- Category

- War in Ukraine

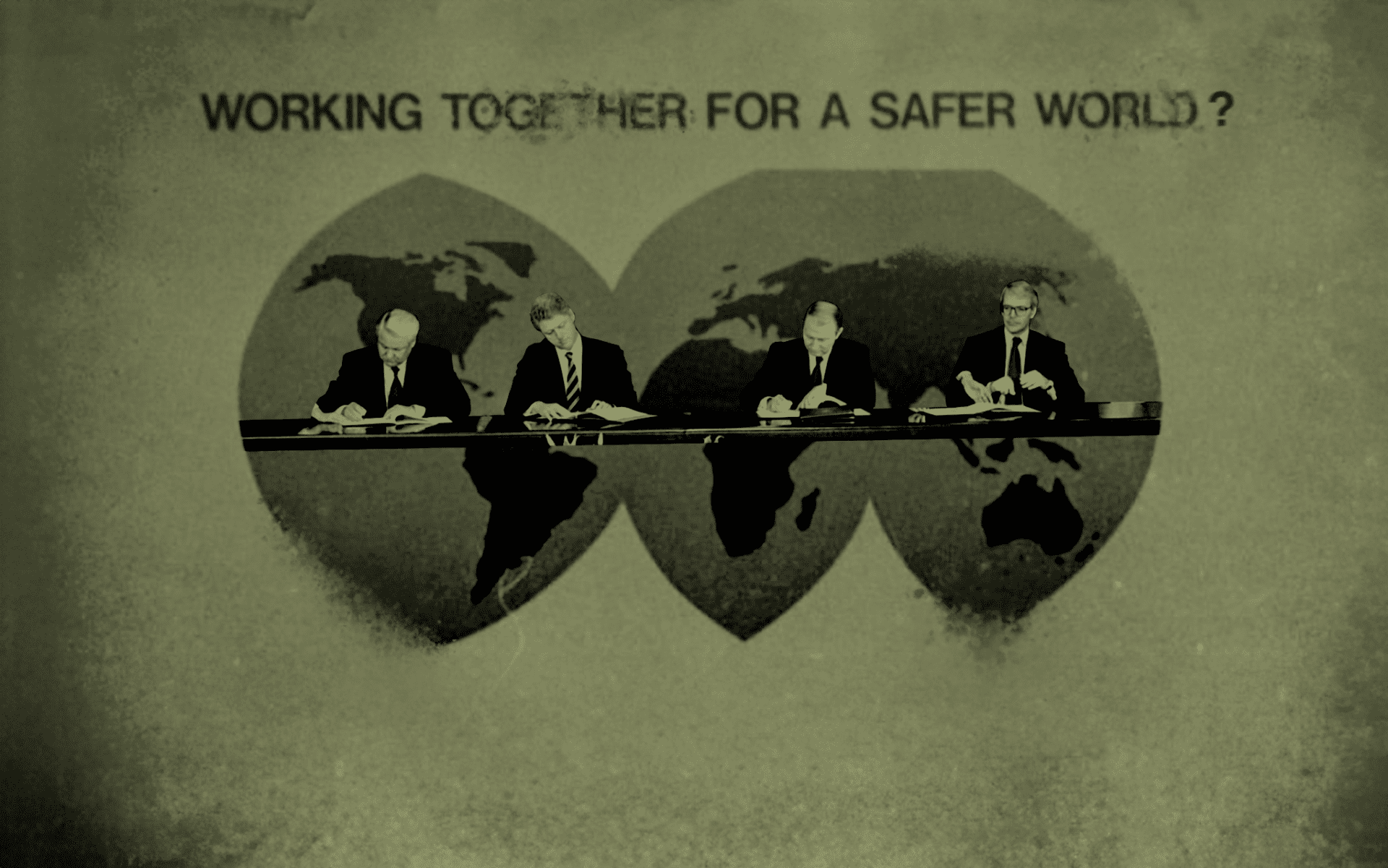

A Timeline of How Ukraine Gave Up Its Nuclear Arsenal for Peace and Got Russia’s War Instead

Imagine inheriting the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal, only to have to give it all away. This is what happened to Ukraine, and now everyone is paying the price. Here’s how a deal intended to ensure peace unraveled into war.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991, newly independent Ukraine inherited a formidable nuclear arsenal. By that time, the USSR had stationed some 1,900 nuclear warheads, 176 intercontinental ballistic missiles stored in underground launch silos, and 44 strategic bombers on the territory of Ukraine. In addition to intercontinental ballistic missiles, Ukraine also had tactical nuclear weapons—up to 4,000 nuclear warheads on ground-to-ground or air-to-ground missiles. Ukraine’s arsenal was the third largest in the world. Only the Soviet Union and the US possessed more nuclear arms.

In 1994, however, Ukraine signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as a non-nuclear weapon state-party and by 1996 had transferred all of its nuclear warheads to Russia. The last strategic nuclear delivery vehicle in Ukraine was dismantled in 2001 under the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

Ukraine’s relinquishment of its nuclear arsenal has often been acclaimed as a success story in nuclear arms control. But even at that time, both Ukrainian and US experts expressed doubt as to whether denuclearization was a good decision, arguing that Ukraine’s nuclear weapons provided its only reliable deterrent against potential Russian aggression.

