- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Ukraine Started 2026 with Record Anti-Shahed Drone Production and a New Era in Air Defense

Self-reliance has become the defining narrative for Ukraine’s sprouting defense industry. Foreign military aid played a key role in Ukraine’s early successes, but years of dependence on this aid exposed huge gaps in that framework, especially when coupled with stagnation in political will and slow bureaucratic processes.

For a country under constant attack, air defense is critical—especially as Russia continues a sustained campaign against Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Power plants and transmission systems are hit repeatedly, often with drones and missiles that cost a fraction of the mostly NATO-made interceptor systems used to stop them.

Even with strong international support, supply cannot always keep pace with this scale. That imbalance forced Ukraine to adapt. Over the past year, it ramped up domestic production and integrated a record number of cheap, scalable FPV interceptor drones into its multi-layered air-defense architecture, specifically designed to protect the country against mass drone attacks.

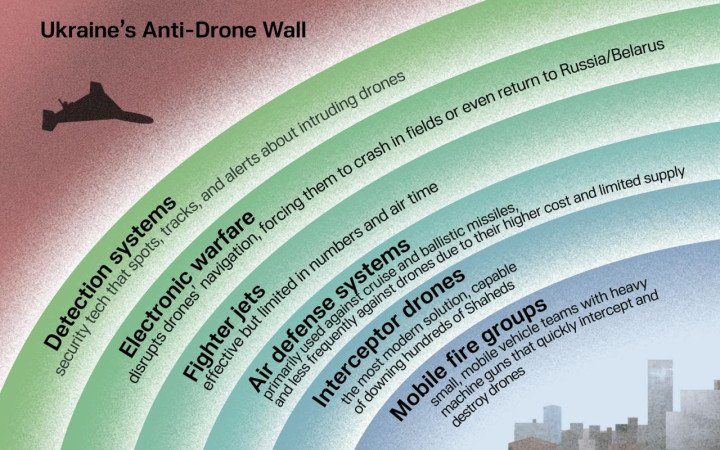

The core of Ukraine’s air defense architecture

The most consequential development of 2024–2025 was Ukraine’s decision to treat interceptor drones as a primary capability rather than an experiment. After President Zelenskyy set the target in July, Ukraine had, as of January 7, 2026, ramped up production to 1,500 FPV-based interceptor drones a day, designed specifically to counter Shahed-type threats and other low-cost aerial targets.

Russia’s ability to launch hundreds or thousands of drones over short periods makes missile-only interception economically unsustainable. Ukrainian interceptor drones are meant to absorb volume. They do not replace missile systems; they preserve them. By matching cheap threats with cheap counters, Ukraine began reshaping the cost curve of air defense rather than trying to outrun it.

By the end of 2025, interceptor drones, ranging from $3,000 to $5,000, had been integrated at scale into various air defense units and achieved surprising results. According to President Zelenskyy, the average success rate of these drones is 68%. The Russian Shahed drone can cost upwards of $100,000—still much cheaper than any missile.

This places Ukraine ahead of all European countries that are currently exploring similar ideas under the EU’s “Drone Wall” framework. Several European states—particularly along NATO’s eastern flank—have already experienced Russian drones violating their airspace, prompting a coordinated response.

According to Luke Pollard, the UK’s Minister of Defense and Industry, the country aims to produce 2,000 interceptor drones a month to hand over to Ukraine under the joint UK-Ukraine project dubbed “Octopus”.

Scaling production

Interceptor drones required a different approach to production. Early in the war, FPVs were built primarily for strike missions, often assembled ad hoc and customized at the unit level. That model does not work for air defense. Interception demands reliability, predictable performance, and rapid replacement.

Over the past year, Ukraine standardized FPV interceptor production around interception-specific requirements. Frames, propulsion systems, optics, and guidance were optimized for speed, climb rate, and terminal accuracy rather than payload delivery. This reduced failure rates and simplified maintenance, allowing units to plan air-defense coverage instead of improvising it.

This shift also changed how Ukrainian drones are used more broadly. Reconnaissance UAVs increasingly support interceptor operations by extending detection and tracking beyond radar coverage. Data from visual observers, acoustic sensors, and UAV feeds is used to cue interceptor launches within minutes. Ukrainian drone operators trained for interception now work as part of distributed air defense teams rather than isolated FPV crews.

