- Category

- Anti-Fake

NATO Isn’t the Reason Putin Invaded Ukraine: A Point-by-Point Breakdown

Here’s a step-by-step guide on one of the Kremlin’s most misleading claims: that NATO’s expansion left Putin no choice but to invade Ukraine. The facts about NATO and Ukraine tell a different story.

Despite the Kremlin’s insistence that NATO expansion provoked Russia’s war against Ukraine, the claim falls apart under scrutiny. The alliance has been on Russia’s doorstep for decades. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have been members since 2004, while Türkiye and Norway have belonged to NATO since it was founded in 1949. In 2023, Finland joined as well, extending the alliance’s frontier even further along Russia’s border. Russia has never dared to challenge any of these countries directly.

NATO, by design, is not an offensive force poised to attack. Even today, while Russia wages war against Ukraine, launching drones that crash into NATO territory, the alliance remains relatively lightly armed along its eastern flank and does not station missiles capable of striking deep into Russian territory. Its mission has always been to prevent conflict through collective security, not to provoke one.

Ukraine and NATO before 2014: cooperation, not membership

First, is Ukraine a member of NATO? No — it is not.

Since gaining independence in 1991, Ukraine expressed interest in cooperating with NATO but did not pursue membership. This interest was formalized through Ukraine’s participation in NATO's North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC) in March 1992.

In 1994, Ukraine joined NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program, the same one Russia joined, which allowed non-NATO countries to collaborate with NATO on military and security matters without becoming full members. This was a significant step, but it was about cooperation, not membership.

Ukraine began preparing for NATO membership under the NATO–Ukraine Action Plan at the request of Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma in 2002. After the Bosnian War (1992–1995), during which NATO led air strikes and peacekeeping missions, and the Kosovo War, it became clear that European security crises could escalate quickly and that NATO was the key force able to contain and resolve them.

NATO issued the NATO–Ukraine Action Plan in 2002, providing a strategic framework for Ukraine’s aspirations toward full integration into Euro-Atlantic security structures. It outlined specific objectives and priorities in areas such as political, economic, military, and defense matters, aiming to align Ukraine more closely with NATO standards.

Although the initiative marked a pivotal moment in Ukraine’s relationship with NATO, signaling a clear intent to deepen cooperation and move closer to potential membership, Ukraine still did not formally apply for it and instead focused on reforming its military and aligning with NATO’s standards.

Russia’s efforts to seize parts of Ukraine started long before NATO membership was seriously discussed for Kyiv. As early as 1992–1993, a year after Ukraine declared independence, Moscow backed political movements in Crimea calling for separation from Ukraine and reintegration with Russia.

Decades later, in 2014, Russia invaded and orchestrated fake referendums in Crimea to justify its illegal attempt at annexation of the peninsula. In the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, Russian operatives stoked unrest and armed local militants, leading to sham votes and the self-declared “people’s republics” that have served as Moscow’s proxy foothold in eastern Ukraine.

Moreover, for years, the Kremlin has used the distribution of Russian passports in these occupied areas as a tool to claim “protection” over Ukrainian citizens, another manufactured pretext for intervention. These aggressive actions all began while Ukraine was officially a neutral country and before any concrete NATO accession plan was on the table.

NATO’s defensive nature

There are no NATO troops in Ukraine, as Ukraine is not a NATO member and the alliance does not maintain combat forces or military bases on Ukrainian soil. NATO countries like the United States and the United Kingdom do provide weapons and train Ukrainian soldiers on their territory, but are not fighting or posted inside of Ukraine.

NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, was created in 1949 as a defensive alliance to help prevent another world war and to contain Soviet expansion during the Cold War. At its core, it is a pact of mutual protection—an agreement among sovereign countries to stand together in the face of external threats.

The alliance’s primary goal, as outlined in Article 5 of the NATO treaty, is collective defense: “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all.”

That’s exactly why countries like Finland and Sweden, countries long committed to neutrality, chose to apply for NATO membership in 2022 after witnessing Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This roughly doubled the length of NATO’s land border with Russia.

