- Category

- War in Ukraine

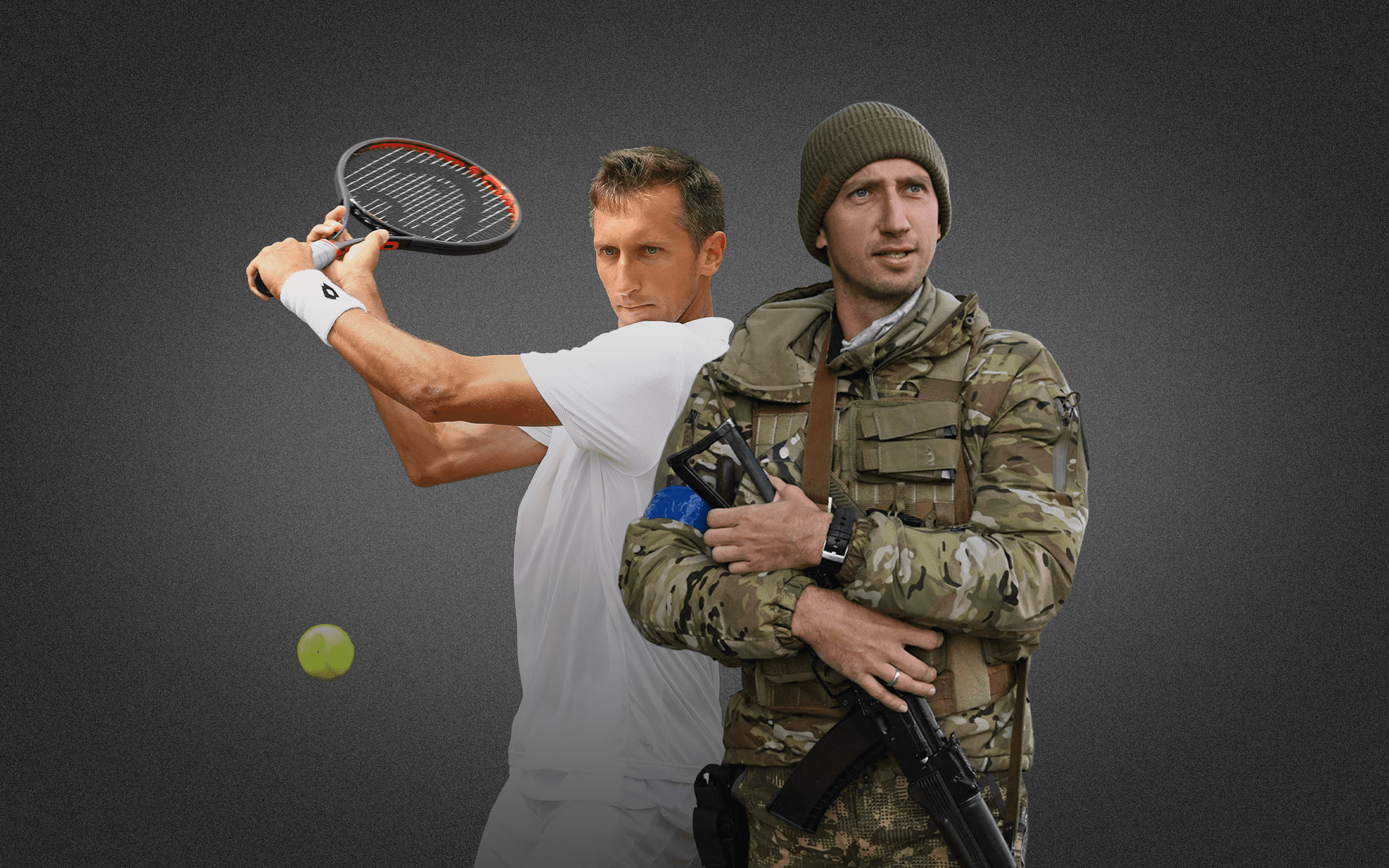

Game, Set, Drone Strike: Tennis Star Who Beat Federer Now Serves in Ukraine’s Elite Forces

Sergiy Stakhovsky once defeated Roger Federer on the tennis court. Today, the seven-time ATP champion is trading rackets for drones as part of Ukraine’s elite Alpha unit, striking deep inside Russia.

