- Category

- War in Ukraine

Inside Ukraine's Nuclear Command Center That Faded Into History

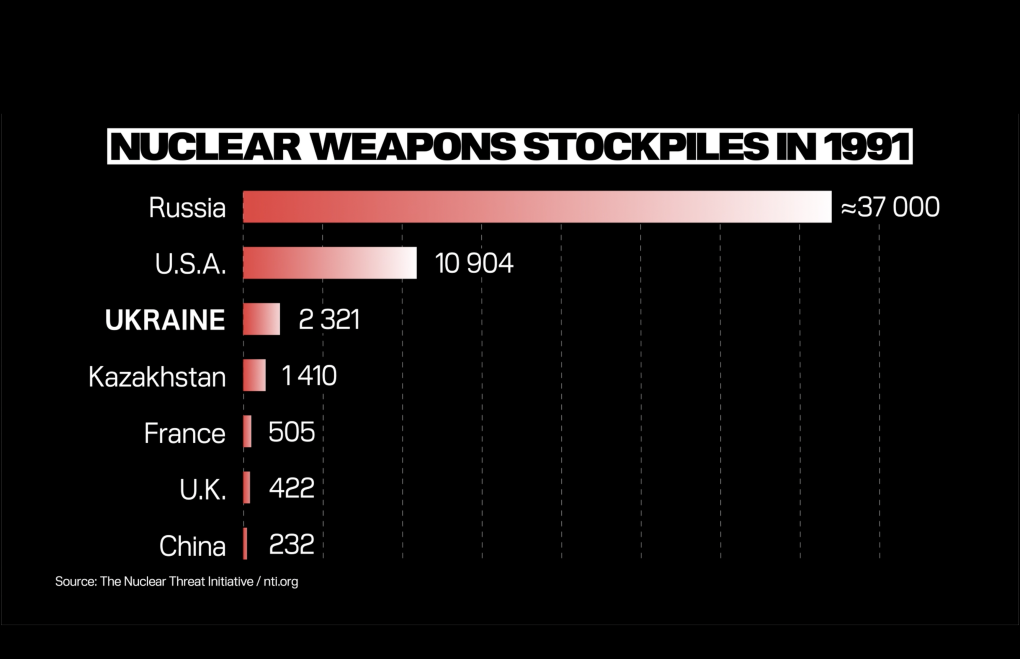

In 1991, an independent Ukraine signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances in 1994. These decisions, often questioned by Ukrainians today, led Ukraine to eliminate the world's third-largest nuclear arsenal.

What remained of the once formidable arsenal? Join us as we explore this period in Ukraine's history, visiting a decommissioned missile base—a former missile silo and command post—in Ukraine’s south that once managed strategic nuclear launches.

Our guide is Oleksandr, an ex-serviceman of the 43rd Missile Army, who offers insights into the complexities of nuclear disarmament of Ukraine.

This museum is almost all that remains of Ukraine's once third-most powerful nuclear potential.

