- Category

- War in Ukraine

How a Country Without a Navy Defeated the Largest Black Sea Fleet and Restored Its Exports

February 2024 was a record month for Ukrainian maritime exports since the start of the full-scale invasion: about 8 million tons of cargo were shipped through its ports. But how did that happen? We look at the Ukrainian Sea Corridor and how it came into existence.

Ukraine, as one of the world's top 5 grain exporters, holds approximately 10% of the global market. A lot of this grain goes to the Middle East and Africa, often through UN food security programs. Sea transport, specifically via the Black Sea in southern Ukraine, is the primary and most cost-effective export method.

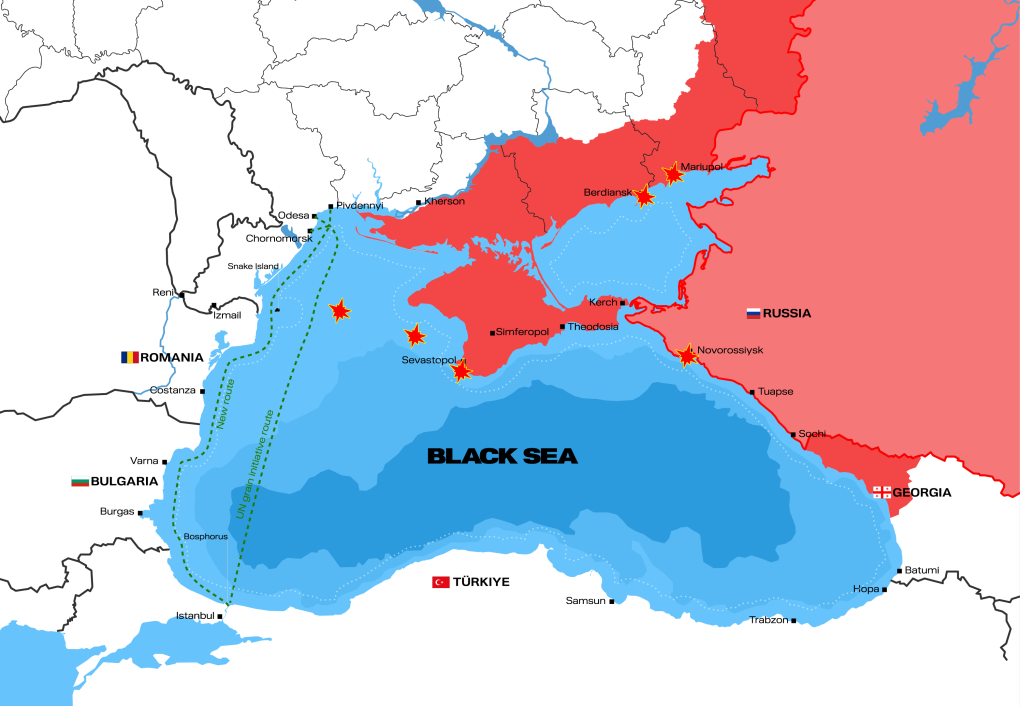

The full-scale war in Ukraine, which began in February 2022, halted this crucial export route. Over a dozen ports ceased operations, and Russia's Black Sea Fleet effectively blockaded the region, preventing even civilian cargo passage. Decades-old logistics systems ground to a standstill.

Grain and agricultural products suddenly lacked a way to reach markets. Railways, trucks, and the assistance of neighboring countries stepped in to facilitate exports. However, this led to new challenges like infrastructure limitations, transport shortages, and rising costs.

Ukrainian exporters had to adapt to survive, seeking income and needing to clear old harvests to make space for new ones. The situation presented a major economic blow for Ukraine, as agricultural products are its top export. In 2021, these exports generated $27.7 billion in revenue, comprising a third of the nation's total exports.

The "grain corridor" was a lifeline for Ukraine. At the initiative of Ukraine, the UN, and Turkey, Russia agreed not to attack civilian cargo ships carrying agricultural products. This agreement allowed Ukraine to resume exports of grain and other agricultural products, which are essential to the country's economy.

Sadly, this lifeline wasn’t enough for Ukraine's needs. Ukraine exported roughly 44 million tons of grain annually before the war, but the agreement limited monthly exports to a mere 1-2 million tons. Russia intentionally sabotaged the process, knowing it would deplete Ukraine's resources. In July 2023, Russia withdrew from the agreement entirely, effectively banning safe exports.