For more than two decades, Ukrainian Sergiy Stakhovsky dedicated his life to tennis. But for the past three years, Stakhovsky has been a fighter with Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU). If his name once appeared in headlines for tennis results, now it surfaces for something entirely different — launching top-secret drones against Russia as part of the elite “Alpha” Center for Special Operations.

“My travel schedule used to be: Paris, Wimbledon, Melbourne, New York,” he said. “Over the past three years, it’s been Bakhmut, Avdiivka, Izium, Lyman. Once, in the Kharkiv region, a rocket exploded right in front of our armored vehicle. We were blown into the bushes, climbed out battered, and then spent hours dodging artillery fire.”

This is how Stakhovsky recalls one of the most vivid episodes of his new life. But defining moments have never been in short supply for him.

Born and raised in Kyiv, the son of a doctor and a university lecturer, Sergiy started playing tennis early. At age 12, his family held a council to decide whether he should continue, given the cost and sacrifice. He chose to persist.

“When a few years later I played the junior US Open final against Andy Murray, it became clear I had a chance to make it in tennis. All those people who used to say, ‘You won’t succeed, only a hundred players make a living, why are your parents wasting money?’—suddenly they were cheering me on. But I truly believed in my path after I won the 2008 Zagreb Indoors.”

That year, ranked 209th in the world, Stakhovsky stunned Croatia’s Ivan Ljubičić—a former world No. 3—to claim his first ATP title. It would not be his last upset, nor his last headline.

The match no one asked for

“After February 24, 2022, I got hundreds, maybe thousands of messages from the tennis community—Djokovic, Federer, everyone,” said Sergiy. “I couldn’t even keep up. Fans wrote too. Back then, Europeans felt the war was close; missile strikes in Ukraine sounded loud to them. Now that seems to have changed. The civilized world acts like it’s forgotten. At first, governments said, ‘Let’s wait and see,’ while ordinary people rushed to help. Now it’s the opposite—citizens pay little attention, but governments understand the consequences if Ukraine loses.”

Stakhovsky stresses that Russia has long told its people Ukrainians were their enemies—propaganda largely ignored in Ukraine. But when the full-scale invasion began, domestic support inside Russia was overwhelming.

“They literally celebrated missiles hitting peaceful cities,” he says. “Now they talk about capturing Berlin and Paris, about striking the US. And the world keeps dismissing it as talk. If Ukraine doesn’t win, you or your children will face Russians on the battlefield.”

For Stakhovsky, the war became real with a phone call.

“My mom called early in the morning: ‘There are massive explosions everywhere.’ I turned on the TV and saw something I’ll never forget — my hometown skyline of Kyiv lit with fire.”

At the time, he was living abroad, but weeks before the invasion, he had already signed up for Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces.

“I hoped that if enough people enlisted, Russia might think twice. They’d see that Ukrainians were ready to defend themselves. But it didn’t stop them.”

Days after the invasion began, he said goodbye to his family and left for Ukraine. He never told his three children he was going to war.

No tie-breaks here—just survival

“I honestly love tennis,” says Sergiy. “I enjoy being on the court. But after the invasion, I didn’t watch tennis for almost two and a half years. Sport and war have similarities: you fight to the end when you’re exhausted. But lose a match, and you play again in a few days. Lose in war, and you lose lives — your own or your comrades’.”

Tennis, he notes, is often more about losses than wins.

“You lose regularly, because no one wins every week. Even Djokovic, Nadal, and Federer—they lost 7–10 matches a year. Tennis is mostly about losing.”

For Stakhovsky, the word “loss” carries a special connection to Federer.

