- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Back From Hell: The Emotional Return of Ukrainian Soldiers From Russian Captivity

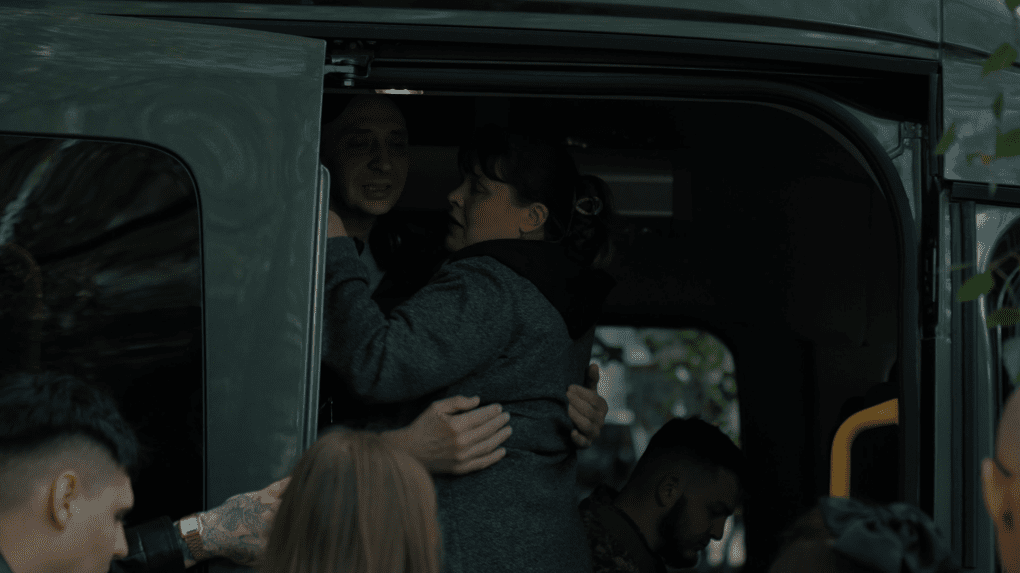

A group of men draped in blue and yellow flags steps off the bus into a crowd. “Welcome back! Thank you, guys!” echoes from all sides. Moments later, a woman runs in to embrace one of them. This is one of the places Ukraine’s former prisoners of war are brought after exchanges, with more defenders returning from Russian captivity on June 19.

Among the cheers, a repeated shout can also be heard: “Have you seen this person?”

Reuniting after Russian captivity

“What are you studying?” a man asked one of his two daughters, hugging his family. “Geography? And what about you?” he turned his face to the second one. The other girl is studying economics. These updates are among those he missed out on while in Russian captivity, as the last time he saw his loved ones was months ago.

However, these short meetings don’t last as long as family members would like. A car is already waiting to take him to the hospital for a full medical examination. As soon as the door closes, his wife quickly opens it again to hug the man she loves one more time. This is an opportunity she hadn’t had for almost 40 months.

At the same site, another family is reunited: a woman, Liudmyla, with her brother. “He never lost heart. He encouraged me during difficult moments in my life, and I also tried to encourage him. I had faith.”

Liudmyla has been waiting for her brother Oleksandr to return from Russian captivity for more than a year, since April 2, 2024. Finally, today, she welcomed him home.

“When he went to war, he must have truly felt that’s where he belonged—because they formed another kind of family there,” she said.

While Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of the Prisoners of War does not share the numbers of returned, it’s known that many of those released were defenders of Mariupol and had spent more than three years in Russian captivity. All of those returning suffered severe injuries and continue to battle chronic health conditions caused by their wounds and the harsh conditions of their confinement.

“I want this damned war to end as soon as possible, and for everyone to welcome home their brother, son, husband, or father—and to feel the emotions that I’m feeling right now”, Liudmyla underscored.

Have you seen this person?

The walls near the entrance of the building are covered with photos of the Ukrainian soldiers. Photos are also in the hands of the many gathered to greet the released defenders. While the Russian side doesn’t share official information about Ukrainian prisoners of war, these people are hoping to hear at least something about their loved ones from those who returned.

“Guys, is anyone from Mordovia ?” a woman asks the ex-POWs as they pass her. On the other side of the building, another woman explains to a Ukrainian soldier she saw in the window: “My brother is a Marine. Maybe you've heard of him? He’s from the 38th Brigade.”

For Oleksandr, this is not his first time at the exchange site. “When I found out that this is where they bring them [defenders—ed.] during exchanges, I started coming here.” The man, who lives 100 km away, is looking for his son, 39-year-old Yurii, who went missing in November 2023 in the Kharkiv region. Since then, the father has received no information about him. “They went to the position,” he said. “My son was the group leader. He left his group in one trench to go to another to bring the commander some batteries for the radio.”