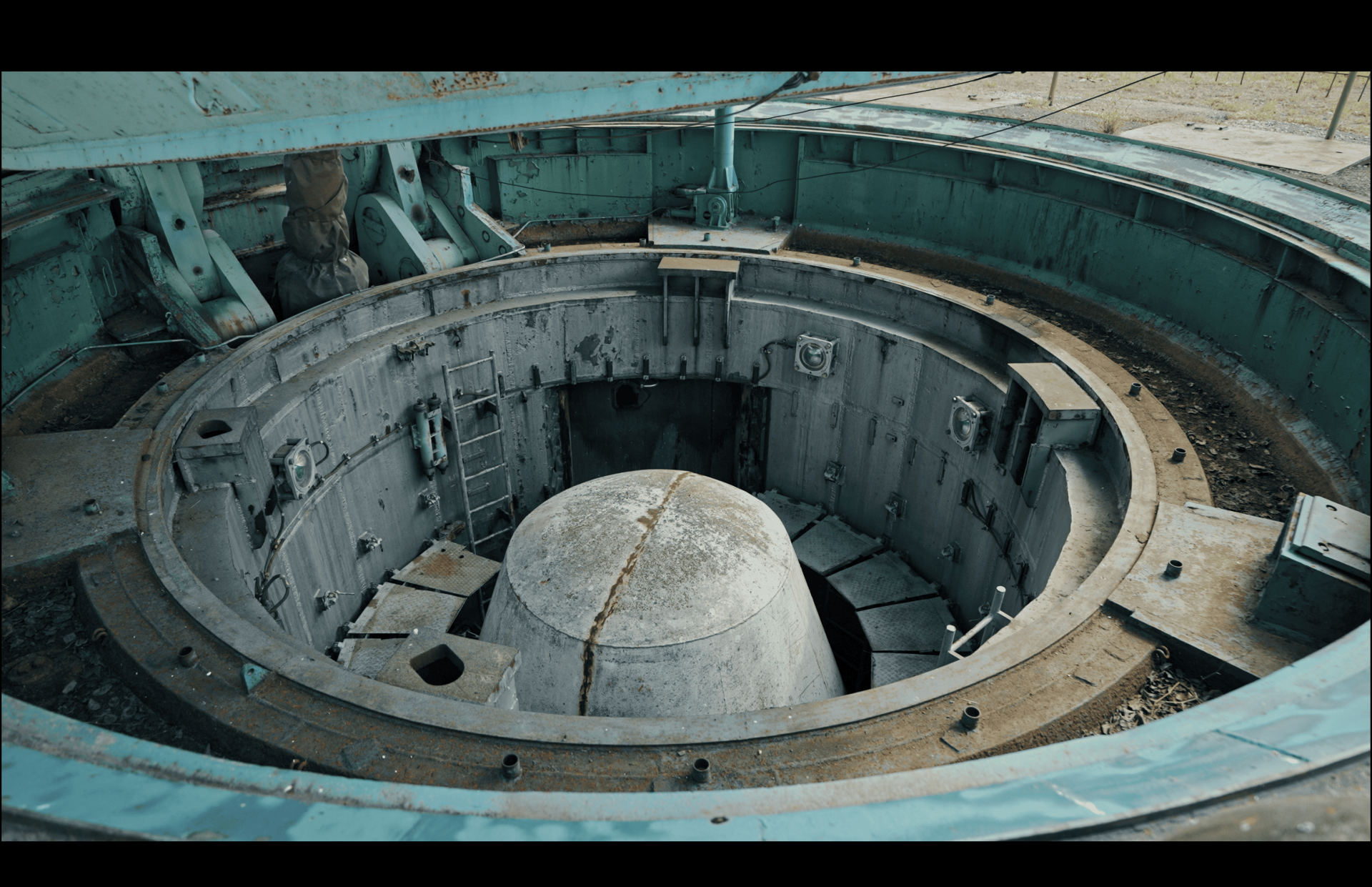

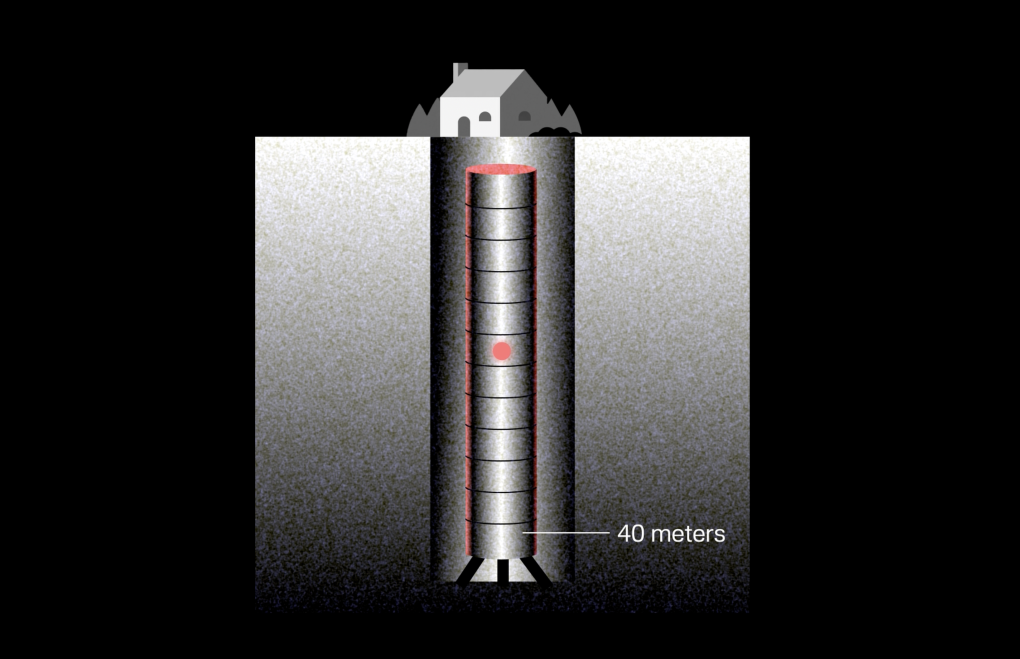

What did the nuclear missile silos look like?

Each silo had a 121-ton protective device and an iron lid covering the shaft. The shaft was 38 meters deep and lined with 3 to 7-centimeter-thick metal. Below the shaft was an apparatus chamber surrounded by 2 meters of reinforced concrete. The missile was placed inside a transport-and-launch container at the bottom of the shaft. If it was for combat use, the lid opened in eight seconds, the powder pressure accumulator under the missile was activated, and then the missile was pushed out, igniting its engines as it took off into the air.

What kind of missiles did Ukraine have?

Ukraine’s missiles were produced at Pivdenmash, a missile plant located in Dnipro, Ukraine. Pivdenmash produced the majority of the missiles that were in service with Ukraine's Missile Forces, like SS-24 missiles, powered by solid fuel.

The largest missile that was in service in the Soviet army was the SS-18, called "Voevoda" by the Soviets and "Satan" by the Americans. It was 34 meters and 30 centimeters long, and 3 meters wide. The launch weight was 211 tons, and its range was up to 16,000 kilometers, meaning that it could reach any target on the globe. Although these missiles were produced in Ukraine, they were not in service in Ukraine. These missiles were only present on the territory of Russia, and two divisions were in Kazakhstan.

Although some SS-18s remain in Russia’s inventory, they haven’t been maintained by Ukrainian specialists for years. Russia is now decommissioning these missiles, replacing them with new Sarmat missiles, modeled on the SS-18.

