- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Ukraine Secured Passage for Grain in the Black Sea, and How Russia Keeps Threatening It

After Ukraine managed to stop the dominance of the Russian fleet in the Black Sea in 2023, maritime exports nearly doubled. The vast majority of exports are agricultural products, which are part of global food security and go to countries in need. But what is Russia doing during this time? Bombing Ukrainian ports.

The Black Sea is the main channel for exporting Ukrainian raw materials and goods. In 2021, 154 million tons of cargo were exported through it—a record high number. In recent years, port infrastructure began to recover, with investors from the Middle East and local entrepreneurs coming in. One of the key export resources is grain and agricultural products, as Ukraine is among the top five global food suppliers.

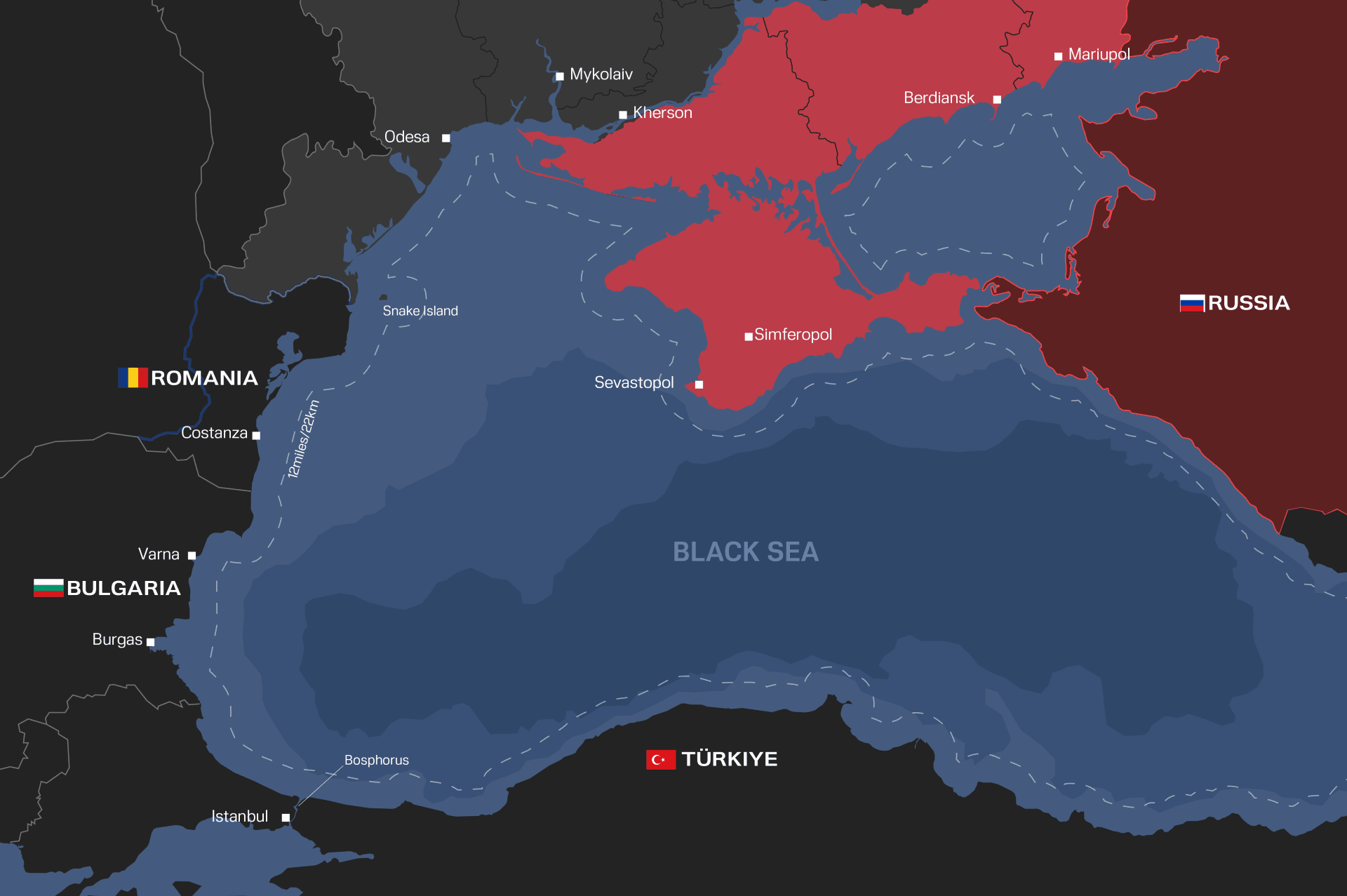

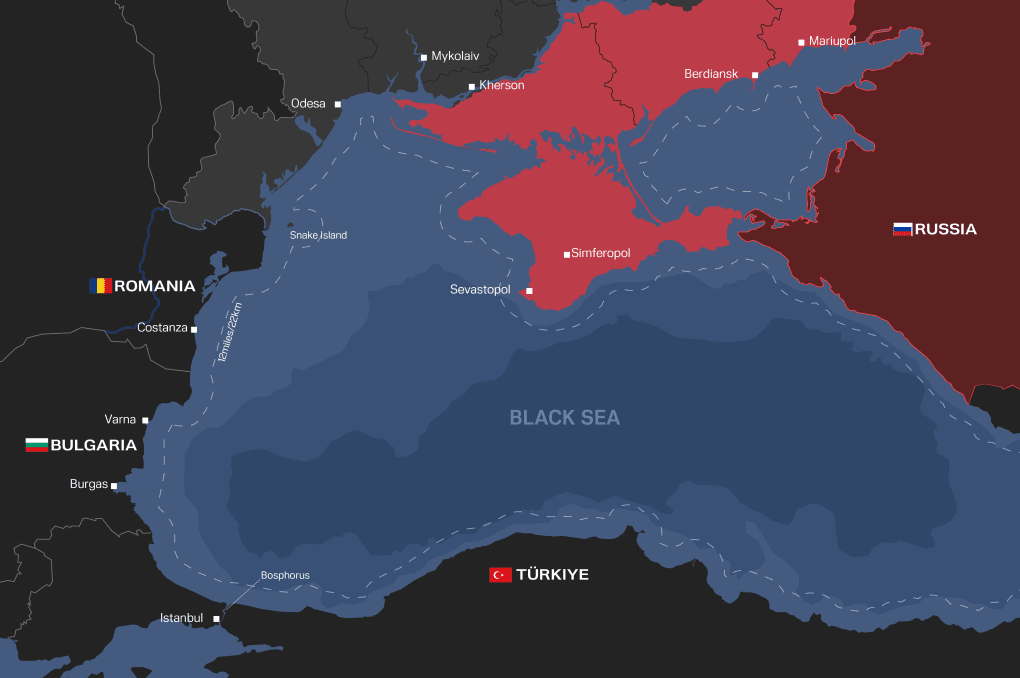

But the full-scale invasion changed everything. Russia took control of the Black Sea, seized some ports, and began shelling others. It was also preparing an amphibious landing operation in Odesa. This blocked exports. For Ukraine, and for the global market, this was a major blow: food prices began to rise.

To bring Ukraine back to the global market, the so-called Black Sea Grain Initiative was created. It consisted of two separate agreements: one between the UN, Türkiye, and Ukraine, and another between the UN, Türkiye, and Russia. Ships carrying grain and other crops had to pass additional inspections in Turkish ports with Russian participation. The deal was signed in July 2022.

In the following four months, Ukraine exported 9.5 million tons of cargo. But within six months, monthly exports fell to under 2 million tons. The constant delays of Russian inspections took a toll—sometimes only 1–2 ships were cleared per day, and sometimes none at all. For comparison, during the first months of the corridor's operation, 400 ships passed through successfully. By summer 2023, it became clear: the deal had run its course.

