- Category

- Anti-Fake

How Russia Tries to Control Your Social Media Feed: The Baltic States Case

From nostalgic TikToks to fake Facebook groups, Russia is flooding the Baltic states with disinformation designed to stir division. Memes, mask manipulation, and Russian-speaking communities are weaponized to weaken the region from within.

When Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia moved to ban Russian state TV channels and news sites in 2022, it looked like a decisive victory for their information security. For decades, Moscow’s state-controlled broadcasters had been the main vector for pushing pro-Kremlin narratives into these countries’ Russian-speaking communities.

But now, Kremlin-linked accounts have built a thriving ecosystem across Facebook, TikTok, Telegram, and X, pumping out everything from half-truths to outright fabrications about “protecting Russian speakers,” supposed “oppression” by Baltic governments, and the decay of Western institutions.

Investigators from Ukraine’s Centre for Countering Disinformation found, in just a short sampling window, six Facebook pages with 123,000 followers, nine Telegram channels with 78,000 readers, a dozen TikTok accounts with 162,000 followers, and 15 X accounts reaching over 211,000 people. And that’s just the tip; it’s only a sample size of a much larger network.

The content is highly adaptable and personalized. It blends sheer volume with precision targeting and is financed from the Russian state budget through grant systems or direct contracting.

The old story, told in a new way

The core false narratives haven’t changed much since the Soviet era—they’ve just been recalibrated for our current algorithm-driven reality. Among them:

The EU is “provoking” war with Russia in the Baltic states and preparing to invade.

Russian speakers face systemic discrimination and need Moscow’s protection.

The Baltic states are “colonies” of NATO and the US, incapable of true independence.

Aid to Ukraine “harms” local citizens and drains resources.

Life under the USSR was more stable, affordable, and fair.

Instead of hammering these lines through heavy-handed news segments, the operators weave them into the digital fabric of everyday life.

