- Category

- War in Ukraine

A New Landmine-Lined “Iron Curtain” Rises on NATO’s Border to Deter Russian Invasion

Six countries on NATO’s eastern flank, including Ukraine, are pulling out of the Ottawa Treaty and reintroducing landmines along 2,150 miles of border—what some are calling a new “Iron Curtain” against the growing threat of Russian invasion.

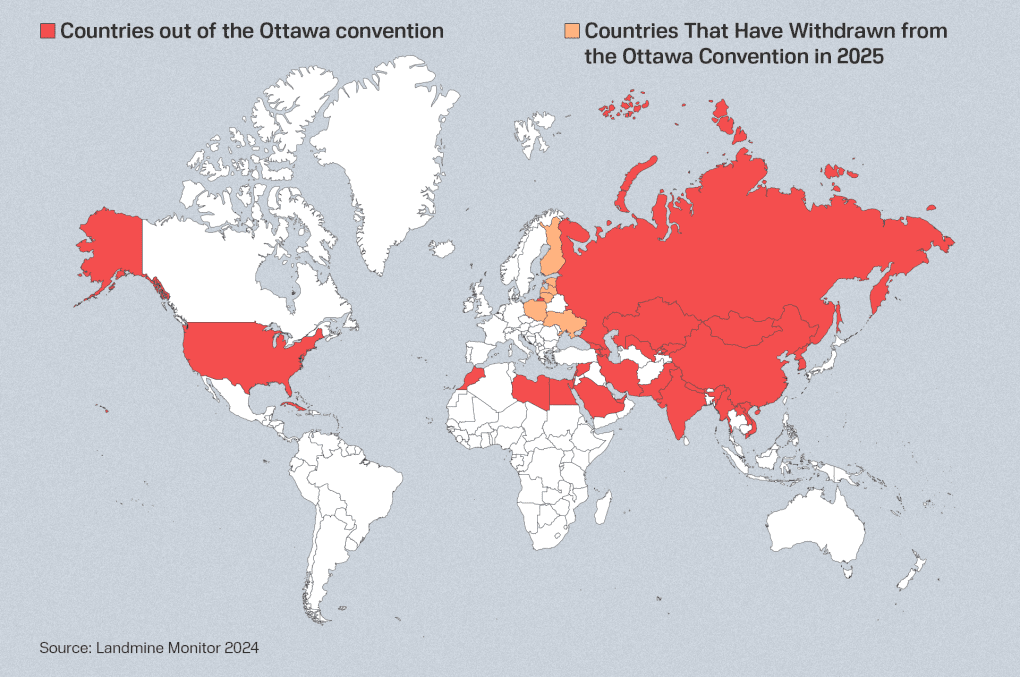

Recent news has seen six countries bordering Russia—Ukraine, Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—taking formal steps to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention and eventually form a new landmine “Iron Curtain” to protect their wooded, uninhabited borders from an eventual Russian invasion.

Why frontline NATO states are leaving now

The Ottawa Treaty, officially known as the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, entered into force in 1999. Since March 2025, 165 states have ratified or acceded to the treaty, which prohibits the use, stockpiling, production, and transfer of anti-personnel mines.

The moves, made between March and June 2025, come as regional governments cite an increasingly threatening security environment following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed a decree on June 29 initiating Ukraine’s formal withdrawal from the treaty. Parliament must confirm the decision before Ukraine can officially withdraw from the treaty.

Ukraine’s Foreign Affairs Ministry issued a statement citing the country’s compromised ability to defend itself under the treaty’s restrictions: “Ukraine has found itself in an unequal and unjust situation that restricts its right to self-defense as enshrined in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.” Article 1 of the treaty prohibits the use of anti-personnel mines under any circumstances.

How the Ottawa Treaty withdrawal changes NATO and global arms control

Poland completed its withdrawal process on June 26. The move was followed by a joint statement from the defense ministers of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, declaring, “With this decision, we are sending a clear message: our countries are prepared and can use every necessary measure to defend our security needs.”

Finland, which shares a 1,340-kilometer (832-mile) border with Russia, announced its intention to withdraw on April 1. Prime Minister Petteri Orpo explained the decision, stating, “To give [Finland] the possibility to prepare for the changes in the security environment in a more versatile way.”

In Vilnius, Lithuanian Defense Minister Dovilė Šakalienė defended the decision, calling Russia an “existential threat” to national sovereignty. Lithuania then announced plans to invest €800 million ($937 million) in the domestic production of landmines over the next several years.

Russia’s stockpiles defy global efforts to eliminate landmines

Jody Williams, a Nobel laureate and advocate for the ban on landmines, founded the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) in 1992. The organization grew to include 1,300 NGOs in 90 countries.

When governments refused to amend the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) in 1995, which included a protocol that addressed the use of antipersonnel landmines, booby traps, and other devices, Williams and the ICBL began a years-long effort to create a new one, the result being the Ottawa Treaty.

While the world ratified the treaty, Russia spoke out in November 2020, saying that it “shares the goals of the treaty and supports a world free of mines,” but views antipersonnel mines “as an effective way of ensuring the security of Russia’s borders,” refusing to ratify the treaty along with the United States, Israel, India, China and Iran (among others).

