- Category

- War in Ukraine

Ukraine Is Actually Producing a Significant Amount of Its Own Weapons

Missiles, drones, artillery—the Ukrainian defense industry has reinvented itself since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Today, the challenge is to find sufficient funds for orders—to keep it going.

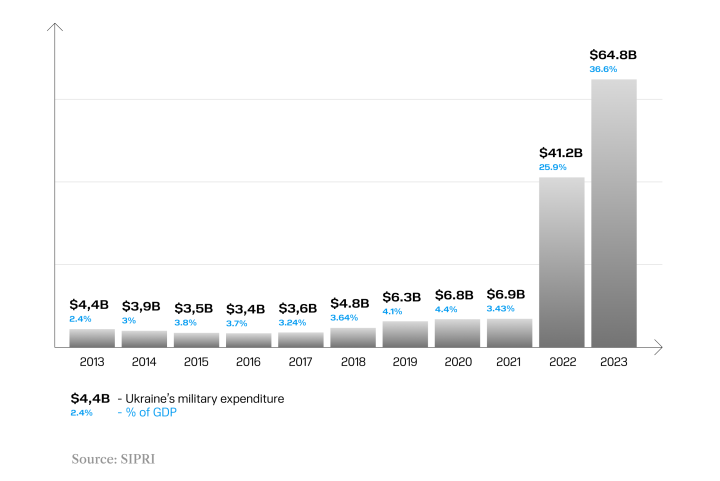

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian state-owned company “Ukroboronprom” was among the top 100 largest arms producers—manufacturing products worth over $1 billion. But this is almost 15 times less than what Russia produced, which has always been one of the world's largest arms exporters.

Russia’s invasion on February 24, 2022, changed everything. Ukraine was supported by its partners: Britain, the US, the EU, Japan and Australia. They gave Ukraine thousands of units of equipment and weapons, hundreds of thousands of artillery shells, and millions of bullets. However, because of the unprecedented intensity of this war, even such assistance was not enough. There was also the significantly greater power of the enemy: Until February 2022, the Russian army was considered a serious contender to NATO forces.

Under such circumstances, the answer is obvious: a country at war must establish its own production of weapons—different and most importantly, effective weapons. To some extent, Ukraine has succeeded in this.

The Ukrainian defense industry has significantly grown in two years of full-scale war. But what holds it back from further growth? And which Ukrainian-made weapons are already working at the front?

A brief overview of the industry

Today, the Ukrainian defense industry employs more than 300,000 people in both state and private enterprises, with the latter's share growing significantly.

Before the full-scale invasion, the state controlled the defense industry almost entirely. Today, it is opening up to private competition. According to the Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, free market conditions are key to the development of this industry. That is why Ukraine has been trying to create them since 2022.

It seems to have worked: about 500 companies now operate on the market. Only a fifth of them are state-owned, all the others are private. At least a third of all companies are tech innovation projects producing modern weapons.

On a global scale, Ukraine still produces relatively few weapons. In 2023, the market volume was about $3 billion. It is, of course, limited by the capabilities of Ukraine—which is the leading buyer of these weapons. The country's leadership promises that in 2024, purchases will grow to $6 billion. The potential is at least three times greater.

What does Ukraine produce?

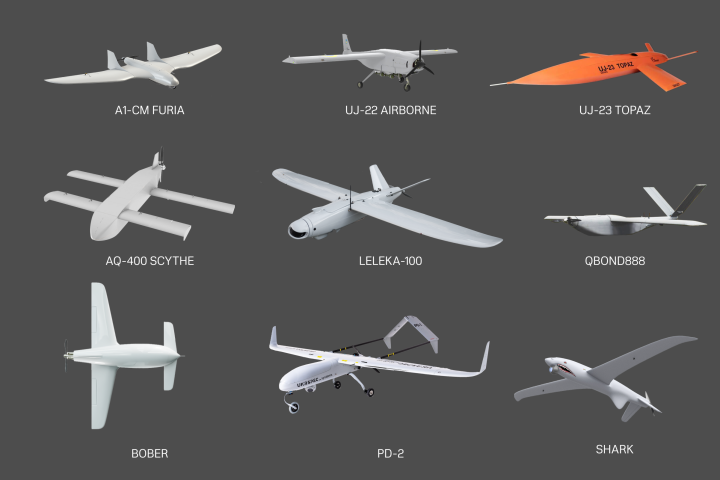

Drones

From the first days of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine began using the equipment it had at hand. Resources were limited, so anything that could help protect the country was put into use.