Even the Soviet Union, under Nikita Khrushchev, sought to join NATO in 1954, hoping to guarantee European security. The bid was rejected because it was presented as a gesture to ease post-Stalin tensions and “strengthen peace in Europe.” Western leaders, however, saw this as a maneuver to block West Germany’s rearmament and undermine the alliance from within.

“It was not realistic that the USSR would accept the requirements of NATO,” said Helen Kurvits in an article for Release Peace Magazine, headquartered in the Hague. “The most important requirements concerned the control over its military planning and the securing of democratic rights in the Soviet Union, as well as in the countries that fell within its sphere of influence.”

This prompted Moscow to establish its own rival bloc: the Warsaw Pact in 1955, a collective defense alliance of Eastern Bloc states that lasted until the Soviet collapse in 1991.

Equally misleading is Moscow’s claim that NATO broke a promise not to expand “an inch eastward.” Numerous archival documents show that no legally binding commitment was ever made, and after gaining independence from the Soviet Union, the states voluntarily pursued NATO membership for security and protection.

The Russian “not one inch” myth

In her book Not One Inch, published in 2021, historian and Cold War expert Mary Sarotte reveals that during the discussions about Germany’s reunification, the US Secretary of State under President George H W Bush, James Baker, suggested to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO wouldn’t expand “one inch” to the east in return for the Soviet Union agreeing to allow Germany to join NATO. This is one of the base arguments in the “NATO-russia conflict,” so often brought up by Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

This was a suggestion, not a formal promise.

“Yes, it’s definitely a myth,” Gorbachev himself has confirmed, saying that no formal agreement was made, and that this was more of an informal comment, not a binding treaty.

This claim, however, has been repeatedly echoed and distorted, especially by Putin, turning it into a widely accepted narrative in the media.

What is conveniently overlooked is that Gorbachev’s successor, Soviet leader Boris Yeltsin, signed the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, an actual physical document that committed Russia to respecting Ukraine’s sovereignty and has since been flagrantly violated.

How many countries joined NATO after the fall of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union signed the Charter of Paris in November 1990, promising to “fully recognize the freedom of States to choose their own security arrangements.” Later, in 1997, Russia and NATO signed the NATO–Russia Founding Act, which also confirmed the “inherent right” of all countries to decide how to ensure their own security.

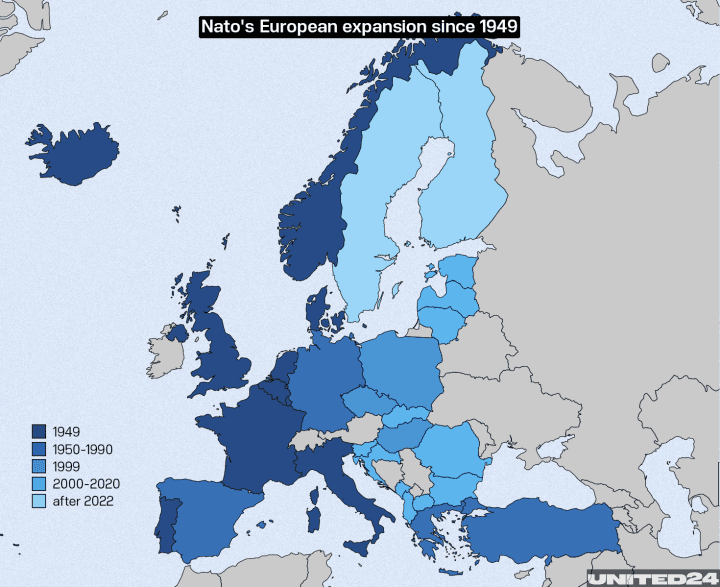

1999 – 3 countries: Czechia, Hungary, Poland

2004 – 7 countries: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia

2009 – 2 countries: Albania, Croatia

2017 – 1 country: Montenegro

2020 – 1 country: North Macedonia

2023 – 1 country: Finland

2024 – 1 country: Sweden

After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, countries in Eastern and Central Europe, once under Soviet influence or direct control, began to seek alliances with the West. These countries included Poland, Czechia, and Hungary, which joined in 1999. NATO’s “open door” policy, which allows any European country that meets certain criteria to join, played a key role in this shift. Former Soviet republics and Warsaw Pact members were eager to secure their independence and stability by joining NATO, which would provide a strong security guarantee against any potential Russian aggression.

