- Category

- War in Ukraine

How a Ukrainian Teen Created Anti-Drone Ammo That Saves Soldiers' Lives

At 16, Yurii launched a start-up to design anti-drone ammunition. Now 18, he balances school, prototypes, and a call to defend Ukraine’s skies.

We arranged to meet at 8 p.m. on August 31, on the eve of the start of the 2025 school year in Ukraine. Yurii had turned 18 a few months earlier, but when we exchanged a few messages on Telegram before meeting, I imagined him to be at least ten years older.

We agreed to meet at the small café on the western edge of Kyiv’s Shuliavka district—a semi-industrial, semi-residential neighborhood. I saw more soldiers than I am used to spotting downtown, as well as students, coming back from the huge and historical neighboring universities.

During the 1905 Revolution in the Russian Empire, students from the newly founded Kyiv Polytechnic Institute joined local workers to declare the short-lived “Shuliavka Republic”. Russian Tsar Nicholas II’s troops crushed it within days, but the episode became a lasting symbol of Kyiv’s resistance.

Shuliavka also saw heavy fighting in February 2022, at the very beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, particularly near the Kyiv Zoo. None of Russia’s attempts to take a foothold succeeded. Since then, the district—like much of Kyiv—has often been targeted by Shahed attack drones and missiles. And the intensity is growing. In the summer of 2025 alone, Russia attacked Ukraine with 10,425 Shahed-type long-range drones and hundreds of missiles.

When Yurii appeared in the distance, we recognized each other instantly. He looked no older than 18, and could easily pass for 16. Hard to imagine, but for the past two years, he has worked as an entrepreneur in Ukraine’s defense industry—the reason I set up this interview.

He immediately asked me not to reveal his identity. “Russians have easy access to company status and revenue registries in Ukraine,” he said. “Firms linked to the war effort that make around $200,000 a year become targets for drones. Those making more than $5 million a year face cruise and ballistic missiles. Staying anonymous brings its own challenges, but I don’t want to take risks right now.”

From 11th-grader to drone-killer entrepreneur

Back in 2023, Yurii was still in 11th grade—frustrated with school and immersed in YouTube videos about military equipment, DIY engineering, and 3D printing. His neighborhood was under constant attack. Too young to enlist in the Armed Forces, he searched for another way to contribute.

The motivation was to bring benefit to the country. School was moving too slowly, my neighborhood was being bombed, and I wanted to do something useful.

Yurii

So far, Ukraine has relied on voluntary enlistment contracts for 18–24-year-olds. In parallel, units such as Khartia, Azov, and the 3rd Assault Brigade have courted the country’s youth. Too young to enlist, Yurii turned to a defense tech incubator, where he first pitched quieter FPV drone propellers. The idea failed, so he pivoted to anti-drone munitions.

“On the battlefield, 75% of injuries now come from drones,” he says. “Drones could be the biggest threat to individuals in the coming years. Creating anti-drone systems can truly save lives.”

Interviewed by Politico, on August 27 2025, the commander of the 429th Separate Regiment of Unmanned Systems, Yurii Fedorenko, said Ukraine needs 350,000 drones each month to “reach parity” with Russia, which continues to recruit 25,000–30,000 troops monthly. Ukraine’s reliance on unmanned systems has become existential, given its limited resources in the fight against a much larger country with four to five times its population. The same applies to anti-drone systems.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the drone and anti-drone industry has been booming worldwide. Both Ukraine and Russia locked in a technological spiral, constently adapting warfare with even more unmanned systems. According to Defense News, “Advancements in artificial intelligence and drone warfare continue to bear fruit, prompting many nations’ militaries to rethink their defense strategies and turn to unexpected companies to bolster their armories.”