Ukraine, critically dependent on exports, understood that a fair agreement with Russia was impossible. The rules of the game had to change.

Ukraine’s maritime corridor

The Grain Initiative had two problems. First, low export volumes and unpredictable inspection procedures, which meant that grain could go bad in ports or once it was aboard ships. Second, the export was limited only to food. For Ukraine, it was critical to restore the ability to export all types of civilian cargo: ore, metals, and other products.

To organize its own corridor, Ukraine had to work on several fronts simultaneously.

Liberation of Snake Island

Snake Island lies 38 km from Ukrainian territory and 120 km from Odesa. Russia captured it in February 2022, turning it into a base to control the Ukrainian coast and sea routes. Over the next four months, Ukraine launched several successful attacks, driving Russian forces off the island and reducing their surveillance and strike capabilities.

Liberation of the right bank of Kherson

A major threat came from the large Russian group that captured Kherson in the early days of the invasion, crossed to the right bank of the Dnipro, and began advancing toward Mykolaiv. Ukraine’s successful defense prevented the breakthrough and a possible offensive on Odesa. By the end of 2022, the Ukrainian Armed Forces had pushed Russian troops out of Kherson, liberating the city. This also weakened Russia’s ability to control parts of Ukraine’s sea area.

Military operations

Pushing Russian ships away from Odesa’s ports was achieved with the help of allies. Ukraine had stocks of its own Neptune anti-ship missiles, and partners supplied Harpoon missiles—each capable of flying up to 300 km, depending on the version.

Long-range Storm Shadow / SCALP missiles enabled strikes on Russian Black Sea Fleet ships directly in Crimea. Before this, Ukraine independently destroyed the fleet’s flagship—the cruiser Moskva. These long-range strikes also sank a submarine and several more warships.

Unmanned sea drones were the real game changers. Costing a few hundred thousand dollars each, they managed to destroy or damage multiple Russian naval vessels.

Even more important than the destruction itself was the threat they posed: the Black Sea was no longer safe for Russia. To protect its ships, Russia had to move some of them to ports within its territory and hide others in Crimean ports. Going out to sea was no longer safe—and it still isn’t. Modified sea drones are now armed with anti-aircraft missiles and serve as platforms for UAVs. One operation even destroyed two helicopters and enemy ground equipment.

Restoring port operations

Thanks to all these efforts, in the summer of 2023 Ukraine secured a 22-kilometer zone of territorial waters. Ships left Ukrainian ports and entered the territorial waters of Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey. Heavier-tonnage vessels that needed deeper waters could travel beyond this line—and they also received protection, although Ukraine doesn’t disclose security details due to risks.

Ukraine’s exports gradually resumed. By autumn 2023, the country exported 8.6 million tons of cargo—2 million of which were non-food items. For the first time since the full-scale invasion, non-agricultural goods were exported by sea. In February 2024 alone, Ukraine exported 8 million tons of various cargo types.

By the end of 2024, Ukraine reached impressive transshipment figures—just under 100 million tons, compared to 60 million in 2023. For comparison, the Black Sea Grain Initiative resulted in 33 million tons of food exports over one year. Last year, 9,061 vessels passed through the corridor—4,651 arriving in Ukraine, and 4,410 departing for other ports.

Russia’s response? Bombings. Right after Ukraine exited the Grain Initiative, Russia began bombarding Ukrainian ports. On July 19, 20, 21, and 23, it targeted Odesa’s port infrastructure, grain warehouses, and the city itself. Starting July 24, Russia also shelled the Danube ports in the Odesa region for several days.

By the end of autumn 2023, Russia had launched dozens of attacks: damaging 300 port infrastructure facilities, 177 vehicles, and 22 civilian vessels.

The shelling hasn’t stopped. One of the recent incidents happened in March 2025, when Russia struck port infrastructure. The attack killed four Syrians and injured two more. At the time, they were loading wheat onto a ship bound for Algeria.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)