- Category

- War in Ukraine

What Russian Occupation Is Really Like, According to Ukrainians Who Have Already Lived Through It

In the shadow of relentless shelling and under the iron grip of Russian occupation, ordinary Ukrainians like Maria, Server, and Valentyn endure unimaginable hardships.

Maria learned about Russia’s full-scale invasion early in the morning of February 24, 2022, through a phone call from her parents, urging her to return to Vorzel, a village in the Kyiv region.

“We thought it would be safer there than in Kyiv, where I lived. Plus, we wanted the whole family to be together,” Maria explains.

What they didn’t expect was that Russian forces would occupy parts of the Kyiv region within the first days of the invasion, pushing their way toward the capital.

“It felt unreal that Russians would invade small towns like Bucha, Vorzel, or Irpin. No one had ever heard of these places, and now they’re on the front pages of the world’s most famous magazines,” Maria tells me.

Many Kyiv residents made similar decisions, leaving the city to stay with relatives or friends in nearby cities and villages, hoping these areas without high-rise buildings would be safer.

By February 26, 2022, Russian forces reached Maria’s village, Vorzel, along with Hostomel, Borodyanka, and Bucha. Residents watched as Russian paratroopers landed at Antoniv Airport, sparking a battle that ended with the airport falling into Russian hands. Soon, a significant part of the Kyiv region was under occupation.

Just over a month later, on April 2, Ukrainian Armed Forces liberated the Kyiv region. The retreating Russians left behind destroyed homes and shattered lives.

Struggle to survive

Life under Russian occupation resembles an open-air prison, where freedom is extinguished, dissent is crushed, and any expression of pro-Ukrainian sentiment risks severe punishment.

“I watched my dad persistently erase the sticker with the Ukrainian coat of arms from his phone that had been there for like 20 years—it hurt so much,” said Maria, describing how her family removed Ukrainian symbols from their home and personal belongings to avoid provoking the Russians.

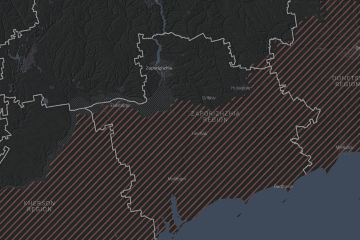

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Russia has seized control of an additional 11% of Ukraine’s territory, adding to the 7% it occupied since 2014. As of August 2024, 27% of Ukraine remains under occupation, according to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. This includes Crimea and areas in the Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions.

For many in these areas, daily life has become a relentless struggle to survive under constant threats.

Accounts from liberated areas like Bucha, Irpin, and Izium reveal the grim reality of life under Russian control. People endure the destruction of their homes, the disappearance of loved ones, and the constant fear of violence. Basic necessities like food, water, and electricity are scarce. Communities are isolated, cut off from reliable information, and silenced by the risk of imprisonment or worse.

From the first day of the occupation, life for Maria and her parents became a struggle. First, they lost electricity. Then phone and internet connection. It was winter, and the temperature in their home dropped to 10°C.

“We didn’t leave the house. We had no idea what was happening outside. We found ourselves in complete information isolation. Communication was rare and only possible in a certain part of the house,” Maria describes.

With no way to replenish supplies, food spoiled quickly, but they had to eat it regardless. “I already have issues with food, so forcing myself to eat spoiled food was disastrous for me,” she shares.

Water was strictly rationed. “We only flushed the toilet in emergencies. I bathed only twice in two weeks,” Maria recalls. “I started menstruating within the first few days. Luckily, my mom had pads, but there was no way to take a proper shower—only wet wipes.”

All this unfolded amid constant explosions and the roar of airplanes.

One day, while looking out the window, Maria saw a Russian tank marked with the letter “V” parked in front of the house. The soldier inside spotted her and aimed the tank’s barrel directly at her.

I instinctively hid behind the wall. Eventually, I stopped believing we’d ever get out of there. The only thing I feared was dying in agony under the rubble or being raped

Maria

Two weeks later, the first official green corridor for civilians opened in Vorzel. Maria’s family decided to take the risk, unsure if they would make it out alive or ever see their home again.

It was only at Russian checkpoints that the family realized their village was fully occupied. They later learned that their part of Vorzel, divided by a railway bridge, had remained relatively calm because it was difficult for large military equipment to access.

Another part of Vorzel, like the neighboring towns of Bucha and Irpin, suffered far worse. Bucha, in particular, later became internationally known for the atrocities committed by Russian soldiers there, now widely referred to as the Bucha Massacre.

“Every family’s experience of occupation is different. There are no identical stories,” Maria reflects.