And while the Budapest Memorandum was presented to Ukraine as a cornerstone for its security, its ultimate failure to protect Ukraine’s sovereignty became evident over time.

On the path to a “New Europe”

After regaining independence, Ukraine’s international partners, who sought to limit nuclear proliferation globally, were reluctant to have dealings with Ukraine as a nuclear power. From the outset of its independence, Ukraine was favorably disposed to gain broader diplomatic support by signing the NPT, under which non-nuclear-weapon state-parties obliged to commit to not manufacturing or acquiring nuclear weapons.

This was part of its effort to earn global acknowledgement as a sovereign, independent nation. In the 1990 Declaration of State Sovereignty, a document decreeing that the laws of the Ukrainian SSR took precedence over those of the USSR, Ukraine pledged “not to accept, produce, or acquire nuclear weapons.” This commitment was reaffirmed in the 1991 statement of the Parliament of Ukraine on the non-nuclear weapon status of Ukraine.

Yet Ukraine’s total nuclear disarmament would not be easy. Half a decade of extensive diplomatic negotiations and internal political strife would be required to remove all nuclear weapons and related equipment from the country’s territory. The first phase of disarmament was governed by the 1992 Lisbon Protocol.

The Lisbon Protocol

Ukraine signed the Lisbon Protocol on May 23, 1992. The protocol obliged Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine to deliver the nuclear weapons stationed on their territory to Russia. It also required that the three countries become parties to START and the NPT.

By the end of the year, however, pro-nuclear sentiment began to rise within the Ukrainian parliament. Some members advocated for temporary nuclear status, while others held that the country should claim ownership and seize operational control of the warheads.

In April 1993, 162 Ukrainian politicians signed a statement detailing 13 further preconditions for the ratification of START. These included security assurances from Russia and the US, as well as financial aid for the dismantlement of weapons and compensation for the commercial value of the uranium in the weapons.

The following month, the US offered additional financial assistance to incentivize Ukraine’s ratification of START. This prompted further negotiations between Ukraine, Russia, and the US on the terms of nuclear disarmament. During these negotiations, Kyiv remained resolute in demanding solid security guarantees as an indispensable prerequisite for denuclearization. The US and Russia complied, and would formalize these commitments in the Budapest Memorandum.

The Budapest Memorandum

The US, Russia and the UK signed the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurance on December 5, 1994. The signatories pledged to respect the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence of Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, and not to use or threaten to use force against these states.

The same day the memorandum was signed, Ukraine acceded to the NPT as a non-nuclear weapon state, and fulfilled the final conditions for START ratification.

On December 4, 2009, Russia and the United States issued a joint statement confirming that the security assurances outlined in the Budapest Memorandum would remain valid after the expiration of START in 2009.

The Budapest Memorandum’s failure became apparent when its security guarantees were ignored, particularly in light of Russia’s future actions. The agreement did not foresee a scenario where Russia, under an revanchist, expansionist leader like Vladimir Putin, could so blatantly disregard its obligations and international law.

Many believe that Ukraine’s decision to relinquish its nuclear weapons was influenced by external pressures, rather than being an entirely unilateral decision. Political and material considerations, including the NPT, led Ukraine–along with Belarus, Kazakhstan, and the Baltic States–to completely relinquish its nuclear arsenal. The result was that, from 1994 to 1998, only five countries officially had nuclear weapons: United States, Russia, United Kingdom, France, and China. India and Pakistan joined the group in 1998, raising the number of countries with acknowledged nuclear weapons programs to seven.

“Hand over your gun, and we promise you’ll be safe!”

Ukraine gave up its nuclear arsenal in exchange for economic support and what were meant to be ironclad security assurances respecting its sovereignty and territorial integrity. However, on February 20, 2014, in flagrant violation of the Budapest Memorandum, Russia invaded Ukraine through Crimea and across its eastern border, occupying the peninsula and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. This marked the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine, which escalated into a full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022.

Ultimately, the Budapest Memorandum failed to guarantee Ukraine’s security.

Russia has consistently used its nuclear arsenal–which currently possesses the largest nuclear stockpile on the planet, currently making up approximately 5,580 nuclear warheads as of 2024–as a tool of intimidation and blackmail against Ukraine and the West. Compounding the threat, Ukraine’s largest nuclear power station, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, has been under Russian occupation for over two years. The Russian military has interfered with the safe management of the plant, including by placing explosives and military equipment on-site, risking a catastrophic nuclear accident.

The attempted annexation of Crimea and the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion have sparked increasing calls for Ukraine’s nuclear rearmament, with many arguing that the country is both legally and morally entitled to restore its nuclear status. The war in Ukraine has revealed not the merits of arms control, but the vulnerabilities and risks of nuclear disarmament—raising concerns that other potential nuclear powers may reconsider their own disarmament strategies. Ultimately, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights the risks of nuclear disarmament when security guarantees are hollow and easily disregarded.

In response, Ukraine’s Victory Plan calls for the deployment of a robust non-nuclear deterrence package, aimed not only at shielding Ukraine from further Russian aggression but also at limiting Russia’s military capabilities—a threat that now extends beyond Europe and NATO to the entire globe. The stakes are higher than ever: without decisive action, the cost of inaction may be felt far beyond Ukraine’s borders.

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)