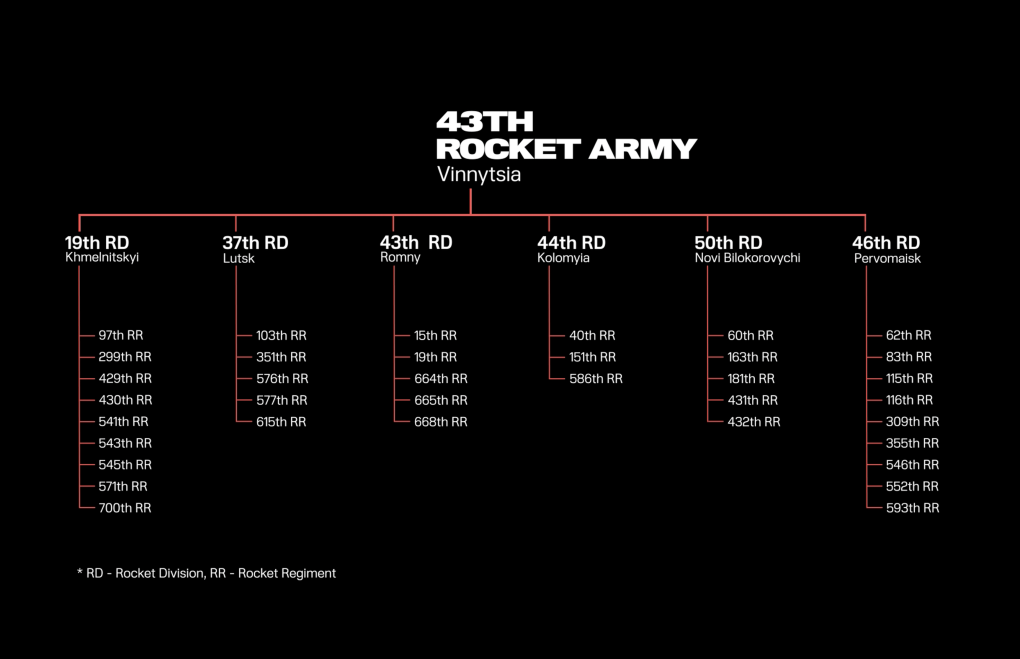

Where were Ukraine's nuclear missiles located?

Ukraine housed six missile divisions on its territory: Pervomaisk, Khmelnytskyi, Kolomyia, Lutsk, Novi Bilokorovychi, and Romny. They were all unified into one Missile Army, headquartered in the city of Vinnytsia. It was the 43rd Missile Army and the most powerful missile formation in the Soviet Union. Khmelnytskyi and Pervomaisk divisions stored the missiles underground, concealing them. Other divisions were armed with missile launcher vehicles. By 1993, only two missile divisions were left: Khmelnytskyi and Pervomaisk, and they had 176 missile silos. Even with just these two divisions, Ukraine ranked third in the world in terms of the number of nuclear weapons.

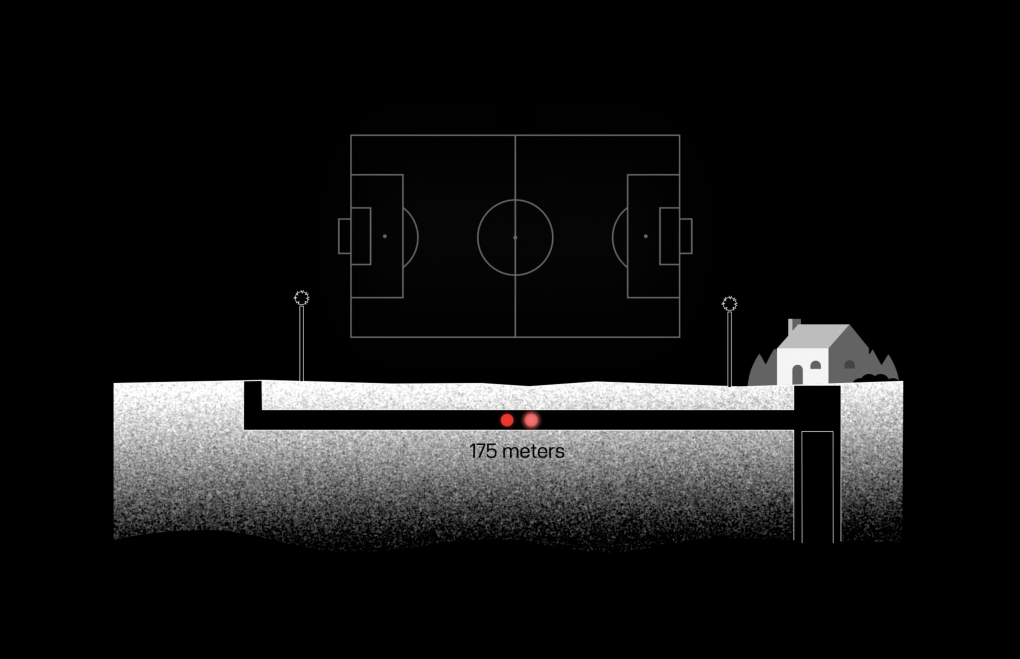

How did the missile silos work?

The underground passages were located at a depth of 2 to 3 meters underground, with the first one 175 meters long. Above ground, there were alarm sensors, minefields, and a powered grid that was constantly under voltage. To keep these means of protection activated at all times and to remain undetected, the officers used the underground passages to reach the command post.

“We reach the entrance to the underground command center,” says Oleksandr.

“Here, you can see the first security doors, which weigh almost one ton and are made of reinforced concrete. They open automatically with the help of hydraulics.”