The problem extends beyond grain. The blockade also crippled the export of metals, minerals, and chemicals – roughly half of Ukraine's pre-war export economy.

Ukraine desperately needed full sea access for cost-effective exports, free from Russian interference. In the summer of 2023, after much effort, this was achieved.

Successful military operations at sea, combined with international cooperation, pushed the Russian fleets back. The results are undeniable:

February 2024 set a record for Ukrainian sea exports since the invasion: approximately 8 million tons of cargo shipped. Compare this to the "grain corridor," which moved only 17 million tons of agricultural products in nearly six months.

Ukrainian officials are optimistic this trend will continue. If so, Ukraine may approach 100 million tons of sea exports in 2024. While still below pre-war levels (159 million tons in 2020, 153 million tons in 2021), this would be a remarkable achievement given the ongoing war.

Part 1: Driving the Russian Black Sea Fleet away from the ports of Greater Odesa and the Danube

Ukraine's primary challenge in restoring Black Sea exports was Russia's control of the Black Sea. Lacking a strong navy of its own, Ukraine had to find innovative ways to protect its coastline and counter the enemy.

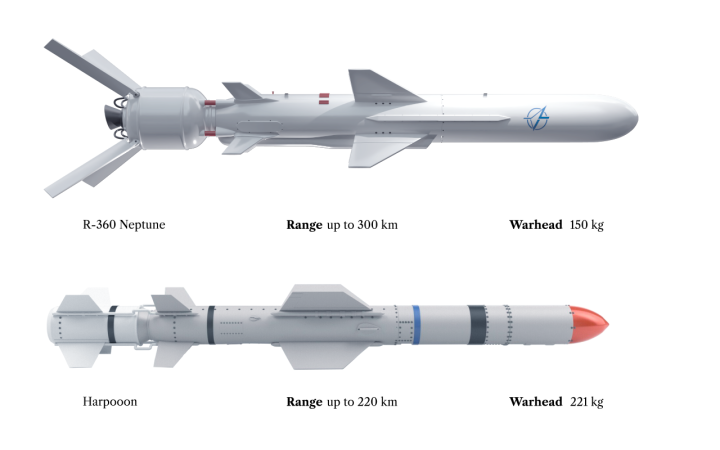

Neptunes and Harpoons

Ukraine had developed its own "Neptune" anti-ship missiles, first used in 2022 to sink the Russian cruiser "Moskva," a $750 million flagship of the Black Sea Fleet. This significantly weakened Russia's naval dominance.

In the spring of 2022, Ukraine received Harpoon anti-ship missiles and launch systems from Denmark, the UK, and the Netherlands. This aid, combined with Ukraine's missiles, made a large stretch of coastline safer, primarily protecting against potential Russian landings. Today, this safer zone allows civilian cargo ships passage.

