- Category

- Anti-Fake

5 (Uncomfortable) Questions For the Russian Opposition

“What is Europe’s strategy towards Russia?” asks one of the Russian opposition leaders, Yulia Navalnaya, in a column for The Economist. Yet each time a Russian opposition figure publishes another text or delivers another speech, one question inevitably arises: what exactly is the Russian opposition’s own plan for Russia?

Familiar narratives from those who claim to oppose Putin’s regime continue to circulate: “you can’t equate Russia with Putin,” “not all Russians are guilty,” and so on. Yet with no clear understanding of what most Russian opposition leaders actually say or do beyond such statements, it is time to ask at least a fraction of the questions one would ask of any group that calls itself an opposition to a bloody regime waging wars of aggression against its neighbors, including a full-scale invasion of Ukraine for nearly four years.

As Navalnaya herself wrote in her column, “the absence of a longer-term strategy would carry disastrous consequences.” But if the Russian opposition hasn’t clearly answered even the most basic questions about its own actions in that regard, what kind of long-term strategy can we possibly talk about?

What is your real plan to get into the “Russia after Putin”?

Many Russian opposition figures publicly argue for a “future without dictatorship,” but few have published detailed, public roadmaps explaining how that would be achieved. Analysts and policy outlets report that the opposition is fragmented in exile and focused on advocacy, declarations, and humanitarian projects rather than a unified operational strategy for regime change.

Much of the Russian opposition’s activity still takes place abroad—at conferences, in interviews, or through declarations directed at Western audiences. Inside Russia, their presence and influence remain limited, partly due to repression, but also because no coherent framework for political change has emerged. For some, the hope seems to rest on the eventual collapse of Putin’s regime rather than on an organized effort to bring it about.

This raises a broader question: if the opposition’s main vision is confined to imagining what life might look like after coming to power, how much confidence can anyone have in its ability to get there? As opposition that has no action plan looks more like a set piece.

What exactly have you done in nearly four years of Russia’s full-scale war?

Hundreds of thousands dead, millions displaced, torture chambers, deportations, kidnapped children, Mariupol, Bucha, Izium—the list is long and devastating. The question is: how exactly have Russian opposition leaders helped to stop this?