That’s when they started using drones, which, just some time ago, were used by amateurs to take videos of nature and were even jokingly called "wedding drones." But months of war showed that a $1,000 drone could both conduct reconnaissance and drop homemade shells on Russian positions. Drones became paramount.

That is why Ukraine and many volunteers began to import all possible types of drones from abroad. These included Turkish strike Bayraktar drones, reconnaissance drones, the simplest consumer drones, and even drones intended for the agricultural industry—which were also suitable for reconnaissance.

This demand launched an entire industry: Ukraine took on the task of manufacturing drones itself. According to the Ministry of Digital Transformation, more than 200 manufacturers of various types of drones operate in Ukraine today. Hundreds of small and large companies assemble FPV drones like the "kamikazes."

For this new industry to work at full capacity, dozens of laws had to be changed, restrictions removed, and government purchases organized.

Today, Ukrainian drones are used both on the front line and deep behind enemy lines—at a distance of over 1,000 km.

In the winter of 2024, a closed presentation of new combat products took place in Kyiv. As the Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov said, "Oil depots in Russia are not burning for nothing."

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy clearly outlined the goal: by the end of the year, Ukraine must purchase and manufacture over 1 million drones on its own. The state assures that there are opportunities for this.

Drones are easier to assemble than conventional tanks. They are also relatively cheap, and can inflict significant damage to the enemy—both at the front and far beyond its borders. What's more, you don't need to build a huge factory to produce them—it's enough to gather engineers in a secure room and organize the timely delivery of components. For a country with limited resources, this is a good option.

And they are also super effective.

This has been vividly demonstrated by Ukraine's latest development—sea drones. Two projects called Magura and Sea Baby have destroyed up to a dozen Russian Black Sea Fleet ships.

Small sea drones with a warhead of several hundred kilograms can travel up to 1000 km at a speed of 50-70 km, reach Russian bases undetected, and attack them. The mass nature of operations—when three to seven such drones can attack simultaneously—adds to the difficulty of defending large ships.

Along with the long-range Storm Shadow and SCALP missiles from allies, Ukraine has managed to destroy—or send for repair—almost all aircraft carriers of the Black Sea Fleet, forcing the Russians to move the remnants from Crimean ports to Novorossiysk and significantly reduce the scale of their activities in the Black Sea.

Moreover, the cost of a sea drone is about $200,000, while the ship it attacks can be valued at $60-$70 million. And the main thing is the time of its restoration or construction: it takes years.

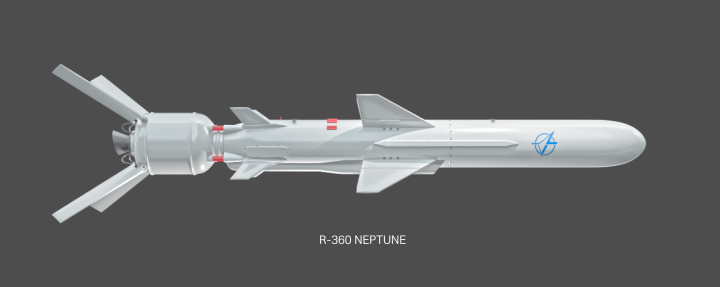

Missiles

Even before the start of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine had its own anti-ship missiles called Neptune. Over the past 10 years, they were developed by the Ukrainian design bureau “Luch” and were produced at Ukrainian enterprises. The missile had a range of up to 280 km and a speed of up to 900 km/h.

The missiles almost immediately proved themselves in battle and destroyed what seemed an unattainable target: the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet, a large cruiser named Moscow, worth $750 million.

The problem was that the stock of these missiles was minimal at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Despite this, they went into production and were even adapted for launch not just from land.

But more was needed.

The allies are supporting Ukraine in the provision of long-range missiles, which allow strikes to be carried out up to 250 km deep into enemy territory. But more is needed, considering that Russia has missiles that can hit much further: 500km+ and more.

That is why Ukraine has taken on the development of its own version of long-range missiles. Oleksandr Kamyshin, Minister of Strategic Industries of Ukraine, says that Ukraine is already working on a rocket that will be able to hit targets at a distance of 700 km. This will allow the destruction of military targets installed by Russia in the illegally occupied Crimea, as well as strikes on military bases in its border regions.

In addition, according to Ukrainian officials, the development of air defense systems is underway.

But all this is an extremely long process that requires resources. Modern weapons are high-tech, so it can take months to assemble a finished product. For example, it takes 40 months to manufacture the already developed Aster missile for the French SAMP/T system. However, development also takes a long time, and different countries often partner with each other to speed up the process. For example, Storm Shadow/SCALP was a joint British-French project. It took 8 years to develop the missile.

