrival was overwhelming, but so was the realization of what she had left behind.

“You’re packing your life into a small suitcase. Only essentials. No books. But I have such a beautiful library at home,” she says.

The journey through Russian checkpoints has become a painful experience for thousands of Ukrainians fleeing occupation.

Those checkpoints are designed to control movement, intimidate civilians, and eliminate perceived threats. Soldiers search for signs of loyalty to Ukraine, including tattoos, phone data, and social media activity.

The process is often arbitrary. Men are more likely to face physical searches, while women are subjected to psychological pressure and questioning. Vehicles can be held for hours or days, and some people are turned back or detained indefinitely.

As of 2025, the only way out of occupied territories is through Russia. Once there, individuals can attempt to travel to third countries or return to Ukraine. Leaving requires money, resilience, and a willingness to endure the filtration process, which includes detailed interrogations, background checks, and invasive searches.

Previously, Kolotylivka-Pokrovka crossing on the Russian-Ukrainian border near Sumy was the only possible way, offering a direct route into Ukrainian-controlled areas. However, it closed in August 2024, cutting off this vital connection. Today, all routes from occupation lead through Russia, a journey full of danger and stress.

From Russia to Europe

For Anton, 25, leaving occupied Kherson was a decision out of desperation. After almost 10 months of occupation, the turning point came when a mortar shell hit a house just meters from his own.

"That was it," he told me. "We couldn’t stay any longer.” Along with his mother, Anton decided to escape to Russia—first step toward reaching safety in Europe.

Their journey began with a bus ride to Crimea, passing through multiple Russian-controlled checkpoints.

"At one of the checkpoints, I was pulled aside for what they called filtration," Anton explains. "They separated me from my mother, leading me to a row of metal containers under camouflage netting. It was freezing," he says, describing the 3 hours wait in the winter before he was called inside.

Inside the container, a young Russian soldier interrogated him. Questions ranged from his past employment to his views on the war, each word weighed carefully to avoid suspicion. “You have to play along with their propaganda,” Anton admits. “You tell them what they want to hear, even if it’s against everything you believe.”

Unlike women, who often passed through with fewer checks, men were required to undergo detailed inspections. "You’re cold, tired, and constantly thinking about what to say so they don’t twist your words against you."

According to a 2022 The Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) research, Russia’s filtration system involves several levels of control. The first level occurs at checkpoints, where individuals are checked and tagged if considered suspicious. Those who fail to pass are sent to filtration camps, where conditions worsen.

The third and more brutal level of filtration takes place in prisons and pretrial detention centers. Individuals suspected of disloyalty to Russians are held indefinitely, tortured or executed.

Despite the Kremlin’s public claims that these processes are “evacuations,” the study confirms that the camps are designed for the systematic repression of Ukrainians, where Russians either try to assimilate or destroy them.

Anton was “lucky” to be released after the first level of filtration, but the road ahead was no less grueling. He and his mother spent 5 days traveling through rural roads to avoid major highways and additional scrutiny. The bus was overcrowded, with limited stops for food or rest.

“There wasn’t much money for food, so we barely ate,” Anton says. “I had borrowed $1,000 from my sister, and almost all of it went to the driver for the journey.”

Their last Russian checkpoint was in the village of Krasnaya Gorka, near the Belarusian border. Here, they were required to sign statements declaring they had no grievances against the Russian Federation and were traveling only in transit. “Once we entered Belarus, the pressure eased,” Anton recalls.

The journey ended in Lithuania, where Anton, his mother, and his fiancée—who had fled the occupation earlier—now live temporarily. “All of us plan to return to Ukraine, whether in the best or worst-case scenario,” Anton says.

Why do these checkpoints still exist?

When Russia occupies Ukrainian cities and declares them part of its territory, one might assume that checkpoints would be removed. Yet, these checkpoints remain firmly in place, and their purpose goes far beyond simple security.

A 2023 study by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) explains why Russia needs these checkpoints. The Kremlin uses them to prevent men from occupied Ukraine from escaping forced mobilization, stop Russian conscripts from fleeing back to Russia, and maintain filtration measures to suppress and control the local population.

This paradox highlights a deeper truth about the Russian's governance in occupied territories. “The existence of these checkpoints further highlights that Russian officials do not view the residents of occupied Ukraine as Russian nationals and are governing as the occupying power they are, despite the ongoing claims the illegally annexed territories are part of Russia," according to the research.

For Anton, the brutality of this system is deeply personal. “The whole situation was pure stress,” he recalls, describing the experience of passing a chackpoint. “You’d stand for three hours in the cold, and then they’d pull you into a warm room and start asking those strange, impossible questions you couldn’t answer directly.”

Anton’s story is a stark reminder of what it means to live under occupation: a daily struggle for survival, where even a simple act of speaking carries risks.

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)