NATO's expansion into Eastern Europe was primarily driven by the countries themselves, seeking security guarantees in the post-Cold War period. Many Eastern and Central European countries faced new challenges in 1991 regarding their security, political stability, and economic development. These countries wanted to ensure their sovereignty and independence, especially given Russia’s lingering influence in the region.

The ex-Soviet state’s NATO ascensions are, in fact, a stark reminder of the system’s failure to inspire loyalty at home or among its neighbors. The ISW report Weakness is Lethal: Why Putin Invaded Ukraine and How the War Must End published on October 1, 2023 comes to the conclusion that, “The ‘color revolutions’ that so alarmed Putin were, after all, the manifestations of those countries daring to choose the West, or, rather the way of life, governance and values the West represented, over Moscow.”

For centuries, Russia has tried to stay safe by controlling its neighbours. Its military believes wars should be fought outside Russia’s own borders. There’s no proof that Russia would have changed this mindset even if the EU and NATO hadn’t expanded. As the ISW report puts it, “No evidence suggests that Putin’s or the Russian military’s posture prioritized building large mechanized forces on the Russian borders with NATO to defend against invasion. Russia deployed the principal units designed to protect Russia from NATO to Ukraine.”

NATO works with Russia, trying to strengthen cooperation

When NATO expansion discussions gained momentum in the early 1990s, many experts debated how to admit new members while maintaining stability in Europe. Countries in Central and Eastern Europe actively sought NATO membership to secure their independence and prevent any return of Russian domination after decades under the Soviet sphere.

To foster broader security and cooperation, NATO invited Russia to participate in a range of joint initiatives. In 1994, the alliance launched the Partnership for Peace, which included nearly every European country, including Russia, to promote dialogue and military cooperation.

In 1997, NATO and Russia created the Permanent Joint Council, followed by the NATO-Russia Council in 2002, giving Moscow a forum to engage directly with NATO members. Russia was also integrated into the IMF, the World Bank, the G7 (then the G8), and the World Trade Organization, part of a broader effort to anchor Russia in the international system as a cooperative partner.

NATO’s policies reflected this cooperative approach. In 1996, NATO publicly stated it had no intention to deploy nuclear weapons or large combat forces in new member states. This commitment was formalized in the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, which made clear that enlargement aimed to strengthen Europe’s stable security architecture rather than threaten Russia.

Throughout the late 1990s and 2000s, Russia used the “NATO expansion” narrative and Western support for democratic movements as excuses to interfere in its neighbors.

Putin and his government framed democratic movements like Georgia’s Rose Revolution (2003) and Ukraine’s Orange Revolution (2004) as Western interventions, laying the groundwork to justify later military aggression.

2008: Ukraine’s NATO bid stalls at the Bucharest Summit

Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution marked a decisive shift in the country’s path toward the West. Triggered by widespread allegations of election fraud benefiting the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych, the mass protests ultimately secured a new election and brought the pro-European Viktor Yushchenko to power. The revolution cemented Ukraine’s push to limit Moscow’s influence and pursue closer ties with Western Europe and NATO.

The Ukrainian President, Viktor Yushchenko, advocated for stronger national defense architecture viewing NATO and the EU as essential “guarantors of security and stability.”

However, NATO did not grant Ukraine a Membership Action Plan (MAP), which is usually seen as the final step before full membership.

Instead, NATO issued a statement acknowledging Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations but refrained from offering a clear membership pathway at that time, partly due to Russia’s strong opposition and internal NATO disagreements.

