- Category

- Anti-Fake

Ukraine is a State Actively Fighting Corruption, That’s Why You Hear About it So Much

When it comes to Ukraine, people still often mention major corruption scandals. Could it really be that, even amid an existential war, this country remains mired in corruption? Or perhaps all these high-profile cases actually signify something else?

Consider the trial of Ukraine’s Chief Justice. Or the charges against a Deputy Prime Minister. Or the investigation into the head of the Antimonopoly Committee. All of these are recent examples of Ukraine’s anti-corruption efforts.

Sounds like a country consumed by corruption? More like a country that is finally fighting it.

That is because when judges, ministers, and MPs are caught and prosecuted for abusing power, that’s not evidence of a failed anti-corruption system; it’s proof that it’s working. When you hear someone cleaning their home, it doesn’t mean their house is filthy. It means they care about keeping it clean.

According to a report from the influential Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), corruption in Ukraine is a well-known problem precisely because it is being fought.

Top score in OECD anti-corruption policy and institutions

OECD experts awarded Ukraine a score of 91.9 out of 100 in 2025 for its anti-corruption policy as part of the fifth round of monitoring under the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Plan. This marks one of the highest ratings among all participating countries and represents a substantial improvement from the 2023 assessment, when Ukraine scored 53 points.

The assessment evaluated Ukraine’s anti-corruption system across nine key areas, with anti-corruption policy ranking one of the highest, with an anti-corruption institutions' score of 92.7 and whistleblower protection scoring 90.2.

Key achievements include:

The development and effective implementation of the Anti-Corruption Strategy and State Anti-Corruption Program, grounded in in-depth analysis;

The introduction of a modern coordination, monitoring, and evaluation system for anti-corruption policy, with extensive public involvement;

The launch of an advanced information platform for tracking the implementation of state anti-corruption measures, enabling interagency cooperation and real-time progress monitoring.

In a special report released this November, the European Commission underscored Ukraine’s firm commitment to European integration and its consistent progress on reforms, despite the ongoing war.

The number of indictments and final verdicts in cases brought by Ukraine’s anti-corruption bodies has increased, European officials noted. The European Commission said that Ukraine must continue to strengthen its anti-corruption system and prevent any backsliding from the significant progress it has achieved in reforms.

Institutions that set precedents

Ukraine’s anti-corruption system was built from scratch. To make it truly independent from political power, after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, the country created a new architecture for fighting corruption:

National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) — investigates top-level corruption;

Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO) — prosecutes such cases in court;

High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) — delivers verdicts in cases involving senior officials;

National Agency on Corruption Prevention (NACP) — responsible for prevention: asset declarations, lifestyle monitoring, and integrity policies.

Other institutions also play a role: the Bureau of Economic Security, the Security Service of Ukraine, the National Police, the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA), along with numerous NGOs and investigative journalists.

Each body has its area of focus—together they form an ecosystem for detecting, investigating, prosecuting, and punishing corruption. As a result, people who once considered themselves untouchable no longer are.

In 2023, NABU detectives and SAPO prosecutors exposed the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice for taking a $2.7 million bribe in exchange for a favorable ruling. The case is now before the High Anti-Corruption Court.

Recently, Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Agriculture, and current head of the Antimonopoly Committee were charged. Other defendants include MPs, judges, and top officials from the Customs Service, Tax Service, and Ministry of Defense.

As of mid-2025, NABU and SAPO have identified 365 suspects, filed 696 indictments, and charged 1,429 individuals. The High Anti-Corruption Court, established only six years ago, has already issued over 300 verdicts.

But perhaps the biggest shift lies not in quantity but in quality—even the most senior officials can no longer expect to escape justice.

Independence and public trust

Independence is key for any anti-corruption agency in the world. In Ukraine, that independence is guaranteed through complex selection processes involving international experts.

Foreign representatives have a decisive vote in selecting the heads of NABU, SAPO, the High Anti-Corruption Court, and the Bureau of Economic Security. This mechanism proved its effectiveness in 2025, when international members of the selection commission blocked attempts to manipulate the competition for the bureau’s director.

According to the OECD, this level of external oversight doesn’t exist even in some EU countries. They say that this has strengthened Ukraine’s system against political pressure.

But support also comes from below. According to NACP data, the public’s willingness to report corruption has reached a historic high—partly thanks to reforms protecting whistleblowers. Ukraine scored 90.2/100 in this area according to the OECD.

