- Category

- Anti-Fake

Putin’s Press “Freedom” Goes Even Deeper Into Authoritarian Decline

Putin claims that Russia has media freedom. However, Russia is one of the world’s worst countries for that. What are the facts? How does Russia restrict information sharing, and what punishments are journalists and civilians facing?

“The media in Russia is free,” Putin said on Monday, August 2nd, 2024, during his visit to Mongolia. “The only requirement for [media outlets] is compliance with Russian legislation.” He also claimed that the West is openly persecuting Russian journalists.

These statements come just days after Russia banned more than 92 American citizens from entering Russia, including journalists from The Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and New York Times.

Press and media freedom is plummeting in Russia since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. More restrictive laws have been put in place, and journalists are being increasingly persecuted.

In contrast to Putin's recent statement, Russia is ranked as one of the world’s worst countries for press freedom. Russia is ranked 162 out of 180 countries globally, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

Almost all international independent media have been banned, blocked, and/or declared as “foreign agents” or “undesirable organizations.” Journalists are being charged with espionage, treason, extortion, spreading fake news about the Russian Army, and more, leading to lengthy prison terms.

Freedom House ranks Russia with 13 points out of 100 and lists the country as “not free.” Russia has 21 points out of 100 for “internet freedom.” 1 of 100 within the “nations in transit” ranking, putting Russia at a consolidated authoritarian regime status. 100 points within these rankings is the highest level of freedom, with one being the lowest.

On May 3rd 2024, World Press Freedom Day, the US Embassy and Consulates in Russia stated that it was a particularly “somber day in Russia, where freedom of the press is under constant assault.” They condemned Russian authorities’ for their continued “attempts to silence, intimidate, and punish journalists, and to sever their connection with civil society.”

Currently, there are 34 journalists and six media workers detained in Russian prisons. Twelve of them are serving prison sentences ranging from five-and-a-half to 22 years in prison, according to the United Nations Human Rights Council.

OVD Info states that 58 Russian journalists have criminal proceedings against them. They are either currently imprisoned, wanted, or due to appear in court.

Ukrainian Journalists Persecuted by Russia:

In June 2024, at the “Journalists Matter: a call to free Ukrainian journalists held in captivity by the Russian Federation” event, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) stated that at least 100 journalists have been taken hostage by Russia since 2014, when Russia’s war in Ukraine began.

According to monitoring "Freedom of Speech Barometer" by the Institute of Mass Information (IMI), in the first two years and four months of the full-scale invasion, 602 crimes were committed against journalists and media outlets in Ukraine.

IMI reported that 82 journalists have been killed, 10 of which were killed while performing editorial assignments. 14 journalists are missing and 27 kidnapped. There have been 69 death threats and intimidation of journalists. 20 Ukrainian editorial offices have been seized by Russian forces, 235 Ukrainian media outlets have been shut down and much more.

Russia’s crackdown on dissent:

Since the full-scale invasion, the Kremlin has cracked down on dissent in Russia, targeting anyone showing support for Ukraine, not only journalists, but civilians too.

During the first two years of full-scale war, from February 2022 to February 2024 there were 19,850 detentions for anti-war stances, with 15,355 of them occurring in the first month alone.

There are currently over 1000 people accused on various charges from treason to terrorism for supporting Ukraine in some format, with almost 300 people already in pre-trial detention centers or in penal colonies.

Criminalizing poetry and memes:

In December 2023, two Russian men were imprisoned for reciting anti-war poetry in what Russian authorities said was "undermining national security” and “inciting hatred”. Artyom Kamardin was sentenced to seven years, and Yegor Shtovba to five-and-a-half years in prison.

