- Category

- Culture

The Restoration of This Garrison Church in Ukraine Reveals What the Soviet War on Religion Tried to Bury

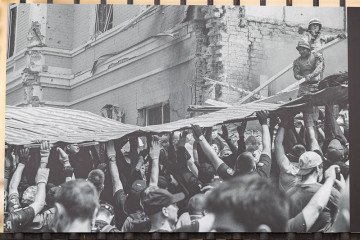

When Ukrainian restorers found a centuries-old sculpture of Jesus wrapped in a massive canvas and hidden in a war-damaged church, they didn’t just uncover a relic, but a legacy of resistance. Just as someone once hid it from the Soviets, Ukrainians today are racing to protect their heritage from Russian bombs in the very same spirit.

In the western Ukrainian city of Lviv, the Saints Peter and Paul Garrison Church is a living monument to Ukraine’s endurance. We visited the church to document what was uncovered and what’s still being restored—all documented in photos.

A sanctuary for the defenders

Once nearly lost to neglect, the church has been painstakingly brought back to life through a remarkable partnership between Ukraine and Poland — a reflection of the deep historical ties between the two nations and a shared vision to preserve their common heritage.

Garrison churches have always been more than just places of worship, even if originally built to serve the military. They offered blessings before deployment, comfort for families left behind, and a spiritual home for soldiers and their communities.

In wartime Ukraine, the tradition has only deepened. Today, the Saints Peter and Paul Garrison Church in Lviv holds hundreds of funerals for Ukraine’s fallen, mourning those who gave their lives defending their country against Russia’s invasion. Its doors and chaplains remain open to civilians, troops, and all who seek solace within its baroque walls.

Across the country, churches haven’t just been places of mourning — they’ve been targets. Hundreds of religious buildings, from the UNESCO-protected Transfiguration Cathedral in Odesa to the century-old Saint Nicholas Cathedral in Kyiv, have been damaged or destroyed by Russian shelling.

In response to the cultural threat, Ukraine has moved quickly to protect its most vulnerable landmarks: boarding up stained glass, sandbagging entrances, and evacuating icons before they can be a part of the rubble.

The long road to restoration

Built between 1610 and 1730, Saints Peter and Paul Church was the first fully Baroque church constructed in Eastern Europe in its authentic style. At its completion, it could hold nearly 3,500 worshippers, almost half of Lviv’s entire population at the time.

Situated just beyond the old city walls and the Poltva River, which now runs underground beneath Lviv’s central street, the church was oriented toward the old town center, not the main square. It’s a strange detail that still holds true today.

"This church holds great historical importance," Father Taras Mykhalchuk, a bishop and rector of the Garrison Church, told UNITED24 Media. "It was built just outside the city's defenses. Many people don’t realize that remnants of the old wall still exist nearby."

The church’s interior boasted extraordinary frescoes by Moravian painter Franciszek Ekstein, using illusionistic techniques to create a soaring, dreamlike space 26 meters above the ground

After World War II, the militantly atheist Soviet regime closed the church in 1946. Its doors remained shut for over half a century, and the church's condition deteriorated. At one point, the building stored nearly three million books as part of the Stefanyk Library archive.

“Worst of all, the church went without a roof for at least twenty years,” said Father Taras. “Only the brick vaulting provided some protection, but the roof had been completely destroyed by fire. Moisture seeped into the vault structure, causing extensive damage, especially to the frescoes.”

The prolonged exposure led to severe deterioration — but fortunately, it wasn’t beyond repair. Ironically, the millions of books stored inside may have helped preserve parts of the structure by absorbing much of the moisture.

What was found hidden inside

Though the Saints Peter and Paul Garrison Church had fallen into near ruin, it was never forgotten. Thanks to the dedication of scholars and the deep historical ties between Ukraine and Poland, help was on the way. Leading the restoration was Dr. Paweł Boliński, a renowned Polish art conservator and Baroque wall painting expert known for his work across Central and Eastern Europe.

"Archival records — particularly a book we have — show how the church once looked," recalled Father Taras Mykhalchuk. "Thankfully, the original plans were preserved in Polish archives."

Those documents, along with early site visits, revealed the magnitude of the task ahead. Years earlier, while attending a conference in Lviv, Dr. Boliński had managed to access the then-closed church.

"Inside, towering bookshelves filled the space, and in the dim light high above, faint outlines of paintings could be seen — already in very poor condition," he remembered. "I thought immediately: what a fascinating conservation challenge it would be to save those paintings."

When the church was returned to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in 2011, a team of Ukrainian and Polish specialists quickly organized it, with support from the Polish Ministry of Culture, the Małopolska Voivodeship Office, and additional grants. The city of Kyiv funded part of the restoration of the exterior façade.

"Our first steps involved inventorying the entire interior and conducting deep research," Dr. Boliński explained. "Conservation work must be preceded by thorough interdisciplinary study — understanding the paintings' history, techniques, secondary layers, and state of preservation."

Only then could restoration begin, starting with the presbytery vaults and moving into the main nave. The frescoes inside, painted by Franciszek Ekstein in the 1740s, were in catastrophic condition.

"Later restorations had damaged the original character of the frescoes almost beyond recognition," said Dr. Boliński. "We had to carefully remove layers of overpainting, stabilize the surviving sections, and reconstruct missing parts."

For eight years, the original illusionist decoration, designed to make the ceiling appear as an open sky, was painstakingly uncovered and preserved.

For Father Taras, the restoration revealed the hidden scars left by decades of Soviet neglect.

"We made discoveries almost daily," he said. "Many structural changes were made arbitrarily — doors bricked up, access routes closed without care for the church’s heritage."

One of the most extraordinary finds came during the removal of books.

"We noticed what looked like a body wrapped in golden cloth," Father Taras recalled. "The cadets helping us thought it was human. But when we unwrapped it, we found a large 18th-century sculpture of Jesus Christ, preserved inside a six-meter-tall canvas painting of Saint Benedict." Both artifacts have since been returned to their former glory and are now proudly displayed in the church.

Why the church still matters today

The Saints Peter and Paul Garrison Church is fully open today. Its restoration is still a work in progress, but its doors remain wide open to soldiers, families, and a country at war. The most critical phases of the conservation effort, including the frescoed vaults and the presbytery, have been completed. What remains is the restoration of the 18th-century Baroque high altar, a project slowed but not abandoned by the realities of wartime Ukraine.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, cultural preservation became a second battlefield. Conservators across Ukraine, including in Lviv, moved quickly to protect what they could.

"Wartime is a very particular period in which art conservators can play a crucial role," said Dr. Pavlo Boliński. In Lviv, stained glass windows were boarded up, altars shielded, and sacred furnishings moved to safety — acts carried out quickly, before the worst could reach them.

The Garrison Church wasn’t preserved for its age or architecture. It was preserved because it’s where the war keeps arriving — in funerals, in silence, in the faces of families who come to bury someone they love. It’s where the country remembers what it’s fighting for.

"Today, the Garrison Church and its clergy have become a leading center not only for religious life but also for culture in Lviv," said Dr. Boliński. "Its status as a garrison church highlights its role in building Ukraine’s national identity — a role that will only grow stronger in the future." Even under missile threat and wartime pressure, restoration work continues, preserving the church not just as a monument, but as a living part of the country’s cultural and national life.

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)