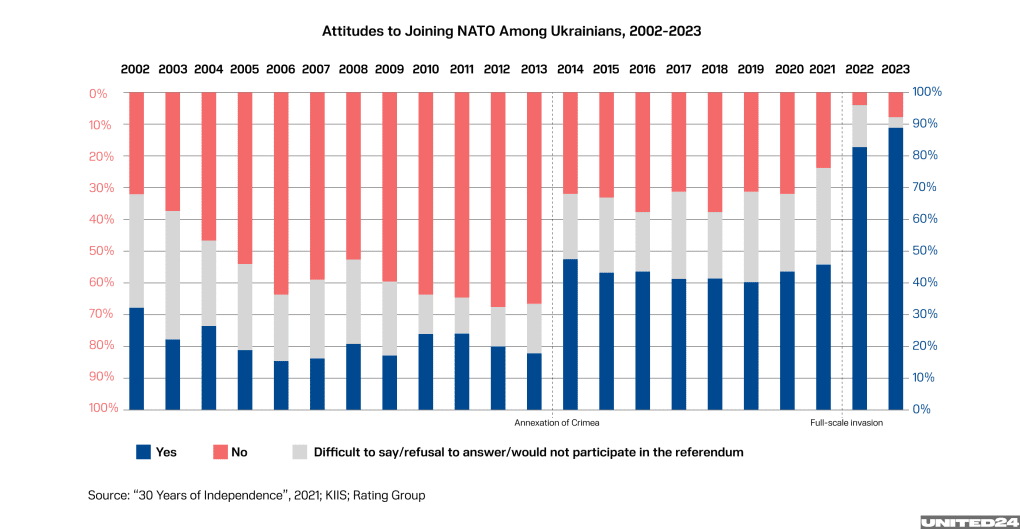

According to a poll conducted by the Ukrainian media outlet, Kyiv Post, in December 2008, Ukrainians remained opposed to NATO membership by a margin of two to one after the Bucharest summit, where NATO declined to offer Ukraine a MAP.

The 2008 NATO Bucharest summit’s communiqué welcomed Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations and acknowledged their contributions to NATO operations. It emphasized that both countries had made valuable democratic reforms and expressed support for their applications for MAP.

“Allies made clear that they support Georgia’s and Ukraine’s applications for MAP,” stated the communiqué. “NATO will now begin a period of intensive engagement with both countries at a high political level to address the questions still outstanding regarding their MAP applications.”

It reiterated that NATO's door remains open to European democracies willing and able to assume the responsibilities and obligations of membership. However, it did not specify a timeline for Ukraine and Georgia’s accession.

It’s important to note that a May 2008 Gallup poll showed that Ukrainians had doubts about NATO. NATO considers public support a critical requirement for membership.

After 2008, Ukraine’s domestic politics shifted. President Yanukovych (elected in 2010) dropped NATO membership plans and pushed for neutrality.

“Ukraine will continue developing its relations with the alliance, but the question of membership is being removed from the agenda,” said Kostyantyn Hryshchenko, Ukraine’s Foreign Affairs Minister, according to the Russian state-owned Interfax news agency. Russia welcomed this. NATO cooperation slowed but didn’t stop completely.

2014: Ukraine’s pursuit of NATO membership after the Russian invasion

In November 2013, people gathered in Kyiv’s Independence Square (Maidan) to protest after Ukrainian President Yanukovych rejected a deal with the EU. The protests kept growing and continued into February 2014.

In February, violence erupted between protesters and riot police. Over three days, more than 80 people were killed and hundreds were injured. Protesters defended themselves with sticks, rocks, and firebombs, while police used live ammunition and snipers.

Yanukovych fled Kyiv on February 21, 2014. Parliament removed him from office the next day and called for new elections. Soon after, Russia invaded and seized Crimea in late February 2014, then fueled armed uprisings in the East of Ukraine, turning entire cities into battlefields. By late 2014, fighting had devastated towns like Donetsk and Luhansk, killed thousands of civilians, and displaced over a million people.