Even before the full-scale invasion Russia was imprisoning people for sharing memes. In 2018, Maria Motuznaya faced up to six years in prison for sharing a variety of memes. One being an image of nuns smoking with the caption “Quick while God isn’t looking”. Back then, most criminally punished meme sharers religion based, now, it’s Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In August of this year, Russia sent Usman Baratov, the head of an Uzbek diaspora group to four years in prison for “inciting hatred”. The meme he shared joked about Russia's rising inflation and military mobilization. The meme showed a hen in a chicken coop with the caption: “Screw you and your eggs! Bring the cocks back from the front.” Prosecutors have requested an increase for a maximum sentence of six years in prison.

Criminalizing anti-war graffiti and stickers :

In April 2024, two teenagers were imprisoned over anti-war graffiti they’d painted. Aleksandr Snezhkov, 19, and Lyubov Lizunova, 16, were sentenced to 6 years and 3 1/2 years in prison, respectively.

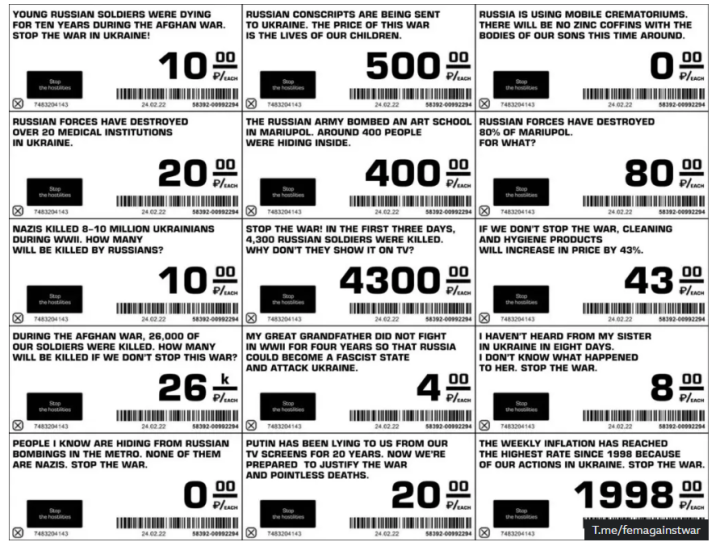

In November 2023, artist Sasha Skochilenko was sentenced to 7 years in prison for replacing price tags with anti-war stickers in local supermarkets. In June 2024, she was freed in one of the largest US-Russia prisoner swap in post-Soviet history.

Reporting on Ukraine’s recent incursion of the Kursk region:

The Ukrainian army began its incursion in the Kursk region on August 6th, 2024. Russian authorities have started criminal proceedings against seven journalists who covered the incursion in the western town of Sudzha. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJs) condemned the criminal investigations opened against them.

“The prosecution of the journalists covering an important development in the Russian-Ukraine war is another assault on press freedom,” said Gulnoza, CPJs, New York coordinator.

The media outlets being investigated by Russian authorities are Deutsche Welle, “1+1” national Ukrainian TV channel, CNN, Hromadske, Washington Post, and journalists from Italian public broadcaster RAI. According to the Russian criminal code, their journalists could be charged with up to five years in prison and would be placed on an international wanted list.

What are “foreign agents” and “undesirable organizations”?

According to RSF, a third of the victims subject to Russia's “foreign agents” law are independent media outlets. At the end of July 2024, almost 300 media outlets were on the list. For example, the Russian edition of the German newspaper Bild was also added at that time. The media sector is three times more persecuted under this law than the second sector on the list—“political entities.”

The designation of a “foreign agent” can be given to any individual or legal entity who participates in any foreign political or “other” activity. If they receive foreign support or “fall under foreign influence in other ways.” This vague definition was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights in June 2024.

Those placed on the list are closely monitored, controlled and must label every piece of text, audio or video output with the words “foreign agent” in a font that is twice the size of the rest of the content.