To open the door, the officer had to know two passwords. The first was verbal, usually, the name of a city followed by a number. He would say the password using the phone, and if it was correct, the officers on the other end would supply power to the console. Then he had to type in the second password, a certain combination of numbers.

The officers would then descend 45 meters down into the shaft using a walk-through elevator. The eleventh floor is the most secret facility of the Strategic Missile Forces. This facility had the capability to launch ten intercontinental ballistic missiles.

How did the launch sequence work?

The launch process involved a complex sequence of steps, culminating in the launch command.

“Combat mode! Flight plan entered! Start of launch sequence! Launch sequence received, entering code. Attention! Account, launch key! Attention, account, fire!”

A pause. The alarm signal’s blaring. The missile flies into the air.

“Launch number one has been completed.”

Then the officer picks up the phone.

“Sir, launches 1 to 7 have been completed successfully!”

After the launch, the command post would brace for impact, as enemy missiles would likely target their location. The command center was equipped with special seats similar to those in airplanes, and a four-point seat belt system to secure personnel during a potential nuclear impact. The officers would then lower the armrests and wait in this position for the impact. If the command post shook, the crew shook with it.

Having survived, the crew was then to pull out an ashtray with shaking hands and smoke. Cigarettes and lighters were confiscated when entering the command post, but surviving a nuclear explosion had its perks—an emergency box with necessities, including a couple of packs of cigarettes for smokers to relieve the tension afterward.

How was the command post protected?

The command post was designed to withstand the effects of a nuclear explosion. Built deep underground, it was equipped with 28 large hydraulic shock absorbers to counteract vibrations from an earthquake, which would likely accompany a nuclear blast. The container housing the command post could move within the shaft, both vertically and horizontally, to further absorb shocks. This design ensured that equipment and personnel could continue to function after an explosion.

At any given time, six people were present—three resting and three on duty. Shifts changed every six hours. During peacetime, personnel spent six hours in the command post before moving to a designated resting area. However, in the event of a nuclear explosion, leaving the post would be impossible, and the command center would switch to full autonomy.

It had water and food for six people, two diesel power plants, and 120 batteries for electricity. Regeneration tables were in place to absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, similar to systems used in submarines. These measures were designed to sustain six officers for 45 days in full autonomy.

What happened to the nuclear weapons in Ukraine after independence?

There were 176 intercontinental ballistic nuclear missiles and an equal number of launch silos in Ukraine, located in various regions.

After gaining independence, Ukraine pledged to become a non-nuclear weapon state, agreeing not to produce, use, or store nuclear weapons. All nuclear weapons on its territory were required to be dismantled. The process began with the removal of mobile missile launchers, followed by the decommissioning of silo launchers starting in 1995.

The decommissioning process involved draining liquid fuel, carefully removing the missiles and transporting them by rail to a facility in Pavlohrad for destruction. The silo launchers were partially demolished with explosives, and the remaining metal structures were manually dismantled using specialized equipment. The areas were then backfilled with dirt, capped with concrete, and covered with fertile soil.

All of the missile silos, except one, were destroyed, making their restoration impossible.

Why did Ukraine relinquish its nuclear arsenal?

“Maintaining a nuclear arsenal was expensive,” says Oleksandr.

“The mistake was giving up our nuclear status entirely. In addition to intercontinental ballistic missiles, Ukraine also had tactical nuclear weapons—up to 4,000 nuclear warheads on ground-to-ground or air-to-ground missiles”

These missiles, including the Tochka-U, the KH-22, and the KH-55 missile, had limited ranges. Ukraine could have maintained some of its nuclear arsenal by keeping a few dozen nuclear warheads for tactical missiles while giving up strategic weapons.

“This would have served as a deterrent against attacks,” said the ex-serviceman.

However, political and material considerations, including the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, led Ukraine to relinquish its nuclear arsenal completely, alongside Belarus, Kazakhstan, and the Baltic States. Only five countries had nuclear weapons: the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France, and China. India and Pakistan later joined this group, bringing the total to seven countries with nuclear weapons.

And now, all that remains is former nuclear facilities.

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)