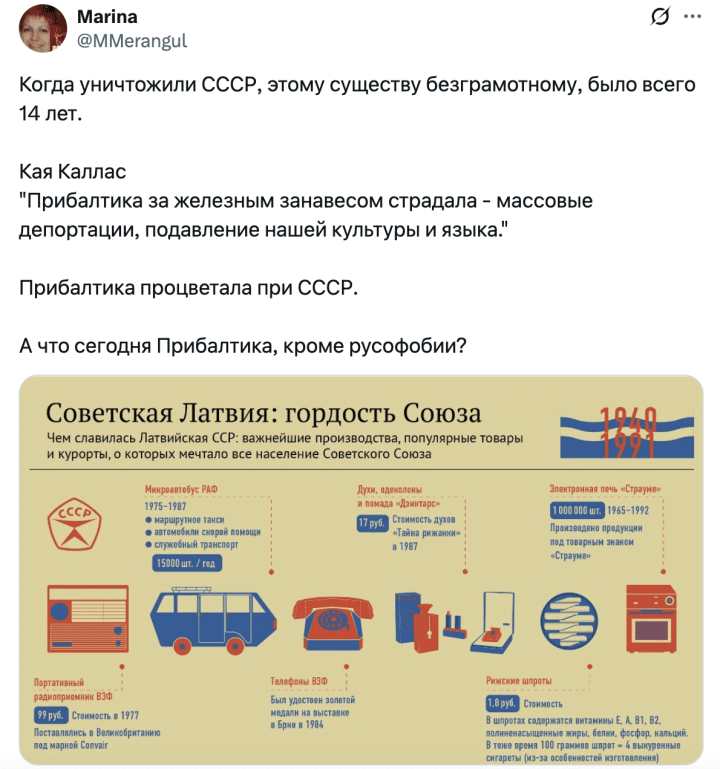

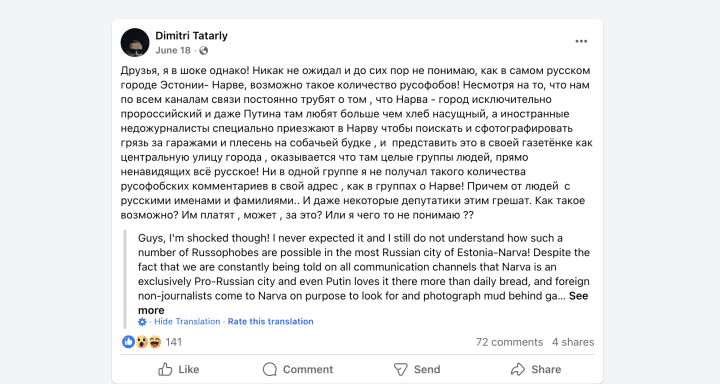

On Facebook, that means embedding propaganda in groups with friendly and approachable names like Таллинцы (“Tallinners”) or Русскоязычная Эстония (“Russian-speaking Estonia”). These pages mix neighborhood gossip, Soviet nostalgia posts, and lighthearted memes with Kremlin talking points about NATO aggression, EU incompetence, and the dangers of helping Ukraine. Comments sections are peppered with “ordinary users” (often fake accounts) insisting that “life was better with Russia” or that “Ukrainian refugees are taking jobs and housing.”

Meanwhile, most surveys show no big nostalgia for the Soviet Union. In a 2017 survey published by Pew Research Center, 75% of Estonians viewed the dissolution of the USSR as a positive development, while only 15% saw it negatively. Similarly, in Latvia, 53% of respondents in a 2017 Pew survey agreed that the collapse was beneficial, though 30% felt it was harmful. In Lithuania, 62% of people shared this positive view, with just 23% dissenting.

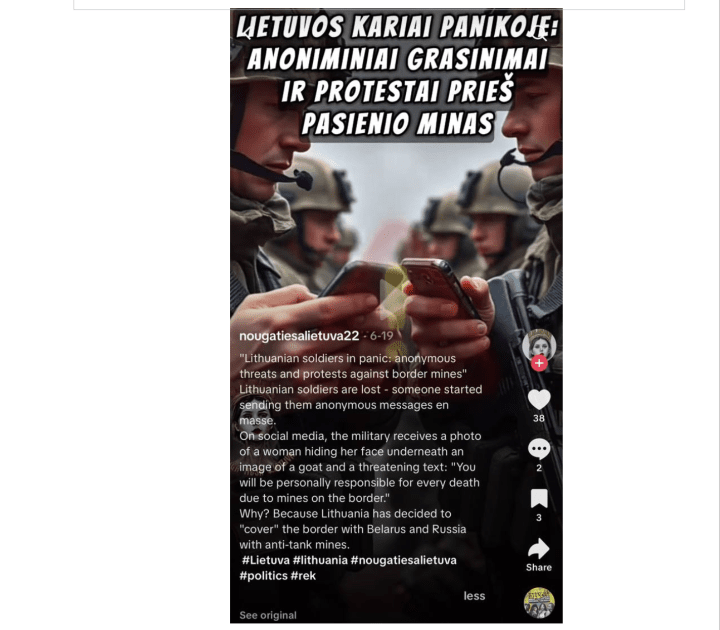

TikTok is more performative. Influencers package anti-EU and anti-NATO content into dance trends, comedy skits, or even music. One viral track, “Вся Прибалтика прекрасна” (“All the Baltics are Beautiful”), ridicules Baltic governments as corrupt and laments the loss of Soviet-era industry. The song racked up at least 1.3 million views across nearly 200 videos, many stitched with footage of crumbling factories or rising prices. The framing is simple: people aren’t to blame, politicians are. And in these clips, the EU is the villain.