Other drone categories increasingly play supporting roles. Ukrainian long-range drones pressure launch infrastructure and logistics deeper inside Russia, indirectly reducing attack volumes. Ukrainian naval drones constrain platforms used to support aerial attacks from the Black Sea. But these systems are secondary to the central task: keeping air-defense saturation manageable.

Detection, targeting, and the sensor layer

At the top of Ukraine’s layered air defense are missile interceptors. Sophisticated systems like Patriot, NASAMS, IRIS-T, and SAMP/T intercept ballistic and high-speed cruise missiles. They protect major cities, airfields, and energy infrastructure, but they are expensive and finite. Using them against every low-cost drone would risk exhausting stockpiles in a single large-scale attack.

Below that sits the detection layer. Ukraine relies on a mix of military radar, mobile sensors, acoustic detection, and visual observation. Civilian monitoring has become part of this ecosystem. Telegram channels alert civilians in real time to where the threat is, where it's heading, and how many are in the sky.

Gepard self-propelled anti-aircraft guns below—semi-automated, radar-guided, and highly effective against Shaheds and cruise missiles, especially when cued by external detection rather than relying solely on onboard sensors.

Mobile fire groups form the next line. Armed with machine guns, MANPADS, and electronic-warfare tools, these teams are highly mobile and effectively reduce the volume of drones before they can enter populated areas.

Interceptor drones fill the gap between missiles and guns. Some Russian drones operate at altitudes of up to five kilometers, placing them beyond the effective range of Gepards and mobile fire teams, while not always justifying the use of expensive missile interceptors. The potential of drone interceptors is only now becoming clear outside of testing environments and in real operational conditions.

Training, software, and the human element

Ukraine has had to create a new type of Ukrainian drone operator: part FPV pilot, part air-defense crew. Interception is fundamentally different from strike missions. Operators track moving aerial targets, manage closure speed and altitude, and make decisions under extreme time pressure, often at night. As interceptor drones scaled, so did dedicated training. Reports describe the emergence of specialized teams and training centers built around specific interceptor platforms. Coverage by Militarnyi noted that the STING interceptor drone moved into mass production alongside a structured operator-training pipeline.

FPV interceptor drone vs. russian Shahed

— Defense of Ukraine (@DefenceU) December 23, 2025

Interceptor drones are becoming a vital part of modern air defense, protecting our people from russian terror.

📹: @DI_Ukraine pic.twitter.com/wjIi8z3GMn

On the software side, the direction is clear even where public details remain limited. UNITED24 Media has reported on an AI-enabled “drone wall” concept, known as DWS-1, built around FPV-type interceptors coordinated through a centralized command system. The idea—still under development—is to allow a small number of operators to manage large numbers of interceptor drones, reducing dependence on clean GPS and uninterrupted communications. It is not a baseline today, but it shows where Ukraine is pushing: fewer operators, tighter coordination, and greater resilience under electronic warfare.

Ukraine publishes regular air-defense statistics, but it rarely breaks down how many Shaheds are downed by interceptor drones versus missiles, guns, or electronic warfare. What is clear is the scale of pressure.

For interceptor drones, the most credible evidence comes from documented kills. Developers of the 3D-printed Salyut interceptor have released video footage showing the most recent successful shoot-downs of Shahed-type drones during live attacks.

This is why Europe is paying attention. “Drone Wall” discussions are not symbolic; they reflect a shared vulnerability as Russian drones increasingly test European airspace. The difference is tempo. Ukraine is engaged in a sustained, high-volume air campaign targeting its energy infrastructure. Its response has been to make interception scalable enough to survive that pressure. As Reuters put it, interceptor drones help conserve expensive missiles for cruise and ballistic threats while expanding capacity against mass drone attacks.

By 2025, Ukraine's drone production reached record levels. But the significance lies less in output than in intent. Ukrainian drones are now built around interception as a strategic priority. That shift reflects a broader lesson of the war: modern air defense is no longer defined by single systems, but by how well a country can adapt its economics, training, and technology to sustained pressure.

Cover illustration is of a Ukrainian interceptor drone (Image: DOT / Ministry of Defense UA)

-ee9506acb4a74005a41b4b58a1fc4910.webp)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)