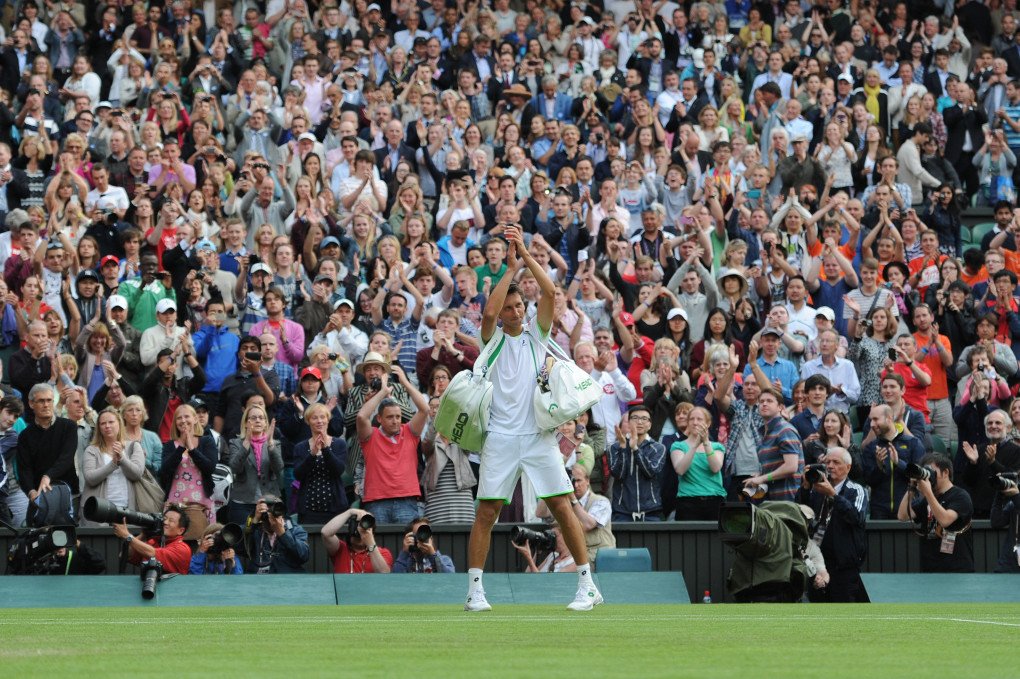

In 2013, Federer was already a legend, a seven-time Wimbledon champion, and virtually untouchable on grass. Yet Stakhovsky shocked him in four sets in the second round, ending Federer’s streak of 36 consecutive Grand Slam quarterfinals.

“That victory taught me so much about myself,” says Sergiy. “I spent my career in the era of three perfect players — Nadal, Djokovic, Federer. For 15 years, they allowed almost no one else to win. They were on another level. And suddenly you realize they’re human, too. That gives you a new kind of belief.”

Stakhovsky’s career also included wins at the St. Petersburg Open and the Kremlin Cup. Prominent Russian players were among his tennis circle.

“Until 2014, I was close with Mikhail Youzhny—I’m even godfather to his son,” he says. “But then Crimea was annexed, and he tried to tell me it was geopolitics, when in reality it was just stealing land. I also knew Andrey Rublev. When Russia’s full-scale invasion started, he played in Dubai and wrote ‘Stop the war’ on a camera. Back then, it seemed to mean something. Now, I don’t talk to anyone from Russia.”

Russian players remain on tour, stripped only of their flag.

From baseline to frontline

“When I came back to Ukraine in February 2022, I contacted some military friends,” sayd Sergiy. “One invited me to join the Alpha Center of the SBU. That’s an elite unit.”

At first, Stakhovsky served in a mortar crew—firing 120mm rounds from 1.5 km, and 82mm mortars from just 700 meters.

Later, he worked with small drones. Now, his missions reach far deeper into Russia.

“Most recently: Engels, Toropets, Toropets-2,” he lists.

Engels—a Russian airbase housing strategic bombers—lies 750 km from Ukraine. In March 2025, Ukrainian long-range drones destroyed a missile stockpile there.

Toropets—a major Russian missile depot in Tver region—erupted in September 2024 with such force it triggered a 2.8-magnitude earthquake, reported the UK’s Defense Ministry.

Days later, Toropets was hit again, alongside another depot in the Krasnodar region.

“Some of our unit also took part in Operation Spiderweb,” Sergiy adds.

Operation Spiderweb—a daring strike in which FPV drones launched from trucks hit four Russian airbases, damaging 41 aircraft and inflicting $7 billion in losses.

“These are top-level operations. It’s always satisfying to read the panic in Russian pro-war channels. Makes you smile.”

Alpha has destroyed over $5 billion worth of Russian equipment—not even counting strategic plants, refineries, and other major targets, says Sergiy.

“Small groups can do big things,” he says. “So join up. Recruitment standards are slightly eased now in terms of fitness. But even as a professional athlete, I was shocked. If these are the relaxed tests, how tough were they before?”

In summer 2025, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky signed a law expanding Alpha’s ranks to at least 10,000. The elite unit has proven its effectiveness, thanks in part to a seven-time ATP champion.

As our conversation ends, Stakhovsky notes he has another mission that evening. Soon enough, he says, the world may once again read about his latest victory in the headlines.

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)