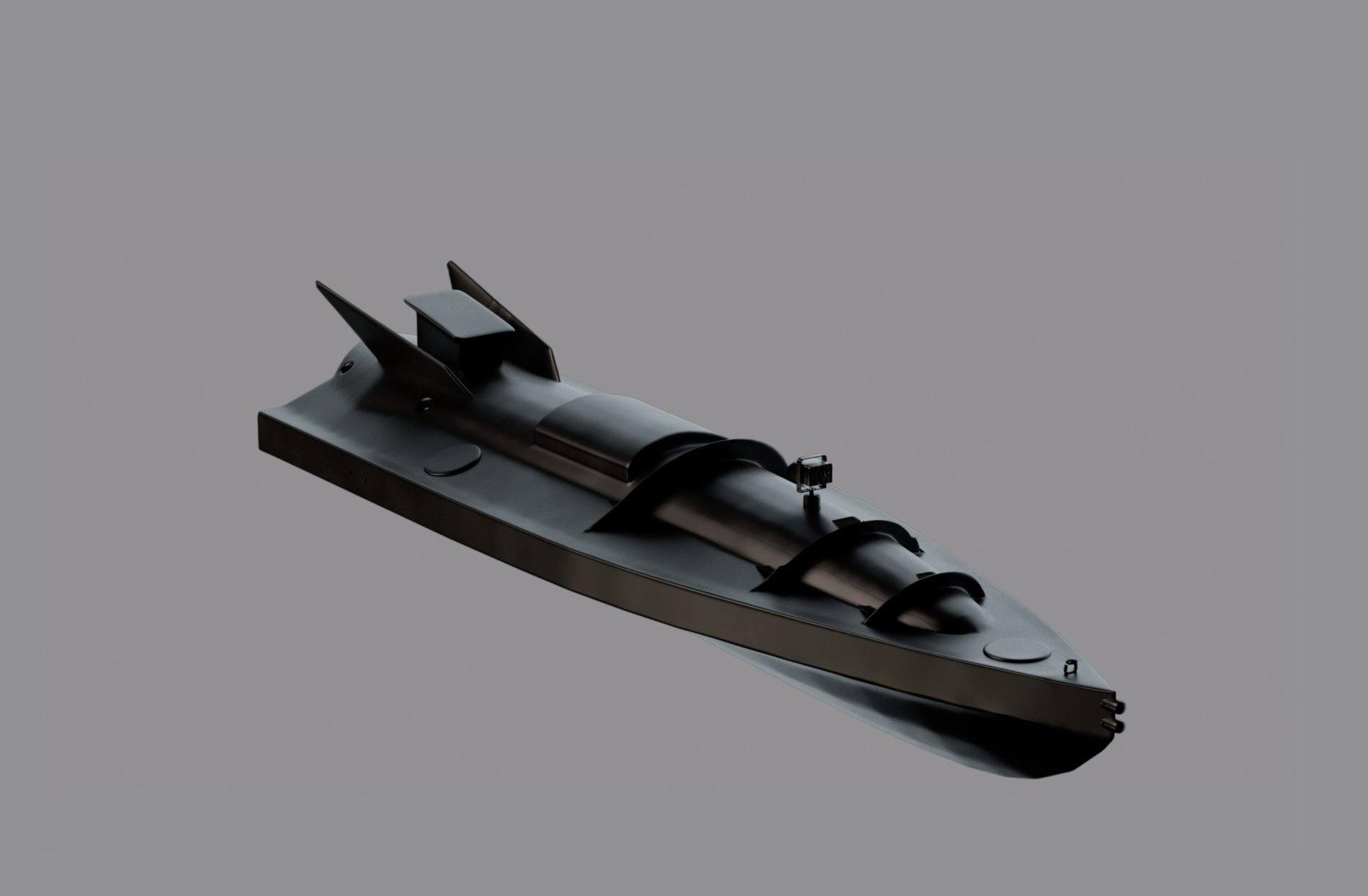

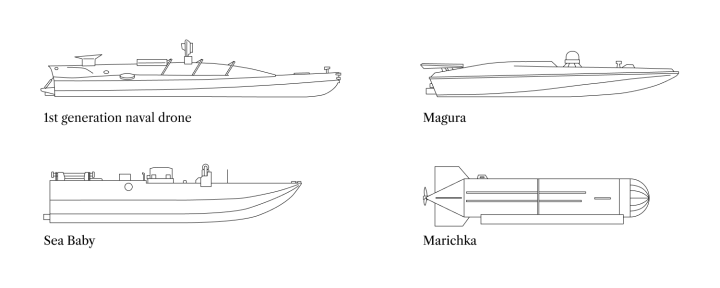

Ukrainian naval drones

The development of naval drones was another turning point for Ukraine. In October 2022, naval drones were first used to attack Russian ships in Sevastopol, damaging the frigate "Admiral Makarov" and the minesweeper "Ivan Golubets."

Unable to quickly build, buy, or receive a traditional fleet during the war, Ukraine focused on rapidly developing and producing naval drones to fight Russia.

This strategy proved successful. Over the next year and a half, Ukraine carried out numerous drone attacks on the Russian fleet. Fearing the drones, Russian ships largely retreated to Crimean bays. In total, Russia lost or sustained damage to over two dozen warships, severely crippling their landing capabilities.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet proved vulnerable to these small, maneuverable, and relatively inexpensive naval drones. Long-range missiles from Ukraine's allies further weakened the fleet.

