- Category

- World

Iran Attacked Israel with Shahed Drones. Ukraine Has Already Faced Them—Because of Russia

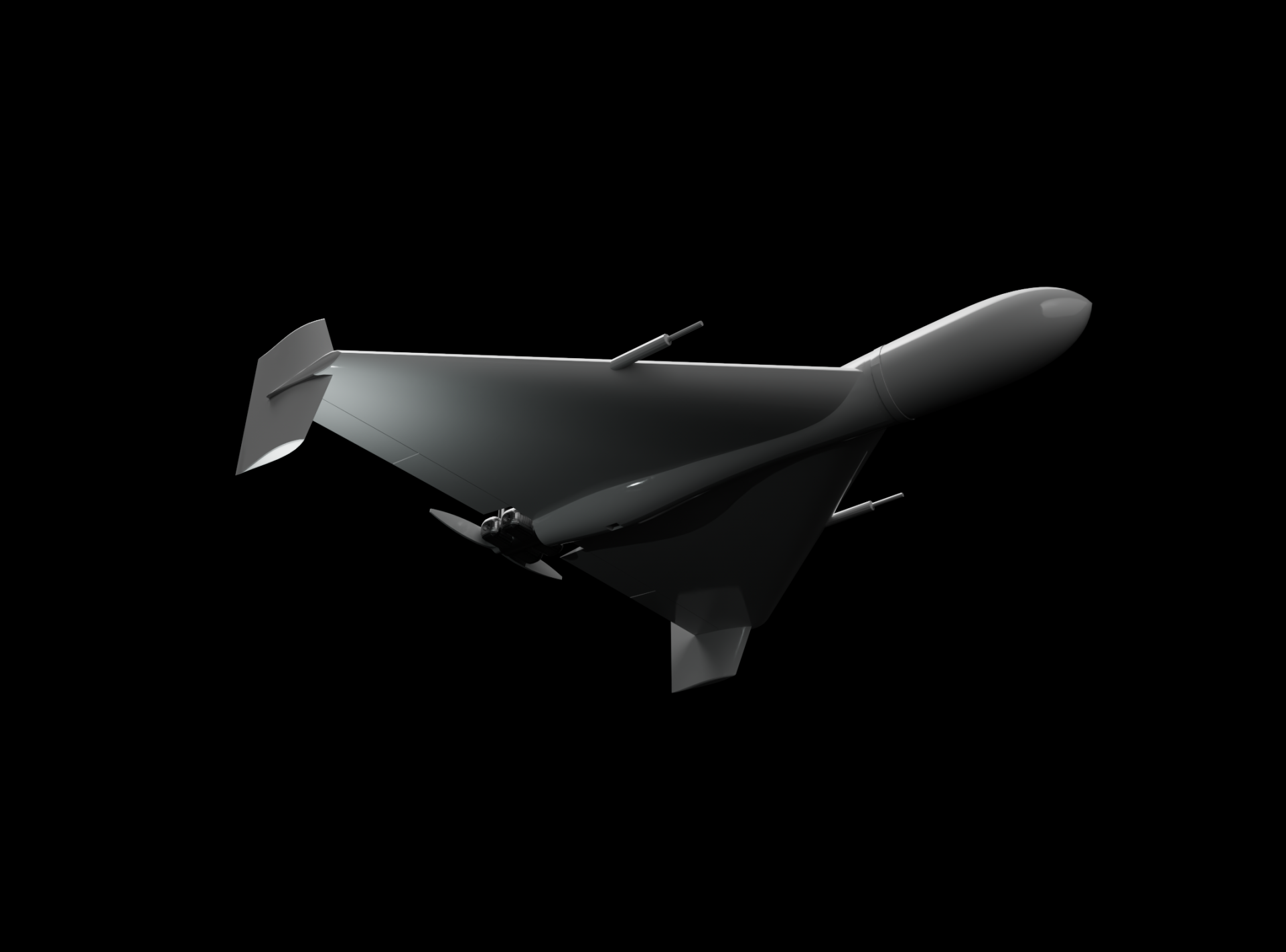

Iranian Shahed drones are cheap, fast, and deadly. But it’s not just Iran that uses and produces them, it’s also Russia—giving Ukraine plenty of opportunity to get pretty good at shooting them down. But how are they made? How much damage do they cause? And why are they used so widely?

On the night between April 13th and April 14th, Iran launched 300 missiles and drones—including 170 Shahed-136 kamikaze drones—at Israel. News of the attack quickly travelled the whole world, but there was one particular country that already knew—all too well—what the Iranian drones sounded like.

Since September 2022, Ukraine has been under constant bombardment by the Shahed-136 kamikaze drones, which Iran began supplying to Russia in exchange for money and assistance with its nuclear program. Since then, around 4,900 of them have been launched by Russia against Ukraine—sometimes 600-700 in just one month. In the first two weeks of April alone, Ukraine was attacked by 236 Shaheds. Russia has even built its own factory that produces hundreds of them each month.

On average, Ukrainian forces shoot down about 80-90% of all drones that come in, sometimes increasing this figure to 100%. However, Russian attacks with Iranian drones often lead to the destruction of civilian houses and critical infrastructure—such as ports and power plants. This is a direct violation of the Geneva Conventions, to which the Russian military seems to pay little attention.

We look into what is known about these infamous Iranian drones, how Western companies help in their production, and how Ukraine has learned to fight them.