In 2024, two ordinary citizens received a total of ₴15 million (over $350,000) in state rewards for exposing corruption. In one case, a Defense Ministry employee reported a ₴24 million bribe offer. In another case, individuals tried to bribe NABU and SAPO leaders with $6 million to close a case against a former environment minister.

Similar whistleblower reward programs exist in the US and South Korea, but Ukraine’s approach is exceptional in Europe. Soon, 92,000 organizations across Ukraine will be connected to the national whistleblower reporting platform.

Another key transparency measure is asset declarations. A special online system allows officials to file, verify, and publicly disclose their assets. About 700,000 declarations are submitted annually.

The OECD calls Ukraine’s declaration system “one of the most advanced in the region: comprehensive, transparent, fully digital, and supported by automated verification software.”

But there’s another way to combat corruption: eliminate the opportunity for it.

The digital revolution

In the past, a citizen might have paid a bribe to speed up paperwork or influence an official’s decision. Now, there’s simply no one to bribe—most administrative processes are automated and completed in just a few clicks.

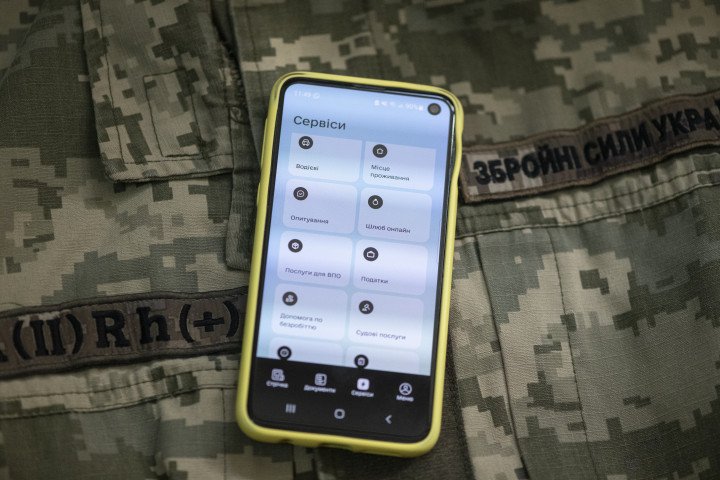

The Diia platform lets people instantly access documents, social benefits, business registration, and car ownership services. You can’t bribe an algorithm—and you don’t need to, because the process is fast and transparent.

The Helsi medical system allows patients to book appointments without envelopes of cash or mysterious waiting lists.

Thanks to the Kyiv Digital platform, the capital is now among the world’s top 15 most digitalized cities.

By digitizing government-to-citizen interactions, Ukraine has sharply reduced opportunities for petty corruption.

In public procurement, the Prozorro platform ensures that all government tenders are open and transparent. While it doesn’t eliminate abuse entirely, it makes it visible. In the first 8 months of 2025 alone, more than 1 million procurements worth over ₴500 billion ($1.2 billion) were conducted via Prozorro, saving 10–15% through competition. Journalists and NGOs can monitor contracts in real time. It was through Prozorro that they uncovered the infamous “egg scandal” in the military supply system, leading to major reforms in defense procurement.

The public outcry that followed was enormous — another sign of progress.

Fighting corruption is a process, not a state

Ukrainian society has long ceased to be a passive observer. When courts acquit high-profile defendants, citizens protest. When authorities try to undermine anti-corruption bodies, the public pushes back.

Since 2014, a powerful civic anti-corruption sector has emerged, consisting of investigative journalists, watchdog organizations, and activists who force the system to work.

According to the OECD, Ukraine’s anti-corruption policy score rose from 53 in 2023 to 91.9 in 2025, while institutional capacity increased from 78.6 to 92.7. Transparency International also notes steady improvement in Ukraine’s Corruption Perceptions Index, even during full-scale war.

“Ukraine has made significant progress in fighting corruption despite the challenges of Russia’s full-scale invasion,” the OECD notes. “Key achievements include launching a modern, inclusive system for monitoring anti-corruption strategy, advancing whistleblower protection, and ensuring formal independence for the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office.”

Ukraine doesn’t hide its problems. Most anti-corruption institutions publish open statistics and public reports, and independent investigators have large followings. Journalists cover every crime and punishment. That doesn’t erase all issues—but it builds transparency, without which progress is impossible.

Once, Mezhyhirya—the lavish estate of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych—symbolized elite corruption and impunity. Today, it’s open to all citizens.

The transformation of that very place says more than any statistic: a former symbol of corruption now serves the public.

Ukraine is not a corrupt country. It is a country fighting corruption.

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)