Playing games, building weapons

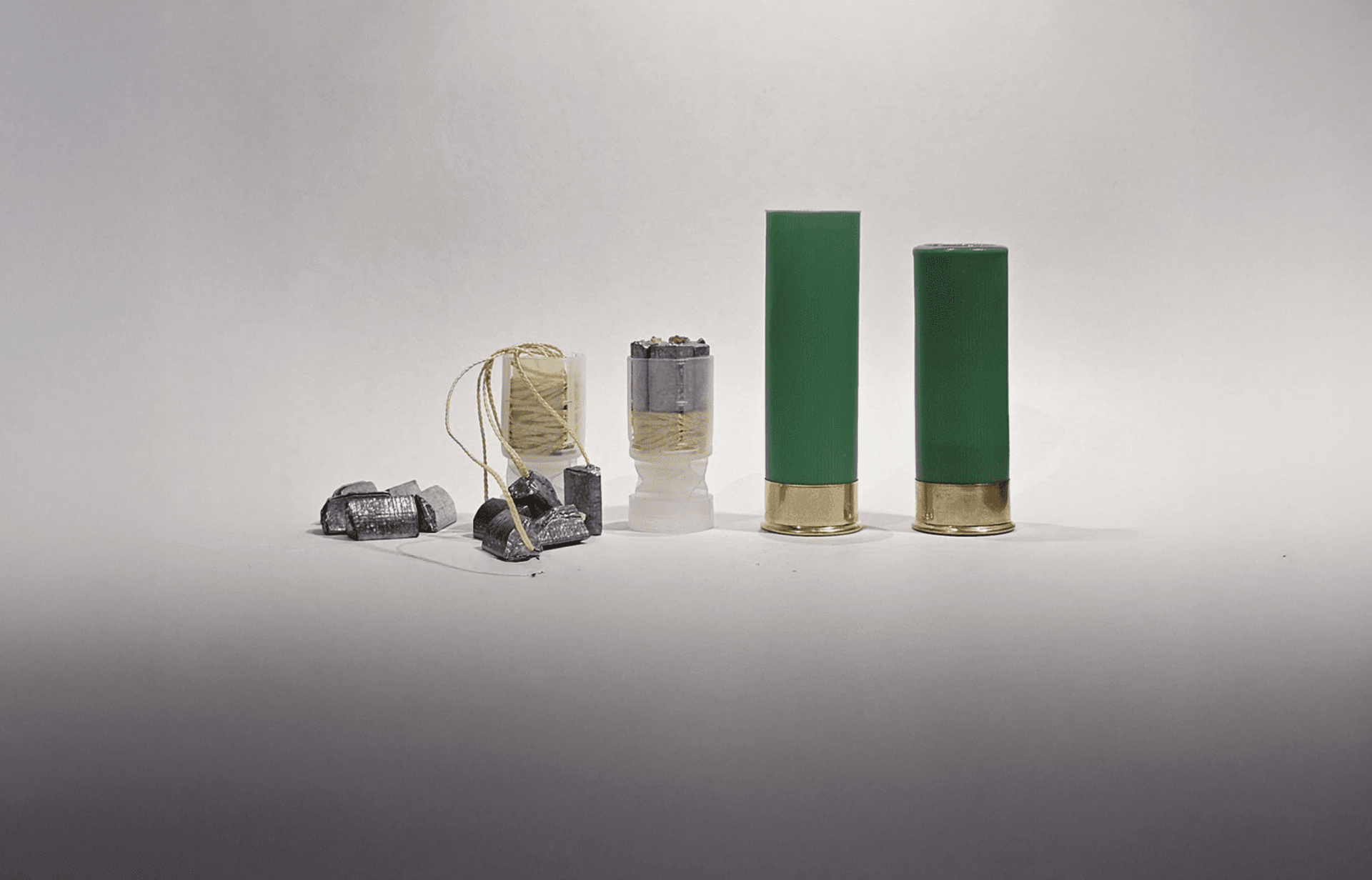

The idea came while Yurii was playing a first-person shooter video game with a friend who knew a bit about ammunition. “It was during those gamers' discussions that the idea of anti-drone net rounds for a grenade launcher came to me,” he said.