“Your experience of occupation depends entirely on the occupiers. If they want to claim the territory as theirs, they’ll try to win over the locals. The occupation in the Kyiv region was different. It was simply an obstacle to Kyiv that they needed to clear and pass.”

Targeting civilians

In Kherson, a major city in southern Ukraine that fell under Russian occupation, the invading forces initially portrayed themselves as a "kind" army.

“They came as liberators. They smiled at locals and assumed we were happy to see them. But we stayed silent and kept to our homes”, says Server, 37.

Speaking out could mean being taken to a basement—and after that, you’d never know what might happen.

Server

Server, his wife, and their newborn child spent nearly nine months in occupied Kherson until its liberation. Unlike Vorzel, basic services in Kherson—electricity and stores—remained functional, but prices skyrocketed, and essential medicines were scarce.

Despite the challenges, Server refused to leave, unwilling to abandon his elderly mother and the house he had spent years building.

“I had my wife, newborn child, and our dream house. We were supposed to live there,” he recalls.

When Ukrainian forces liberated Kherson, Server’s relief was short-lived. “We couldn’t believe it was true. But our happiness ended within a day,” he says.

Russian forces began relentless shelling, targeting civilians. Server’s house was destroyed, forcing his family to relocate to Mykolaiv.

Valentyn, 60, stayed home in Kherson with his wife, sister, and daughter for as long as possible, but their house was also destroyed shortly after liberation.

Everything burned down. My house, my son's house, and my sister's house—completely destroyed. There’s nothing left and nowhere to return to. Fortunately, my entire family survived. Now we rent an apartment.

Valentyn

Life in Kherson has only worsened. Since mid-2024, Russian forces have intensified their attacks on civilians using killer drones. They have launched over 9,500 attacks on the city and surrounding villages, aiming to depopulate the area entirely, according to local officials.

“The killer machines, sometimes by the swarm, hover above homes, buzz into buildings, and chase people down streets in their cars, riding bicycles, or simply on foot. The targets are not soldiers or tanks, but civilians,” wrote The Financial Times in a December 2024 investigation documenting the use of drones by Russian forces to kill civilians.

Local resistance

Some Ukrainians in occupied territories have become the eyes and ears of the military, playing a critical role in Ukrainian strikes against Russian forces.

Server was one of those people. Using access to city surveillance cameras, he streamed footage for Ukrainian forces. When asked for views of the Antonivka Road Bridge—a vital Russian supply route—he ventured out at night to install cameras himself.

Later, the Ukrainian Armed Forces destroyed the bridge, and the video from the cameras circulated widely on local Telegram channels. “Ukrainians were thrilled and shared the video massively, but they didn’t consider that the Russians would also see this video and start looking for the person who installed the cameras,” Server explains.

Risking his life again, Server ventured out during curfew with a creaking ladder to remove the cameras. Just two days later, drones flew over his home, followed by a visit from Russian forces.

“They introduced themselves as military police, checked my personal cameras, found nothing, and left,” Server recalls. “If they had found any evidence, I wouldn’t be here today.”

When Ukrainian soldiers asked him to reinstall the cameras, Server refused. “Someone had carelessly posted the camera footage online, and it could’ve cost me my life if I hadn’t taken them down immediately,” he says.

Acts of resistance often come at a heavy price. Those caught aiding Ukraine are sent to Russian torture chambers, with no records of their release.

Over 139,000 Russian war crimes have been documented, Prosecutor General Andrii Kostin said in September 2024, though the full scale of atrocities in still-occupied areas remains unknown.

Life after occupation

Those Ukrainians who survived the occupation continue to grapple with its aftermath.

“In such extreme conditions, the scariest thing is accepting the possibility that you might not make it out alive,” Maria shares. “Unfortunately, that happened to me. My mind adapted in a way that I had to convince myself every day that tomorrow is possible, that tomorrow has meaning, and that it’s not my fault I survived.”

Maria also faces psychological challenges from unexpected triggers. “When we first arrived in Kyiv, I saw a pile of avocados at the grocery store, and it made me feel awful. It reminded me of how I used to eat them rotten at home, as there were no other options,” she says.

For Valentyn, a man from an older generation, processing the psychological toll of war is less of a priority. His response took the form of physical resistance. Shortly after Kherson’s liberation, he joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

“What else could I do? My son is fighting, so I went to fight too—for my land, for Kherson,” he says.

A year later, Valentyn was discharged due to his age—he had turned 60, the official age limit for serving in the military. He then joined the emergency services as a machine operator, driving heavy equipment.

“Not long ago, I was concussed again. Somehow, I survived. It feels like I was born under a lucky star,” he says.

“Before every mission, I cross myself. It’s terrifying, really terrifying. But I have to help our guys. So many of them have fallen, and there’s no turning back.”

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)