- Category

- War in Ukraine

24 Hours With the Frontline Surgeons Saving Ukrainian Soldiers

Every night and day, surgeons from the 3rd Army Corps’ 4th Separate Medical Battalion race against time to save the lives of fellow soldiers. Our team spent 24 hours with them, sharing their grueling routine and their relentless fight to deal with the gruesome consequences of war.

Warning: The following content contains graphic descriptions and images of amputations, which some people may find distressing.

The medical point’s door suddenly slammed wide open. A few soldiers rush in, surrounded by medics pushing two gurneys into the corridor.

“First room, first room!”

An exploded foot, looking like a bloody, dripping flower, protrudes from under the first foil blanket, bones exposed like some eerie, surrealistic painting. On the other side of the blanket, Didenko, in his twenties, stoically grits his teeth.

The other soldier, half-conscious, lets escape the rattles of pain. His entire face is riddled with shrapnel, and his body is an open wound.

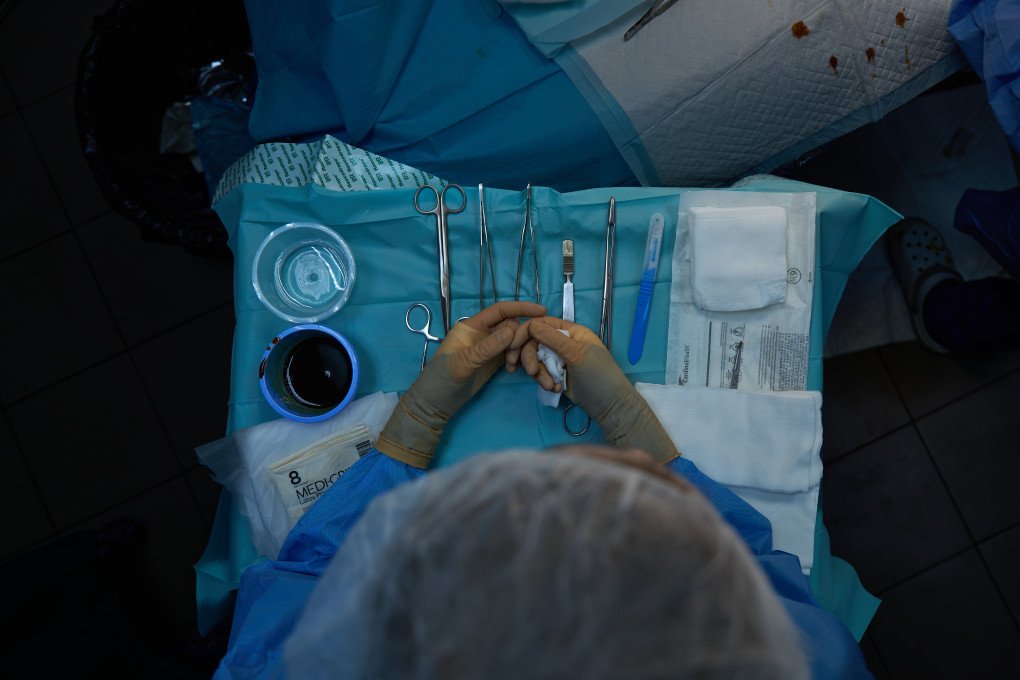

“Let’s clean everything, and get the bloc ready!” says “Luher,” a traumatologist and surgeon operating here.

Here, in the 3rd Army Corps’ 4th Separate Medical Battalion’s medical point, even the surgeons have callsigns.

They only have five to ten minutes to make a fateful decision that will save these soldiers' lives and change them forever.

Clothes off, painkillers and oxygen in, once the diagnosis is done, the cohort heads right to the operation block, where the surgeons’ team, helped by an armada of nurses, will do everything in their power to keep the heavily wounded alive before they can be taken to further from the front.

“The main injuries come from FPVs and mines, but the main issues are often that we need to clean the wounds properly because there can be mud, grass, or dirty shrapnel in wounds that lead to infection,” Luher says.

Once the diagnosis is done, it’s time to clean and amputate if needed. In this medical outpost, these operations are a matter of life and death.

War surgery and deadly tourniquets

Ukraine’s frontline has become a testing ground for a new kind of war surgery, where surgeons have to cope with soldiers evacuated way after the recommended time to save their limbs, also known as the ‘golden hour’.

This timeframe is the first 60 minutes after a traumatic injury when a tourniquet needs to be applied to a limb to prevent death from exsanguination.

According to a British instructor who trains Ukrainian soldiers, the harsh reality is this: ‘There is no longer a golden hour.’