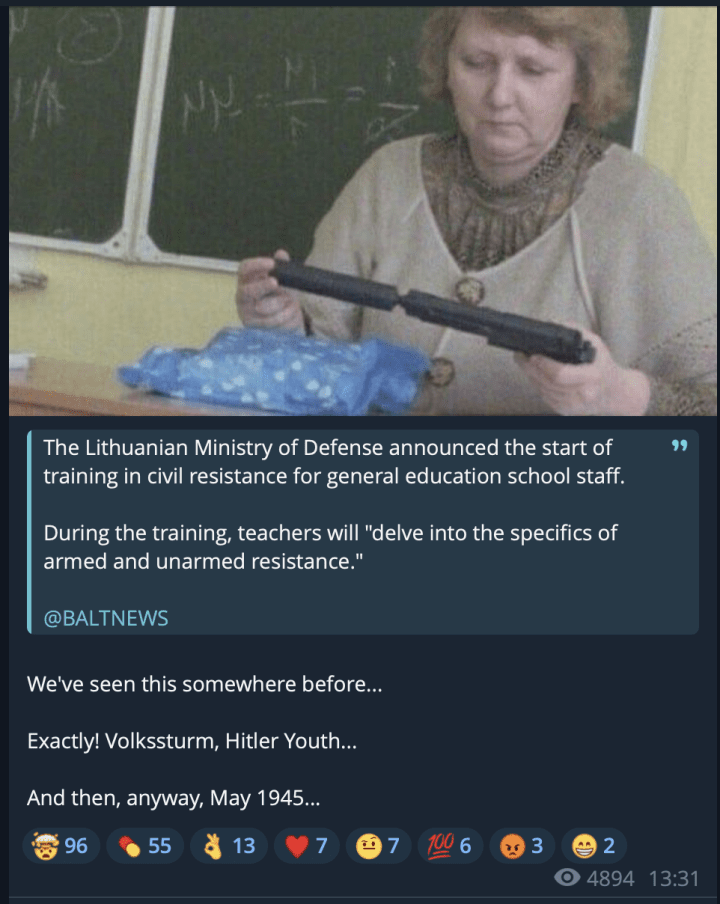

Telegram channels operate like parallel newsrooms, pumping out a steady flow of content that mixes hard news with opinion, historical revisionism, and cultural nostalgia. Some of the biggest channels, like Baltnews and Антифашисты Прибалтики (“Antifascists of the Baltics”), openly repost Russian state media content. Others package their work as “local” reporting, downplaying their links to Moscow while pushing the same talking points: the Baltic militaries are weak, NATO expansion is dangerous, and cooperation with Russia is both inevitable and beneficial.

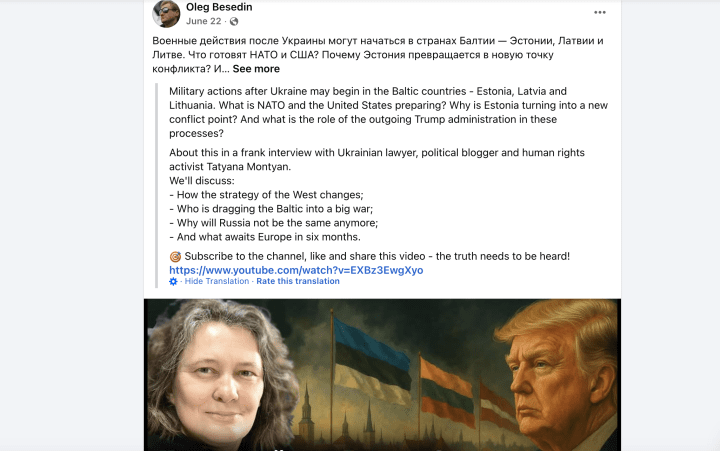

On X (Twitter), the tone is more blunt. Politicians are mocked in crude language. Former Estonian prime minister and current EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas has been a regular target, smeared with fabricated claims about incompetence or corruption. Militaries are portrayed as incapable of defending themselves, with any Baltic deterrence measures against a potential Russian invasion are framed as needless provocations.

The architecture of influence

This isn’t freelance trolling. OSINT data gathered by the CCD showed that the Russian Presidential Administration’s Directorate oversees the campaigns for Cross-Border Cooperation, led by Alexei Filatov and reporting to Deputy Chief Dmitry Kozak. The apparatus works through Kremlin-backed NGOs like Historical Memory, which romanticizes the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states, and the Russian Association for Baltic Studies, which produces “expert” commentary skewed toward Moscow’s party line.

These organizations are formally “non-governmental” but receive state funding through grants and direct contracts. To avoid prosecution, much of the content is generated from Russia or Belarus. Baltic citizens who have relocated to Russia sometimes find work producing tailored content for audiences back home.

The playbook is refined and deliberate: normalize Russian political and cultural influence, erode trust in NATO and the EU, and lay the groundwork for justifying a “military solution” in the Baltic states under the guise of defending Russian speakers. The report warns that, taken to its conclusion, this narrative could underpin an actual invasion within four to six years.