Once their first prototype was ready, Yurii’s partner suggested pitching the idea to the Presidential Brigade. Yurii hesitated, but they tried anyway. A soldier looked at it and said: “Oh, cool, a grenade-launcher anti-drone munition.” They left him a sample, but in the end the unit couldn’t help because it lacked testing procedures.

Soon after, while going door to door at military camps, the 3rd Assault Brigade welcomed his small team. An officer listened to his pitch, examined the first prototype, and asked what they did outside of this project. Yurii and his team replied: “We are still in school.” The officer was stunned—and amused.

What kind of children in the world can make ammunition? Ukrainian children, of course!

Third Assault Brigade officer

Still, he took them seriously, asked what they needed to run initial tests, and promised to get back to them in a few weeks. Beyond its flashy ad campaigns and the youth of its fighters, the 3rd Assault Brigade is also known for innovative drone use. In summer 2025 it carried out the first prisoner capture in history conducted solely with aerial and ground drones.

A few weeks later, Yurii’s team was invited to a training center to test the prototype—and, crucially, to attach the explosive charge. Handling explosives in Ukraine is strictly regulated, especially during wartime. Under Article 263 of the Criminal Code, violations carry prison sentences, and being a minor makes it impossible to obtain any authorization.

After the first tests, the military added, “Okay, guys, this is cool, but in our brigade, there are more shotguns than grenade launchers. So make us the same thing for shotguns.” Within days, Yurii and his team switched calibers and delivered the first samples to the unit.

Scaling challenges

Two weeks later, they received a message from the unit officer: “It f***** works!”. Soon after, he ordered 100 of them for real-combat testing.

This speed in decision-making is both a strength and a weakness of Ukraine’s wartime technological industries. “We have a lot of private companies appearing, and they move faster than state enterprises,” Yurii said. “But there is no system for everything to quickly move from a start-up to the army. Because of this, many things remain prototypes.”

Scaling is still Russia’s advantage. “They can make a lot, even if it isn’t perfect,” Yurii admitted, citing the appearance—and quick massive use—of Russian fiber-optic drones during the 2024 Kursk operation.

They were so astonished by this first “order” that they didn’t think about the problems of scaling up production. Watching a training video from the 3rd Assault Brigade, they recognized their munition being tested. The round jammed. The instructor joked, “Now I’m going to die, because it didn’t fire.”

“At that moment, I was really scared, because I realized—if something goes wrong, a person could be killed.”

Yurii

The discouragement didn’t last. A special forces unit called from the Kursk front: “We tested your stuff—it was awesome!” It reported shooting down one Mavic at 50 meters and two Russian FPVs with shotgun rounds. That was when Yurii knew his idea worked and had already saved lives.

A generation at war

The son of an accountant and an agronomist, Yurii was hardly destined to become a defense-tech entrepreneur. “My parents, honestly, were shocked at first. But when they saw that what I was doing was useful, they supported me,” he said.

Since then, Yurii has followed the path of a typical start-up—programming, testing, business development, and searching for partners. He is waiting for a grant decision from Brave1, Ukraine’s defense-tech cluster.

He believes Ukraine must rely on its own resources and build scalable, affordable systems to defend itself. “Patriots or IRIS are good, but there are few of them,” he said, “We need cheap ammunition that can be mass-produced so every city has protection.”

Now an adult, Yurii is torn between continuing his studies, devoting himself fully to his start-up, or joining the army. For now, he combines all three—following some classes on his phone, while testing his ammunition at military bases, and taking part in Centuria, the youth paramilitary camp of the 3rd Assault Brigade.

Even though he never asked for it, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has become Yurii’s war too. His generation is growing up with it, and some, like Yurii, refuse to stay on the sidelines. “I am not afraid to die, but I want to be useful first,” he said shortly before we parted ways.

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)