Moscow bookshelves today. Books by the best Russian authors are marked "FOREIGN AGENT" because the authors spoke against the war. A fascist practice that we watch live, not in a historical documentary. pic.twitter.com/CvIRENDQCr

— Konstantin Sonin (@k_sonin) December 4, 2022

More than 20 media outlets have been listed as “undesirable organizations”; over a third of them are dedicated to investigative reporting. They are officially defined as foreign organizations that pose a “threat to Russia.”

They are exposed to criminal prosecution and face up to five years in prison, amongst other restrictions. At the end of July 2024, the state Duma expanded the scope of this law.

Some organizations have been listed as both undesirable organizations and foreign agents, such as Bellingcat, an organization of open source researchers and journalists.

Which media outlets are in Russian prison?

Last week, August 30, 2024, Russian journalist Sergei Mikhailov was sentenced to eight years in prison for “intentionally spreading false information” about the Russian army. He was arrested in 2022 for posting on a Telegram channel about the murder of civilians in Bucha and Mariupol. His defense is due to take the stand next week, September 2024.

In March 2024, journalist Roman Ivanov was sentenced to seven years in prison for criticizing the offensive in Ukraine in a social media post and spreading “false information” about the Russian armed forces.

"Peace and freedom," Ivanov shouted as he left the courtroom after the sentence, media reported. His supporters applauded and shouted, "We're with you. You are not alone."

In July 2024, Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was given a 16-year prison sentence on espionage charges. Gershkovich was a fully accredited journalist and US national who had been operating in Russia for a number of years.

Alsu Kurmasheva, Radio Free Europe (RFE/RL) reporter is facing a six-and-a-half year prison term and was charged with “spreading fake news about the Russian army”. She was detained particularly for her editing of the book “Saying No to War - 40 Stories of Russians Who Oppose the Russian Invasion of Ukraine”, published in November 2022.

On Thursday, August 1 2024, Gershkovich and Kurmasheva were both released as part of the largest East-West prisoner swap since the Cold War.

How does Russia control its narrative further than criminal arrests?

Wartime censorship has forced many independent Russian journalists to flee the country. However, Russia is still targeting journalists in exile. In January 2024, the Russian State Duma passed a bill for the confiscation of property for those charged with disseminating “fake news” about the Russian army.

When passing the bill, Russian MP Andrey Lugovoy said: “Fleeing the country is, of course, easy and pleasant (…). But we will not allow this situation. Anyone who tries to cause damage to their homeland, country, and citizens will lose everything and die there, outside our country, like the last dog.”

In March 2024, the Duma also placed a ban on companies placing ads on websites, social media such as YouTube, and other digital platforms run by “foreign agents.” This law cuts funding to independent voices critical of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Organizations in violation of these laws not only face fines but in some cases, prison terms too, tried in absentia.

Social media crackdown

The state Duma passed a bill requiring social networks with more than 500,000 daily users to hand over user data to the Federal Security Service (FSB) and Russian media regulator Roskomnadzor upon request. Any individual in Russia with over 10,000 subscribers on any social media platform must also register with Roskomnadzor.

According to Freedom House, telecommunications operators have been ordered to work more closely with the FSB. Fines would be given to operators who refuse to install the Technical Measures to Combat Threats (TSPU) system, which facilitates website blocking and surveillance. Increased fines would be given to those that still needed to install surveillance tools.

Roskomnadzor has blocked the messaging channel Signal, and preparations have begun to block WhatsApp. Pro-Kremlin media outlets have reported that YouTube will be completely blocked by September. The blocking of these channels is another restriction on free expression and freedom of information in the Russian government's sweeping crackdown.

According to Statista, in March 2024, television was noted as the primary source of national and international news for over 65% of Russians. Social media was the second most popular channel, with 38%. With the rise of internet usage, Russia focuses on censorship of social media to maintain information control. TV news mainly consists of pro-Kremlin propaganda.

Russia continues to restrict and oppress press freedom. Information sharing through social media may soon be in complete darkness. Journalists continue to be persecuted, and the lives of Ukrainian journalists and the foreign press continue to be at risk.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)