Campaigns in motion

Recent examples show how quickly the machine adapts to new events.

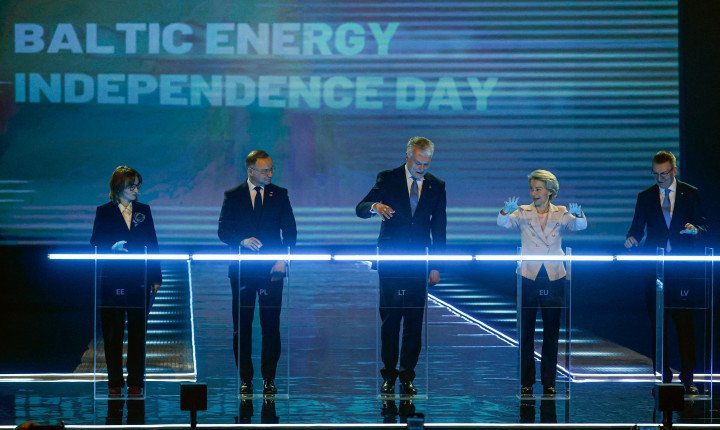

When Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia synchronized their power grids with Europe’s ENTSO-E in February 2025, Russian media immediately pumped out claims of looming blackouts, soaring electricity prices, and “losing a reliable partner” in Moscow. The volume of propaganda about Lithuania’s energy situation more than doubled in the weeks after the switch.

When Kaja Kallas took her EU post, bot networks launched a smear campaign alleging she had been sidelined from sensitive EU documents over incompetence—an entirely fabricated story designed to undermine her authority.

And in 2024, fake reports spread about NATO troops allegedly being sent from the Baltic countries to Ukraine. A coordinated disinformation campaign across Lithuanian Facebook and Telegram began with claims that these countries were prepared to fight abroad. It evolved into rumors about the deployment of troops to Ukraine, followed by fabricated videos of “Ukrainian soldiers” thanking Lithuania for its support and encouraging further involvement in the fight.

Even minor local incidents are weaponized. In Latvia, a rumor spread that a teacher forced students to sing the Ukrainian national anthem. Telegram and TikTok amplified it into a narrative about “brainwashing children” and “neglecting patriotism,” tying it to the larger trope of Western cultural imposition.

Weaponizing the Russian-speaking minority

Moscow is especially interested in the Baltic states because of their sizeable Russian-speaking minorities, geographic position on NATO’s eastern flank, and history of Soviet rule. Propaganda here is also about manufacturing a casus belli.

In the Kremlin’s narrative, discrimination against Russian speakers can be “corrected” through intervention. This was the pretext used for Crimea in 2014 and for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The same language now circulates in Baltic-focused channels, suggesting that Moscow is building the political cover it would need for future aggression.

At the same time, by eroding trust in EU and NATO institutions, the campaigns aim to weaken the region’s cohesion from within. If Baltic citizens come to doubt the value of Western alliances—or see them as actively harmful—then the Kremlin doesn’t need tanks to gain influence.

Overall, the Kremlin propaganda targets two distinct audiences, Rihards Bambals, a strategic communications expert from Latvia’s State Chancellery, explained to the Latvian investigative outlet Re: Baltica. The first is the Russian domestic audience, bombarded with negative stories about Europe to distract from Russia’s own economic difficulties. The second targets Baltic and international audiences, aiming to discredit the Baltic states by promoting narratives of the so-called “russophobia, economic failure, and a resurgence of Nazism.”

The new normal

The lesson from the Baltic states is stark: the Kremlin no longer needs an expensive TV studio to reach you. It only needs the apps you already open every day.

Unlike traditional media, social platforms allow operators to micro-target audiences, disguise propaganda as entertainment or community chatter, and avoid direct government regulation. Content can be localized down to the city or neighborhood level, making it feel organic even when it’s centrally directed from Moscow.

For now, the battleground is informational. But as the report makes clear, information war is rarely an end in itself. It’s preparation. And in the Baltic case, that preparation looks alarmingly like the groundwork for something far more tangible.

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)