Allied assistance

Allied support was crucial, particularly the transfer of long-range Storm Shadow missiles and their French counterpart, SCALP. These weapons allowed the Ukrainian Air Force to attack the Russian fleet even when docked in harbors. Ukraine even managed to damage a submarine worth over $350 million. Consequently, Russia was forced to withdraw part of its fleet from occupied Crimea to the Russian port of Novorossiysk.

Allied weapons enable Ukraine to target the Black Sea Fleet's bases with airstrikes. Importantly, Ukraine uses Storm Shadow and SCALP missiles exclusively against military targets in temporarily occupied Crimea, not on Russian territory. These missiles are used strategically due to Ukraine's limited supply. Each operation is carefully planned and highly successful in destroying targets, including Black Sea Fleet bases, communications centers, air defense systems, and landing ships.

Part 2: Developing the infrastructure of Danube ports and new routes

Ukraine couldn't afford to halt exports after Russia withdrew from the grain deal in July 2023. Grain exports are vital for two reasons: they support Ukraine's largest export industry (employing over 3 million in agriculture pre-war) and generate essential foreign currency. While Ukraine is grateful for its partners' aid, it must independently cover its military expenses. Moreover, Ukrainian ports handle 70% of the nation's imports and exports.

Launching its own sea corridor became a necessity. Ukraine implemented two successful strategies:

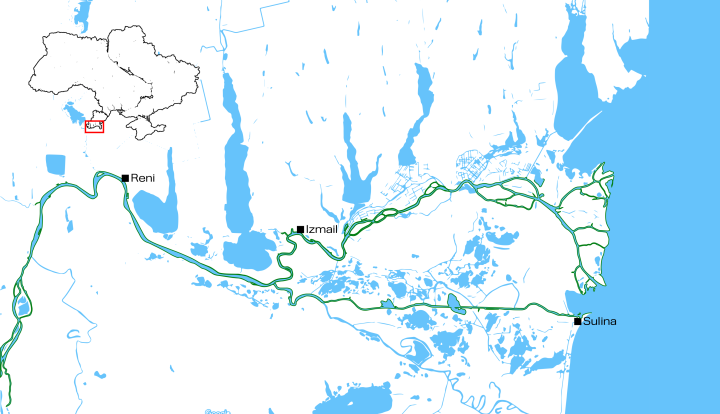

Danube ports

Ukraine increased its reliance on Danube ports after the full-scale invasion. Though geographically further south with more complex logistics, their proximity to Romania (a NATO member) was a lifesaver. Larger ports in Odesa and Kherson were inaccessible or threatened.

This strategy worked. In 2022, Danube ports accounted for 12% of exports, rising to 29.2% a year later. In 2023, heavy investment by private Ukrainian agribusiness funded 23 new Danube cluster terminals. To accommodate larger ships, channels were deepened, more pilots were hired, and operations went 24/7 where possible. The Danube temporarily became Ukraine's primary export route.

Return of the ports of Greater Odesa

After the "grain corridor" ceased, Ukraine established its own independent sea corridor. Routes ran through Ukrainian coastal waters and 12-mile zones belonging to Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey. To reassure shipowners, Ukraine formed an insurance fund with leading British insurers.

This proved successful! In autumn 2023, Ukraine exported 8.6 million tons of cargo. While less than the grain corridor, importantly, 2 million tons were non-agricultural. This reopened exports vital to Ukraine's metallurgical industry, which relies on cost-effective sea transport.

The corridor's success is clear. In February 2024, over 8 million tons passed through, with further growth potential. This compares favorably against only 1.4 million tons in September 2023 when the corridor first launched.

Why is this important?

The Ukrainian sea corridor is a perfect example of how Ukrainian partnership with Western partners can work. The transferred weapons helped to drive Russian ships away from Ukrainian coastal waters, and long-range missiles - to try to return. And working with the Romanian government allowed us to quickly increase exports from the ports of the Danube cluster and at one point prevent exports from stopping.

The increase in exports made it possible to regain the ability to receive foreign exchange earnings and not leave millions of people without work, and tens of millions - without access to food: a significant part of Ukrainian grain was exported to African countries and the Middle East.

Ultimately, this maritime strategy worked. By restoring maritime exports of goods, Ukraine has significantly reduced the pressure on its land border partners. Now no more than 300 thousand tons of grain are exported from Ukraine by rail and road transport every month. Therefore, this will allow to relieve pressure on the infrastructure of partners.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)