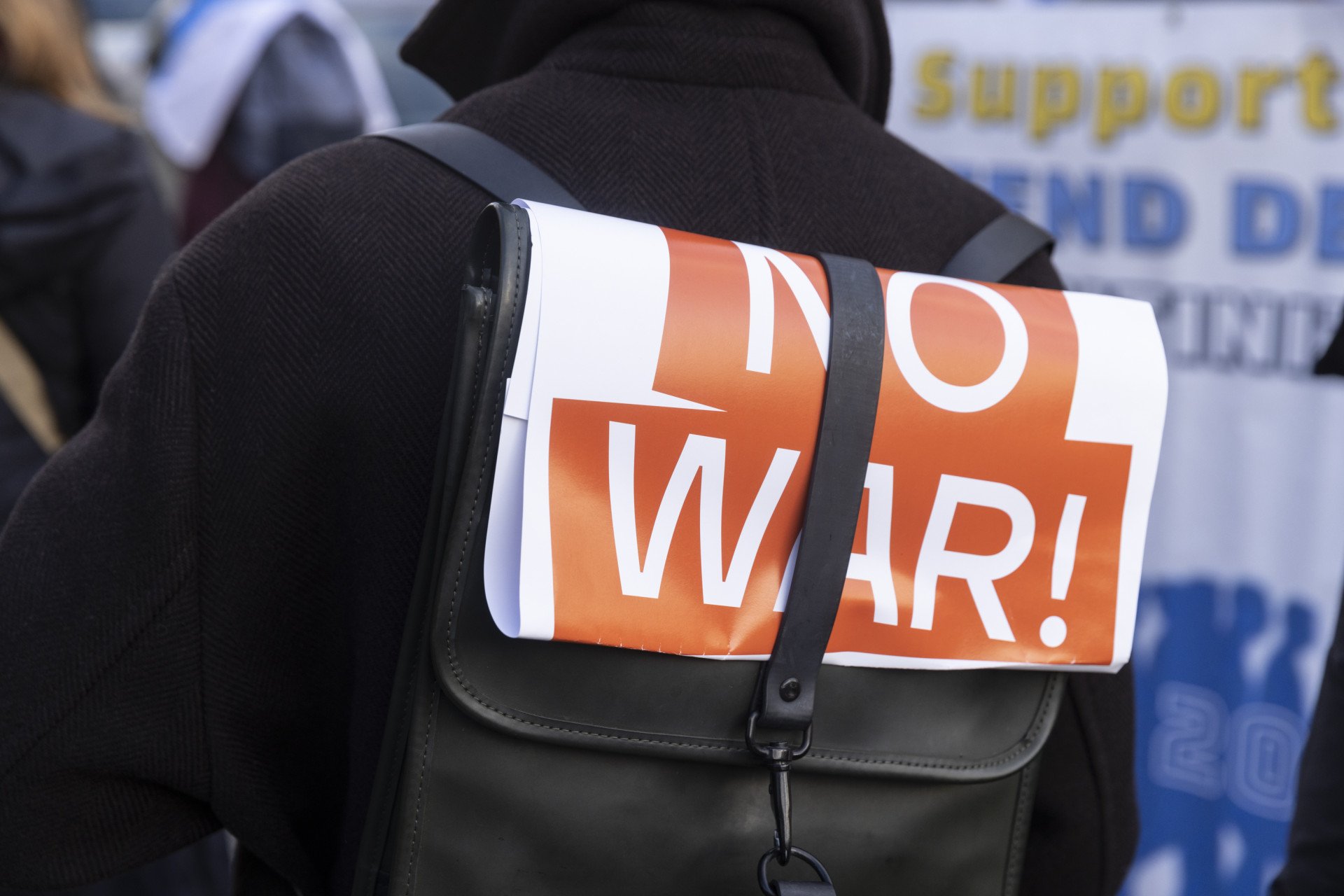

Symbolic acts like putting up posters, moving abroad, and running media platforms may have moral value, but without concrete results, they raise doubts about real, measurable impact.

For example, the best-known grouping, the Russian AntiWar Committee, brings together exiled figures such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Garry Kasparov. Its most visible initiatives include public declarations, assistance to Russian refugees in Europe, and limited humanitarian support for Ukraine through the delivery of medicine and portable power stations. The Committee itself states that it was created to “develop a common stance and help address the consequences of Putin’s aggression,” calling it a civic duty to “do everything possible to stop it.”

Yet a central question remains: can these actions meaningfully accelerate the collapse of Putin’s regime?

After more than ten years of war—four of them full-scale—there is still no unified, powerful oppositional structure openly urging Russians to take domestic action: to resist, to refuse taxes, to boycott state companies, leaving it to smaller, decentralized or semi-public movements.

Does the Russian opposition work to help Ukraine win?

If you are not helping to bring about the aggressor’s defeat—you are prolonging the war.

Russian opposition figures rarely speak about the Ukrainian victory. As Kasparov himself once said, “You never hear Russian opposition actually say Ukraine must win.” The very word victory is often avoided. Many understand why: Ukraine’s victory would mean not only the fall of Putin’s regime but the collapse of the imperial mindset that has shaped Russian society for generations.

So instead of genuine support, Ukrainians hear: “You shouldn’t support those who also hate Russians.”

If we imagine these words coming not from opposition figures but from Putin himself, they would sound entirely natural—because, in truth, this is not a position of opposition at all, but an echo of Putinism spoken in a softer tone.

Moreover, when Navalnaya was asked whether Western countries should supply weapons to Ukraine, she replied: “It’s hard to say. Vladimir Putin started the war, but the bombs also fell on Russians.”

And how often have you heard of well-known Russians organizing fundraisers to support Ukraine’s Armed Forces? Or even for their own compatriots fighting against “Putin’s army” in Ukraine—the Sibir Battalion, the Russian Volunteer Corps, or the Freedom of Russia Legion?

Can you plainly say: Russia is the aggressor?

The war began in 2014. Crimea is Ukraine. Russia commits war crimes and crimes against humanity. All of these are simple facts.

Yet even these basic truths often provoke discomfort among Russian opposition figures. The responses are familiar: “The Crimea question is complicated.” “It’s not that simple.” “We’ll need to negotiate.”

At a notable press conference held by recently released opposition leaders—Vladimir Kara-Murza, Ilya Yashin, and Andrei Pivovarov—there were no mentions of reparations, responsibility, or justice for the victims of Russia’s war crimes.

Once again, it is an avoidance of truth. Any clear acknowledgment of aggression threatens the Russian opposition’s moral comfort zone: to admit a crime is to accept responsibility. Whatever version of a “New Russia” they may speak of, one thing remains constant—the absence of accountability for the past and present actions that Russians have inflicted upon millions in their neighboring country.

How do you plan to work with a Russian society that supports the war?

As the Russian opposition leaders often talk about the Russian population, it is important to understand what they actually mean. Yashin and Kara-Murza urge the world “not to equate the Russian people with Putin’s regime.”

The majority of Russians do not exhibit horror or resistance—they support the invasion, with a big and active part rejoicing at Ukrainian deaths and approving the bombing of peaceful cities. In the summer of 2025, 74% of Russians supported the war against Ukraine, according to the Levada Center.

So the question is: what does the Russian opposition plan to do with a society it failed to reach during all these years?

Are there any preparations for tribunals, for lustrations, for a break with this “past”? Without it, there will be no “new Russia” to dream of. There will be only the old totalitarianism under a new brand—more palatable to the West, but no less dangerous to its neighbors.

The Russian opposition often speaks the language of morality but seems to fear its logic. It mainly calls for “not hating all Russians,” but it does not explain how to stop a population that kills on a massive scale. It dreams of returning Russia to the civilized world, but does not say what actions it is willing to take to achieve that.

Today, the West again risks opening the door to Russia—this time under the cover of the opposition. But the focus must stay on responsibility first.

Before inviting the Russian opposition to the table once more, these questions must be answered. And if there is again no answer, perhaps there’s nothing to bring to the table as well.

FAQ

Who is Yulia Navalnaya?

Yulia Navalnaya is the widow of Alexei Navalny, the late Russian opposition leader who died in prison in 2024. Since his death, she has become one of the most visible figures in the Russian opposition abroad, calling for Western countries to develop a long-term strategy towards “Russia after Putin.”

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)