This transformed Ukraine’s security policy. Ukraine turned to NATO for defense cooperation and military training. In response, NATO suspended most practical ties with Russia in April 2014, though channels for political and military dialogue stayed open.

Russia took control of Crimea and parts of the East of Ukraine in 2014 because Putin saw a chance to expand Russian power and keep Ukraine under Moscow’s influence. Russia wanted to keep its Black Sea Fleet based in Crimea and feared a pro-Western government in Kyiv might end the lease for Russia’s naval base in Sevastopol.

In 2014, Russian forces invaded Crimea, while Moscow poured its troops and weapons and backed separatists in the east of Ukraine as part of a broader plan to divide the country and gain control. Crimea remains a key base for Russia’s military power in the Black Sea and a launchpad for Russian attacks against Ukraine’s mainland. This invasion made joining NATO an even more urgent goal for Ukraine’s security.

Support for NATO in Ukraine rose to nearly half the population in 2014, surpassing those who were against or unsure for the first time. In 2021, 47.8% supported joining NATO, while 32.4% opposed it. Back in 2014, Ukraine also officially dropped its non-aligned status.

2016-2022: Ukraine aims to join NATO and amends its constitution

In 2016, NATO planned to send more troops to Eastern Europe, specifically Poland and the Baltic States, to reassure those countries after Russia’s attempted annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its continued aggression in the east of Ukraine. In response, Moscow said it would form three new military divisions near its western and southern borders and warned it might take further steps if NATO continued building up forces so close to Russia.

At that time in 2017, NATO’s leaders, including NATO’s ex-Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, stated, “What we saw in Crimea and Ukraine was that there was a lack of a strong military presence that made it possible for Russia to act in the way they did, with hybrid warfare, with little green men in Crimea.”

Ukraine made serious strides toward meeting NATO’s membership requirements, pushing for military and political reforms. In 2017, Ukraine passed a law declaring NATO membership as a strategic foreign policy goal, meaning future Ukrainian governments were now legally required to pursue or maintain that goal. In 2019, it was included in the Ukrainian Constitution as the country’s official foreign policy objective.

Despite his anti-NATO rhetoric, Putin never seriously feared a NATO military attack on Russia. Russian military reforms since 2000 have not focused on building large defensive forces on NATO’s borders. Instead, Russia sent its best NATO-facing units to Ukraine in 2021 and 2022, and even during peak anti-NATO rhetoric in 2023, Russia kept moving troops and gear from its NATO borders to the Ukraine front, asserted the ISW.

2021: Russia’s NATO demands

Russia publicly demanded that NATO cancel its promise made back in 2008 that Ukraine and Georgia could one day join the alliance in December 2021.

Russia also asked NATO and the US to promise not to place certain weapons near Russia, to restart regular defense talks, to limit where each side holds military drills, and to avoid dangerous encounters between ships and planes, especially in the Baltic and Black Seas.

NATO and the US immediately rejected Russia’s main demand. Jens Stoltenberg, said, “It is the Ukrainians, and only the Ukrainians, who can decide when there are conditions in place for negotiations and who can decide at the negotiating table what is an acceptable solution.”

Putin’s repeated breaches of agreements and outright lies only reinforced that Russia’s military aggression makes it an unreliable partner.

2022: Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine

Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, claiming NATO’s closer ties with Ukraine were a threat—the closer ties that were forged due to Russia’s own aggression starting in 2014. Since then, NATO countries have sent Ukraine weapons, training, and other support, but Ukraine is still not a NATO member. In September 2022, Ukraine officially asked to “fast-track” its NATO membership. NATO says it supports Ukraine joining one day, but there is no set date yet.

Russia’s military posture for years showed no serious preparation to defend against a NATO attack. Key defensive units were instead deployed inside Ukraine. Kremlin officials repeatedly claimed that NATO expansion endangered Russia, yet these narratives often contradicted each other and shifted to fit different audiences.

