- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Ukraine’s Black Sea Strategy Keeps Russia's Fleet At Bay

Ukraine has been pounding Russia’s Black Sea Fleet since the full-scale invasion started, in a bid to repel the threats of missile attacks from ships deployed around its southern coast. Russia’s Black Sea has been forced to relocate most of its ships, but can it work its way back to Crimea?

The sinking of Russia’s $300 million worth ‘Rostov-on-Don’ submarine in Sevastopol on August 2nd was the latest chapter in a series of blows that turned the tides in favor of Kyiv in the Black Sea.

Ukraine’s military was quick to revel in its success after sinking the submarine, one of four Russian Kilo-class submarines capable of launching Kalibr missiles regularly fired over Ukraine.

"The destruction of 'Rostov-on-Don' once again proves that there is no safe place for the Russian fleet in the Ukrainian territorial waters of the Black Sea," the General Staff wrote on August 3rd.

The Destruction of Russia’s ‘Rostov-On-Don’ Submarine: A Turning Point

Such relentless pounding explains why Russia reportedly decided to relocate most of its fleet further away from Sevastopol and Crimea, where waters are proving treacherous for its warships.

The ‘Rostov-on-Don’ was the latest addition to an embarrassingly long list of Russian shipwrecks rusting in the Black Sea’s depths.

Against all odds, Ukraine brought the war to the Black Sea thanks to an innovative combination of missiles and naval drones.

It made up for its lack of navy in a series of successful strikes, leading to humiliating losses for Russia.

Such a hit is no small feat for a country without a real navy to its name compared to the Black Sea Fleet.

The strategy proved fruitful, as Russia slowly decided to relocate the remnants of its fleet to safer harbors, virtually keeping the flotilla at bay.

“The Russian Black Sea Fleet has suffered significant losses,” military expert Andrii Kharuk told United24 Media.

“It is unable to control maritime traffic and protect its main base in Sevastopol,” he said.

What’s Left Of the Black Sea Fleet?

Over 30 Russian ships were reportedly still active in the area, according to Ukrainian Navy spokesman Dmytro Pletenchuk. Russia lost almost 30 vessels, a third of a fleet that boasted 74 warships before the full-scale invasion, Pletenchuk told Newsweek.

Saratov amphibious landing ship (March 2022): The strikes started in March 2022, when the Saratov, a large Alligator-class amphibious landing ship able to carry about 400 troops, as well as 20 main battle tanks or 45 armored vehicles, was destroyed by a Ukrainian Tochka-U missile while docked in Russian-occupied Berdiansk.

Moskva flagship (April 2022): The Moskva, the Black Sea Fleet’s flagship, was struck in April 2022 by a long-range Neptune missile. It was the first time Russia lost a flagship since the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.

Admiral Makarov frigate and minesweeper Ivan Golubets (Fall 2022): Ukraine started using unmanned naval drones in the fall of 2022 to damage the frigate Admiral Makarov and the minesweeper Ivan Golubets.

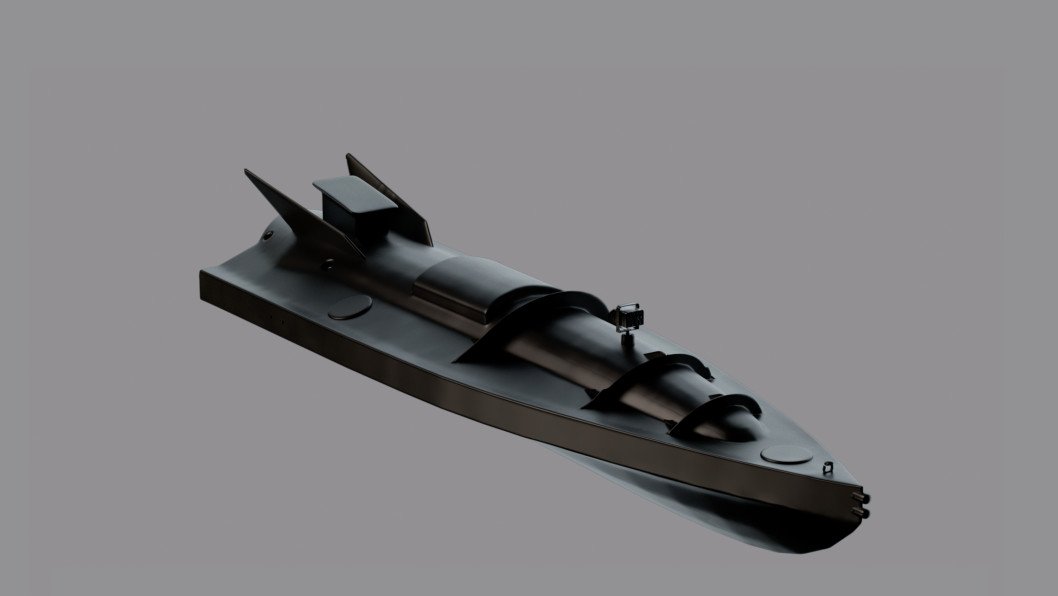

The Ukrainian Navy has since started to develop its very own naval fleet of drones, including the Magura V5, able to carry a 300-kilogram warhead, and the Sea Baby, able to carry about 800-kilogram of explosive - roughly twice the payload of a US Tomahawk missile.