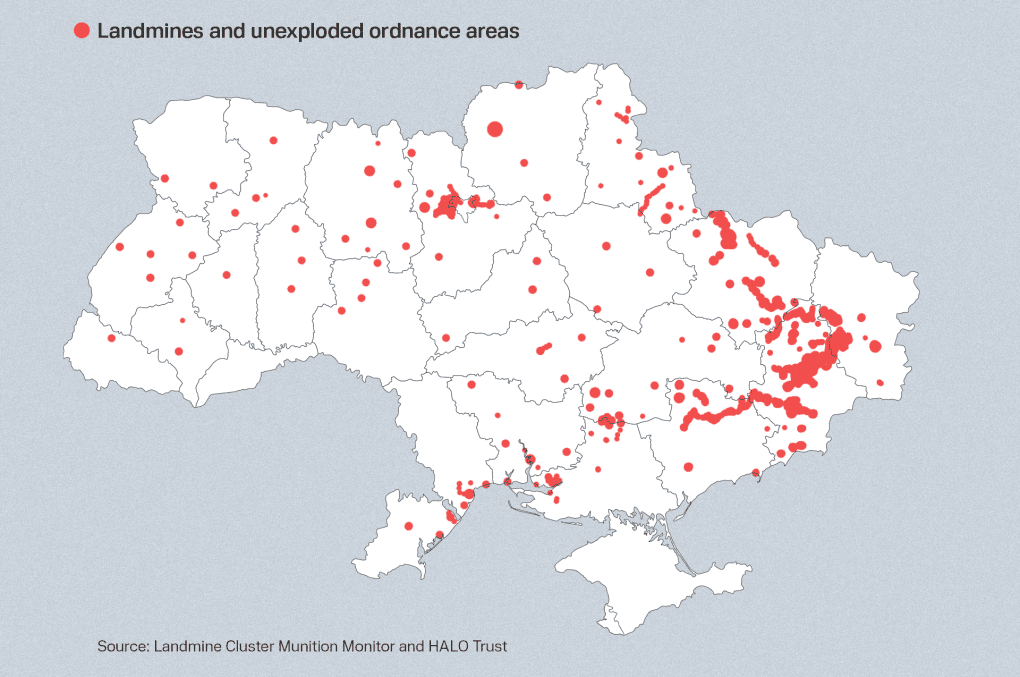

After Russia’s full-scale invasion, it’s estimated that up to 25 percent of Ukraine, equivalent to an area about twice the size of Austria, has been contaminated with landmines. Russia is effectively transforming Ukraine into the most mined country in the world.

For the signatories of the Ottawa treaty, the success of the campaign to ban landmines was palpable. In 1997, 25,000 people were killed or injured each year by landmines globally, but by 2013, that number had fallen to 3,300. The number of countries actively producing the weapons has reduced from dozens to just a handful.

In contrast, Russia’s Defense Minister, Sergei Ivanov, revealed in 2004 that the country stockpiled 26.5 million anti-personnel mines by 2024, many of which now kill and maim Ukrainians. Russian military units have also maintained landmine stocks in other countries, including 18,200 mines in Tajikistan, a signatory of the Mine Ban Treaty, the international civilian-led research initiative, Monitor reported.

What military planners say landmines offer

Zelenskyy justified Ukraine’s decision to leave the treaty in a nightly video address on June 28, saying Russia used mines with the “utmost cynicism” in Ukrainian territory. Then, he emphasized that anti-personnel mines are “often the instrument for which nothing can be substituted for defense purposes.”

The border between NATO states, Russia, and Belarus is largely sparsely populated and heavily forested, stretching over 3,500 kilometers (2,150 miles) from Finnish Lapland to Poland’s Lublin province.

This makes monitoring challenging amid rising concerns about a potential Russian attack on NATO territory.

NATO allies argue that, given the lack of resources—such as US artillery supplies or enough soldiers—mines provide a cost-effective solution, acting as a deterrent in a psychological battle, signaling to Russia that the borders are not passive.

UK newspaper The Telegraph’s chief foreign affairs commentator, David Blair, reported plans for a new “Iron Curtain” where millions of landmines would be deployed.

The states making up Europe’s border with Russia, in effect Europe’s first line of defense, “are in agreement,” said Francis Tusa, a UK defense journalist in The Independent. If Kyiv “loses its struggle against Russia, the latter may be emboldened to take military action against the Baltic states, Finland, or even Poland.”

Many defence specialists agree the timeline for this happening is “within three to five years”, making the need to prepare for a potential Russian invasion with all the tools available a priority for those in Russia’s line of fire.

Ukraine’s case as precedent

Ukraine now faces the dual challenge of defending its territory while managing the extensive costs of demining, both financially and in terms of lives lost. Since the full-scale war began, Russia has killed 13,300 Ukrainian civilians and injured more than 32,700.

“This is a step that the reality of war has long demanded,” said Ukrainian MP and Secretary of the Parliamentary Committee on National Security, Roman Kostenko, on Facebook. “Russia is not a party to this Convention and is massively using mines against our military and civilians. We cannot remain tied down in an environment where the enemy has no restrictions.”

In the latest development, Finland and Lithuania announced on July 9 that they are preparing to begin anti-personnel mine production in 2026. Poland, Latvia, and Estonia are likely to follow, and Ukraine is the likely recipient.

The reintroduction of anti-personnel mines along NATO’s 2,150-mile eastern frontier reflects a shift toward hardened deterrence, signaling a growing recognition within the EU that defending against Russian aggression demands credible, layered defenses—including measures once seen as obsolete. The return of landmines, despite their long-term danger, underscores how real the Russian threat is—not only to Ukraine, but to all of Europe.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)