Shahed-136: It’s costs and technical specifications

Iran introduced the Shahed-136 drone in 2020. Developing relatively inexpensive drones capable of causing significant damage is part of Iran's military strategy: they can mass-produce them and deploy them against key adversaries in the region.

In its early versions, the Shahed-136 could cover distances of up to 2000 km at speeds of 150-200 km/h, carrying an explosive payload. While it's not a cruise missile, the drone can still inflict considerable damage. For example, it can easily destroy parts of a residential building.

Overnight, Russia fired more than forty missiles and about forty drones at Ukraine.

— Volodymyr Zelenskyy / Володимир Зеленський (@ZelenskyyUa) April 11, 2024

I thank everyone engaged in recovery efforts after the attack, as well as to every warrior of our air defense system who was on guard last night.

Some missiles and "Shahed" drones were… pic.twitter.com/Oxk78LTVj6

Its biggest advantage is its price. According to estimates, cited by The Guardian and many other Western sources, the cost of one drone could be just over $20,000. Military.com claims that the assembly cost of one of them in a Russian factory is around $50,000. Most experts point to a similar price range.

However, the low cost is only advantageous to those deploying the drone. It's a different story for those defending against it.

For instance, with the increased military activity of the Yemeni Houthis in the Red Sea, allies had to secure shipping through the Suez Canal. To do so, they had to shoot down drones and missiles at a cost exceeding $1 million per target. What if they didn't do this? The losses would have been colossal.

Ukraine has endured dozens of Shahed drone attacks by Russia. When air defense systems were lacking, they targeted residential buildings. One of the first instances of these attacks was in the fall of 2022—when they hit Kyiv. But Russia keeps using Iranian Shahed drones against civilians in Ukraine even today. At the beginning of this month, a Shahed drone hit a residential house in Kharkiv and killed a woman. A week later, a multi-storey block—home to many people—went up in flames in Odesa. There, another Shahed hit a logistical center—causing a fire. Ukrainian cities have been under attack from these drones for over two years now.

In 2023, the target shifted to port infrastructure on the Danube River. Ukrainian companies relied on these ports as almost the sole means of exporting grains to external markets—as Ukraine ranks among the top global grain exporters. Successful Russian attacks with Iranian drones led to losses in the tens of millions of dollars and increased freight costs for maritime transport.

Yet, Ukraine learned to combat them with whatever means it had.

Ukraine’s mobile air defense groups

The first Russian attacks with Shaheds on Ukraine were a surprise and caught Ukrainian Air Defense Forces off guard: such weapons had never been used before on this scale anywhere in the world. In addition, there was a shortage of air defense missiles. That is why it was necessary for Ukraine to quickly find a solution that could address several problems at once:

The solution had to be affordable. Expensive air defense missiles were not an option.

The solution had to be mobile. Drones are launched in waves, in large numbers at once, and they fly in different directions. Air defense units must be able to redeploy quickly.

The solution had to be usable in different locations: both in large cities and to protect isolated ports.

Shahed isn't a high-tech weapon; so it was discovered that it can be shot down even with small arms. However, military officials immediately warned civilians against attempting to shoot down drones with their own weapons due to the risk to bystanders.

Ukraine quickly established special mobile groups capable of shooting down Shaheds and protecting critical infrastructure and cities.

A regular vehicle—like a pickup truck—equipped with a spotlight, radar, targeting systems, and a machine gun manned by several crew members, transforms into a group capable of rapidly responding and neutralizing detected Shaheds.

Despite Shaheds being fairly well-equipped with electronic warfare countermeasures, successful cases of using electronic warfare against these drones have become increasingly common in Ukraine. There are now plenty of photos of downed Shahed drones lying in Ukrainian fields.

Yes, it is easier to shoot down a Shahed drone than a hypersonic missile. But these drones remain an extremely dangerous weapon used by Russia to attack Ukraine. Moreover, their use on the battlefield persists because their main advantages include price, production speed, and effectiveness.

For instance, Russia can only produce a few dozen missiles a month. But it is set to produce over 2500 Shaheds a year. At maximum capacity, the Russian factory can assemble up to 10 Shaheds a day. These then become helpful tools for the few but highly dangerous Russian missiles.

Often, Russia launches combined attacks, as was the case with Iran and Israel. They launch drones, cruise missiles, and Shaheds from different directions simultaneously.

They deploy dozens of drones at once, overwhelming the air defense system, and thereby clearing the path for missiles to reach their targets. Ukraine has limited resources for air defense systems, so the more force Russia throws at it, the harder it is to repel these attacks.

Ukraine has a vast territory, roughly 25 times larger than Israel, and must find the most effective ways to defend it. In current conditions, that’s extremely challenging. During one of the recent attacks, the largest power plant in the Kyiv region—Trypilska thermal power plant—was destroyed simply because the region ran out of missiles to defend itself.

So what can be done?

Shahed drones may appear to be simple weapons. But they can actually cause significant damage and pose a threat to both civilians and critical infrastructure, like power plants or gas extraction facilities. These powerful kamikaze drones can reach their targets and cause significant destruction—if there is no adequate air defense to stop them. Additionally, they are evolving: Ukrainian forces are constantly seeing improvements in navigation, speed, and flight range. Upgrading air defense systems is one way to protect countries from them. But it is also necessary to ensure that those who can produce them, such as Iran and Russia, are simply unable to do so. Because new targets may emerge soon.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-320fa9b844a6c2e67232a20475191407.webp)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)