How Ukraine’s Drone And Missiles Strategy Forced the Black Sea’s Retreat

Thanks to its harassment “mosquito” tactic, Kyiv skillfully managed to challenge Russia’s Black Sea Fleet’s control over the body of water and forced the Russian Navy to relocate most of its ships from occupied Crimea to Novorossiysk, in Russia's Krasnodar region, or further, in Russian-occupied Abkhazia.

“Now ships and boats of the Black Sea fleet of the Russian Federation do not actually sail in the direction of the territorial sea of Ukraine,” Ukraine’s former Southern Defense Forces' spokesperson said in October.

And the Russian Navy might be stuck in the Black Sea.

According to Alper Coskun, a researcher at the Geopolitical Intelligence Services, Russia’s losses in the Black Sea are “next to impossible” to replace.

Russia can’t deploy new ships in the area, at least not through the Dardanelles and the Bosporus straits, controlled by Turkey.

Turkey closed its straits to transit of military vessels that are not based in the Black Sea since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, invoking Article 19 of the Montreux Convention.

Turkey forbids any other vessel from coming in, stopping Russia from replenishing its fleet and transforming the body of water into a deadly trap if Ukraine manages to get longer-range missile capacity.

Thus, Russia has to bring smaller missile ships through rivers, like the Volga River to the Don-Volga Canal, then the Don River and the Azov Sea, according to Defense Express.

However, experts have noticed an opposite trend recently, and smaller boats seem to be relegated to other fleets rather than the Black Sea one, Kharuk said.

Russia’s Missiles Threat From the Black Sea

And yet, Russia’s Black Sea fleet’s apparent retreat doesn’t mean it’s less dangerous. The dwindling flotilla hasn’t lost its ability to launch Kalibr missiles over Ukraine, Kharuk added.

“The only threat is the use of ships as platforms for cruise missiles,” Kharuk said.

The Black Sea Fleet still has several submarines, frigates, corvettes, and various small ships and boats able to launch 2,500-kilometer-range Kalibr missiles towards Ukraine.

The fleet could reportedly launch a salvo of 70 Kalibr at once in 2022, an estimation reduced to 40 in 2024, according to a Marshall European Center for Security Studies research.

According to Kharuk, most of Russia’s Kalibr missile-capable vessels remain undamaged.

Those include three submarines, two frigates, and four such corvettes that still operate in the Black Sea, but Ukraine’s harassment tactic limits their activities, he said.

Why Russia’s Black Sea Fleet Cannot Recover: Sanctions, Shipbuilding Challenges and Ukrainian Advances

Shipbuilding deliveries have reportedly increased over in 2023, with the commission of three submarines, three frigates, and smaller corvettes, according to a report by Dr Michael B. Petersen, founding director of the Russia Maritime Studies Institute, for the Chatham House think tank.

However, competition between different army corps over the budget and years of losses for United Shipbuilding Company (USC), the state-owned umbrella enterprise for naval construction, may hamper the construction of new warships.

Sanctions also play their roles since Russia’s shipbuilding industry lost most access to Western technologies and has had to turn to China, whose diesel engines, for instance, have proven unreliable.

Russia also faces a shortage of trained shipyard manpower as Russian dictator Vladimir Putin keeps mobilizing new troops.

On top of that, Crimean shipyards are no longer safe for building new vessels.

It’s risky for Russia to keep its unfinished boats in the occupied peninsula, as the example of the ‘Askold’ corvette shows.

In November 2023, Ukrainian forces hit the Zaliv shipyard in occupied Crimea, damaging the Karakurt-class corvette ‘Askold’ while it was still on dry docks. The ‘Askold’ was reportedly hit by Franco-British Storm Shadow/ SCALP long-range missiles.

“These (missiles) have the greatest potential,” Kharuk said.

If the US added the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile to Ukraine’s recently acquired F-16, these would prove deadly effective.

The JASSM can carry a 450-kilogram warhead, with a range of 1,000 kilometers, which could unleash the potential of F-16s' lethal radius and create a serious threat to Russia’s Black Fleet.

Yet, these missiles are still on Ukraine’s wishlist, and it’s unclear how long it will take to get them to defend Ukraine’s skies and Black Sea.

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)