Most foreign surgeons, especially the US ones, have never had to work in such harsh conditions, which makes Ukrainian surgeons’ experience a valuable lesson for Western war surgeons in case of a high-intensity conflict where the means are scarce and medical teams have to deal with the hand that was handed to them.

“When I talked to some US surgeons about how we deal with tourniquets, and what we do here, they couldn’t believe it,” Luher says. “They have a lot to learn from us, too.”

Drones from both sides make evacuation as difficult as attack maneuvers in sub-zero temperatures outside. When soldiers are wounded, some can take days before a ground drone can take them back into a safer zone.

For those heavily wounded who had to apply a tourniquet to stop the bleeding, time has become a death sentence. Tourniquets cut the blood flow to prevent massive blood loss, but it’s a double-edged sword.

When the blood flow stops, tissues begin to die, potentially causing necrosis or gangrene. After six hours or more, the amputation is more than certain, and removing the tourniquet too fast can lead to cardiac arrest as the blood suddenly coming back to the limb releases deadly toxins.

“We’ll slowly take this one first, and then this one,” orders “Tourist,” a young surgeon who, despite being in his 20s, has seen it all.

Ukraine doesn’t have the luxury of most US-fought wars, where wounded soldiers could be evacuated by helicopters. Instead, soldiers have to wait for days, if not weeks, before getting out, and more often than not, they’re being evacuated by ground drones to reach the first stabilization point.

Under the drone fire

Emergency services and medics are a target of choice for the Russian FPV pilots, who’ll do everything to finish off Ukrainian soldiers, even at their most vulnerable time.

Here, it looks like it’s gonna be a long night. It’s almost ten in the evening, and military paramedics have already dropped four wounded soldiers over the course of a few hours.

Most of the wounded are missing feet or legs, blown up by mines or by some FPV drones.

Drones are responsible for between 70 and 80% of those injured or killed on both sides of the war in Ukraine, according to a report published in January by a key Latvian intelligence service.

Yet, Tourist is used to it. He’s seen so many soldiers wounded that he felt the need to detach himself, otherwise he couldn’t keep a cool head at work.

Yet, he admits some circumstances are harder than others.

“I was in Kramatorsk when the Russians attacked the train station [in April 2022—ed],” he says. “I remember having to work on women, kids. Working on civilians is the hardest.”

Bloody Mozart

Despite the gruesome wounds and the flow of wounded soldiers, the atmosphere is calm and professional. Everyone knows their role, has their tasks assigned, and performs them in a ballet rehearsed a thousand times.

Every time, the protocol is the same: once the injured soldier is brought in, his clothes are removed and placed in a bag labelled with his name. This one’s leg is completely shredded, and the bone protrudes from the limb like some sort of burned stick.

Then begin the diagnostics: which wound should be treated first, an X-ray to determine where the bone is broken, and where to cut the limb to avoid the infection from spreading.

Here’s the dilemma: if the surgeons cut too high, they risk cutting healthy muscles that could help the trooper walk one day with the right prosthesis. The surgeons have no other choice but to check every bit of shredded muscle hanging from the bone with some electric device to carefully pick the cutting point.

While surgeons clean and operate, a speaker plays a carefully-picked playlist of Chopin and Mozart. Outside, from time to time, the blast of the artillery pierces the winter night.

“Here, it’s relatively safe, compared to the stabilization point,” says Luher, who’s been operating in different locations. “Back there, everything is flying, FPVs, gliding bomb, it’s way harder to work in these conditions.”

Inside the block, the potent, metallic smell of blood mingles with the powerful smell of iodine and tissues burned by the cauterizer machine.

One of the soldiers lying down is at risk of sepsis from a shrapnel trapped in his insides. The surgeon has no other choice but to open a wide hole in the abdomen and plunge his hand up to the wrist in the open guts to try and find it.

The constant bipping of the machinery strangely echoes Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 blasting from the speaker.

On the other operating table, the wound is clean, and the seesaw is ready. The fateful buzz starts. It only takes a few minutes to cut the bone clean. Then comes the hard part, re-sewing what’s left of healthy tissues around the leg, a delicate process that requires the full attention of the surgeons working on the limb as one.

Behind the masks, sweat pearls on the surgeons’ faces. Overall, the operation lasts two to three gruelling hours, but it’s a success, judging by the team's relief as they head out of the block, preceded by the unconscious soldier.

Meanwhile, Didenko, the soldier whose foot had been blown up by a butterfly mine, finally wakes up. The medical team miraculously saved his toes by reconstructing the skin over the exposed bones. He needs to get some proper rest and rehabilitation, but he’ll walk.

Didenko will live to see another day—a small victory for the team, until the next fight to save another life that’ll come through the corridor.

-42696701342093d1cdbc4069f0f07d6c.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)