Putin’s real aim was never to block NATO but to restore Russian dominance over Ukraine and reassert Moscow’s control in its perceived sphere of influence. Ukraine’s NATO membership had been talked about since 2008, but in early 2022 it was no closer than before.

The West refused Putin’s ultimatums, demands that would have forced NATO to abandon its open-door policy and Ukraine to give up its sovereignty.

Olaf Scholz assured Putin that Ukraine would not join NATO, “in the next 30 years” just days before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Many facts point to the fact that Russia has used NATO as a pretext since the USSR and the creation of the Warsaw Pact.

In Putin’s view, wiping out Ukraine’s independence is key to undoing the Soviet Union’s collapse and rebuilding a greater Russian empire. He has pushed this vision with growing force since Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution and today is closer than ever to making it a reality.

The Hague Summit and Europe’s growing defense of Ukraine

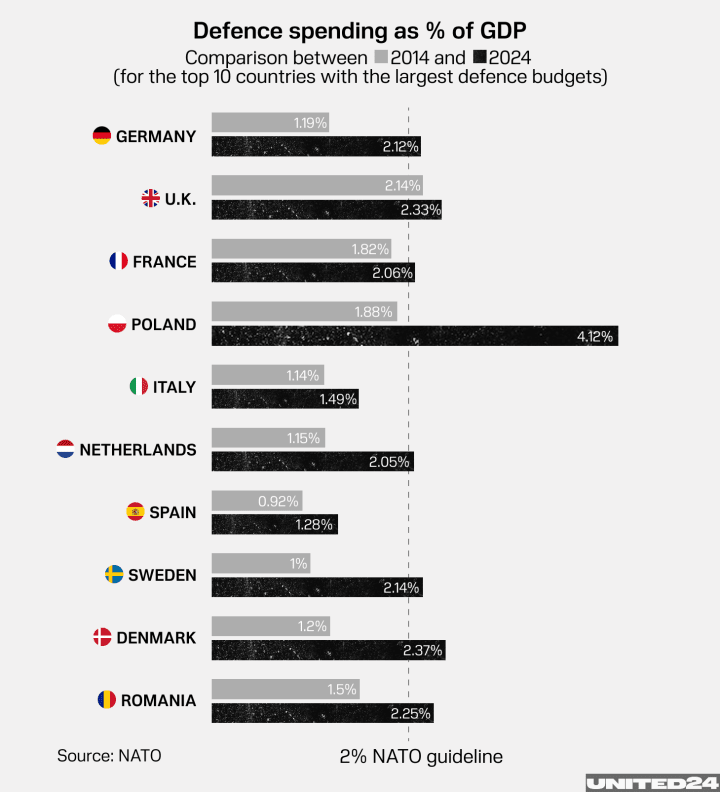

NATO officially announced its new 5 % GDP defense spending target at the 2025 Hague Summit, held from June 24–25 in the Netherlands. There, NATO announced it is set to raise defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035—up from just over 2%.

In response to Russia’s growing threat, with its war in Ukraine grinding into a third year, Western leaders are increasingly alarmed by a battlefield that now stretches far beyond the front lines, and by rising concerns of a possible wider war in Europe by 2029–2030. “Danger will not disappear even when the war in Ukraine ends,” said Mark Rutte, the NATO Secretary General in a speech in London on June 9.

Moscow’s strategy to undermine Western resolve blends cyberattacks, disinformation, economic pressure, and political subversion—reaching deep into Europe and beyond. The move, long pushed by the US (which still covers over 80% of NATO defense spending), aims to ease reliance on Washington, especially as US focus pivots toward Asia and Israel.

Despite economic headwinds across Europe, member states have increased support for Ukraine: in early 2025, European military aid surpassed that of the US for the first time since 2022, $83.75 billion to $75.44 billion. Sweden, Norway, the UK, France, and EU bodies have all contributed record sums.

For Ukraine, NATO’s new spending target of 5%, which is set to be announced at the upcoming Hague summit, signals lasting support and a critical morale boost.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-e5e2358f676d2926947b90a73136b91d.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)