Self-propelled artillery units (SAUs) / armored vehicles / ammunition

Russia’s war against Ukraine is a war of artillery—artillery helps both attack and defend. That's why Ukraine needs it so much.

Thankfully, Ukraine has its own artillery development called Bogdana—a self-propelled artillery unit on a wheeled platform capable of firing at a distance of up to 60 km. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine had one of them, and it was often used as an exhibition piece. In 2024, Ukraine can assemble up to 8 units per month. France has the same capacities for its Caesar SAUs.

This still needs to be improved to meet Ukraine's needs for artillery systems, but the increase in artillery capacity is ongoing. Six months ago, Ukraine could assemble six systems a month.

Another problem is ammunition. The production of artillery shells is a problem for both European countries and the USA, as well as for Ukraine. Before the full-scale invasion, nobody had large amounts of them anywhere. The volume that the States were making was about 20,000 units per month. At the most active moments of the full-scale invasion, Russia could fire 60-70,000 shells per day along the entire frontline. The difference is obvious.

As of today, the situation is improving. Ukraine does not give exact figures, but according to Prime Minister Denys Shmygal's statements, in 2023, the production of artillery shells in Ukraine increased by 2.5 times and mortar shells by 42 times. Improvements are also taking place among partners: in the US, production has grown by 2-3 times in two years, and with further funding, it can reach 80,000 shells per month.

The situation with armored vehicles is a little better: dozens of different private companies have taken up the production of armored vehicles of various types and classes. For security reasons, the state does not provide detailed information about this, but according to Kamyshin, local manufacturers are ready to supply almost all types of demanded armored vehicles, and the market itself has increased in volume several times over.

What is slowing down the Ukrainian defense industry?

Ukraine cannot produce the entire range of weapons it needs—such as aircraft, tanks, or high-precision air defense systems. These are complex technological weapons, the development of which alone takes years. But a large amount of what the front needs today can already be provided independently. There is a problem, though, and it’s money.

The state has allocated $6 billion for the purchase of weapons from domestic manufacturers in 2024, which is the maximum amount that Ukraine has. At the same time, the capabilities of Ukrainian enterprises are at least three times greater than the capabilities of the state. Ukraine is already spending all the money it has in the budget on defense—about $40 billion.

But there are ways for Ukraine to scale:

Firstly, through joint defense enterprises. Turkish Baykar has been talking about a joint project in Ukraine for a long time, as well as the German Rainmetall, which seeks to build several joint ventures in Ukraine.

Secondly, through private Ukrainian companies are already producing a competitive product on the world market—drones. The prospects are creating an industry with estimates of hundreds of millions of dollars and contracts worldwide. Investors are already actively looking to invest: several American funds are working in Ukraine to invest in local private defense companies.

Ukraine is trying to help local manufacturers in every possible way. For example, a special cluster, Brave1, was created: teams that present new products at different stages of readiness can receive grants or other funding, expertise, and opportunities to test their projects and receive feedback from the military. If the project works, Brave1 will help with obtaining contracts and finding investors.

That’s how the ShaBLya system came into being. It’s a robotic platform—a remotely controlled fire complex. Equipped with inspection cameras, a thermal imager and a rangefinder, it can detect targets at a distance of up to 5 km. The complex allows to protect Ukrainian soldiers on the frontline.

It is thanks to such state initiatives that Ukraine was able to scale up the production of drones, and today, it has moved on to a new direction—robotic systems and electronic warfare. It was thanks to Brave1 that it was possible to put into use the near-action electronic warfare, the so-called trench electronic warfare, which has already been transferred to the front in the amount of 2,000 units. Before the start of the full-scale invasion, such means did not exist in Ukraine.

How can you support Ukrainian arms manufacturers? The easiest way is to donate to Ukrainian initiatives that have permission to purchase weapons and ammunition: they do this mostly from Ukrainian manufacturers, providing them with work, and the military with weapons.

In two years of full-scale war, Ukraine has been able to multiply the production of different weapons: armored vehicles, drones, robots, and missiles. They are not stopping at what has been achieved: two years ago no one even talked about a long-range missile of 700 km, today the project is under development. And the market itself has changed beyond recognition: it has not been so large since the times of the USSR. Ukraine simply has no other way out today: Russia invests in its defense complex dozens of times more, and the budget for the war is 38% of all budget funds or about $120 billion.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-ca1a63b87c648c14784932e034e42964.jpg)