- Category

- Opinion

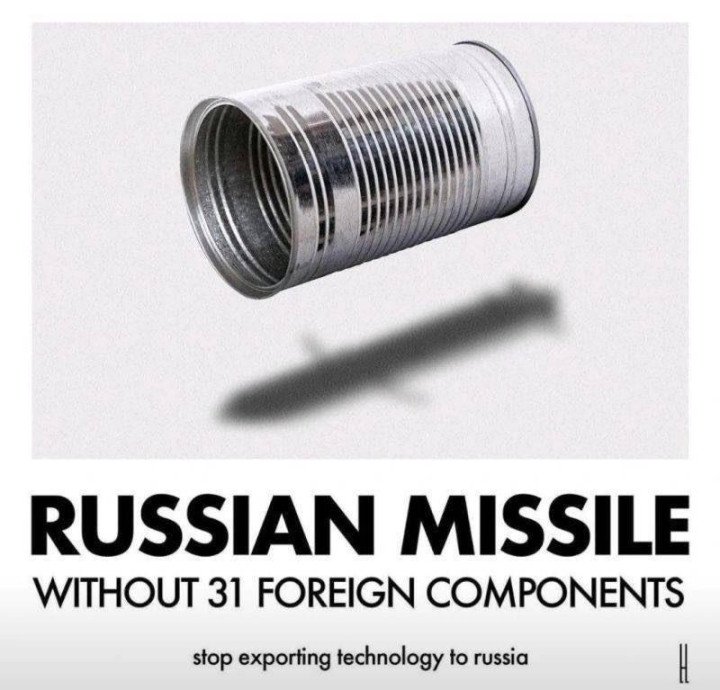

Western Components in Russian Missiles: How to Turn Enemy Weapons into Tin Cans?

Recently, I came across an image online that vividly illustrates what Ukraine and its Western partners should strive for today. 31 foreign components—this is just an example of the content of a single Russian Kh-101 cruise missile, which was used to strike Kyiv..

Experts from the defense analytical center Royal United Services Institute studied this missile. Russian missiles must be turned into tin cans, but for this to happen, arms manufacturers need to experience a "component famine"—a complete cutoff of access to Western microelectronics.

The weapons used by Russia – whether domestic, Iranian, or North Korean – can only hit their targets thanks to Western components. The "axis of evil" nations simply have no alternatives. As a result, these components are purchased from Western companies through complex routes, circumventing sanctions, sometimes costing tens of thousands of dollars. For example, the FPGA microprocessor is a critically important component for Shahed-136 drones, Iskander-M ballistic missiles, Tornado-S rocket systems, and more. The largest suppliers of FPGA are American companies, notably AMD and Intel. Despite company statements on halting exports since February 2022, their microchips continue to find their way to Russia.

Since 2022, NAKO has analyzed over 2,500 components found in 30 samples of Russian weaponry, including fighter jets, the Ka-52 "Alligator" helicopter, Kalibr missiles, and Iranian drones. 2,000 aircraft components were supplied to Russia from 22 countries, primarily Western. 64% of the parts came from companies headquartered in the USA.

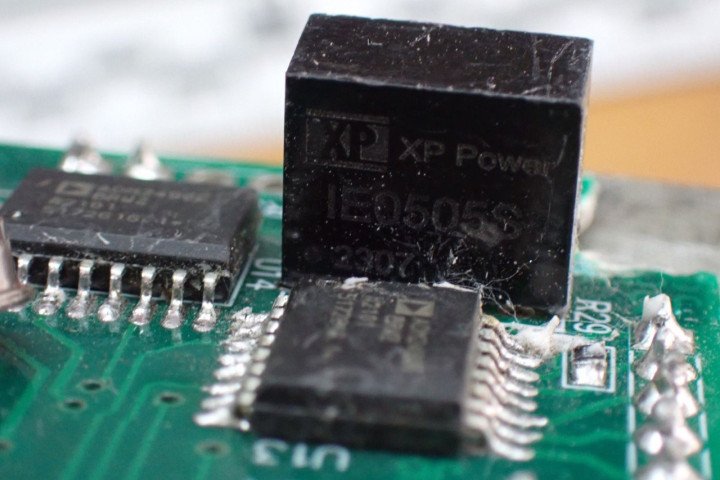

Our new analysis focuses on North Korean missiles. Several sources have confirmed that North Korea has joined the war in Ukraine both technically and personnel-wise. The KN-23/24 missile, which we analyzed, was shot down by Ukrainian forces in September over Poltava. It contains microelectronics produced by companies from the USA, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands in recent years.

Most of the microelectronic components are labeled with American company markings. These include microchips, the most critical part of any missile, used for navigation, control, and radio guidance of the weapon. In addition, we found electrical transformers, diodes, transistors, light-sensitive semiconductors, and, most importantly, programmable integrated circuits in the North Korean missile.

All analyzed components are subject to export control systems imposed on Russia after its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Similar, though not identical, restrictions had been in place against North Korea long before. For example, in the North Korean missile, we found a microchip manufactured in 2021, falling under the first level of export control classification developed by the USA, UK, Japan, and the EU against Russia. This microchip is also a strategically important component under the separate U.S. export control framework.

Russia, North Korea, and Iran exchange not only weapons but also technology. Their scientific and industrial cooperation is growing, and it could threaten Western countries shortly. So far, manufacturers of critical technologies bear no responsibility for the fact that their products end up in Russia.

Iran has been under sanctions for over 30 years but still managed to produce Shahed drones, sometimes using engines stolen in the early 2000s. North Korea has been under sanctions for many years but received chips manufactured in 2023 and will most likely get 2024 chips. Therefore, entirely restricting the flow of microelectronics to authoritarian countries is impossible. We can only make these processes more challenging for them.

The U.S. and EU governments must more rigorously monitor their sanctions policies and coordinate the imposition of sanctions. Microelectronics manufacturers must improve control over the movement of their products beyond their own countries. Law enforcement and financial institutions in the U.S. and EU must actively investigate violations and prevent the sale of microelectronics to sanctioned countries.

After our analysis was published, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andriy Sybiha called on allies to "respond decisively, tighten sanctions, and strengthen export controls." Will there be a Western response? We can only hope.

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-da3d9b88efb4b978fa15568884ef067f.jpg)

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-f3bede69822b36ac993a6cd5b65014f9.png)