However, Yurii’s brothers-in-arms say that at the moment he got there, the position had already been overrun by the Russians. “He shouted to the others: ‘My leg is injured—I’ll cover you.’ An artillery strike began. And that was it.”

A woman, Yuliia, is standing in the crowd. She came from Odesa, and just like Oleksandr, this is not her first time here. Searching for her older 24-year-old brother, Mykhailo, she explains that when her family heard that some of the released might recognize a person in a photo, they started asking about him. “Unfortunately, he hasn’t been seen”, she said. Mykhailo went missing in the Donetsk region. “We were informed that a battle had started in the area where they were. We asked—was there a chance they were captured? We were told: ‘Yes, as no bodies had been found.’ Drones were sent in, but there were no signs of the guys’ bodies. We were told to hope for the best.”

Yuliia is surrounded by children, evidently because of a puppy she brought along with her. A small dachshund named Marsyk, a surprise for her brother. “He really wanted a purebred dog—and we decided to fulfill his wish. It will be a little stress-reliever for him.”

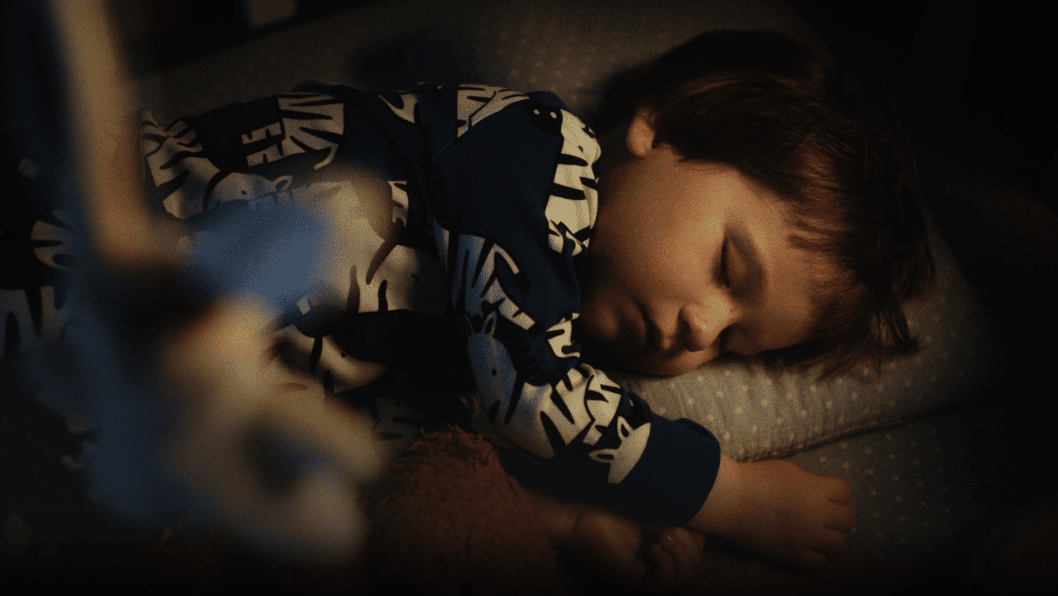

Among the children playing with Marsyk is Davyd, who is here with his mother, Violetta. Originally from Berdiansk—the city now occupied by the Russians—they moved to Odesa. Both Davyd’s father and godfather have been in Russian captivity for 38 months, since they were captured in Mariupol.

“My husband is being held in Sukhodilsk , and his brother is in Mordovia,” says Violetta. “His brother’s wife received a letter; as for me, I only heard from the guys who passed on a message from captivity—that he loves us very much. I wrote him a letter, more than one, but they never reached him. Letters are not allowed there.”

On Violetta’s phone case, we see the last family photo taken before Russia’s full-scale invasion. Back then, Davyd was only three months old. This September, he’ll turn four.

The silence on the Russian side

“We never have any official information about numbers or health conditions of Ukrainians in Russian places of detention,” said a representative of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Petro Yatsenko. The Ukrainian side has to get this kind of data from other sources, he said.

“Here we have a POW who lost almost 60 kg,” said Yatsenko. “Another one was beaten in Russian captivity. He lost the ability to walk. It's the way they are treated in Russian places of detention.”

Over 95% of Ukrainians released from Russian captivity experienced torture such as beatings or lack of food, or medical care, said Yatsenko. They are also placed in full isolation.

“We need international organisations, like the International Red Cross, to have the opportunity to visit all Russian places of detention to inspect real conditions there,” says Yatsenko.

More than 70,000 people were listed as missing in the Unified Register of Persons Missing in Special Circumstances as of May 2025, reported Ukraine’s Commissioner for Persons Missing Under Special Circumstances, Artur Dobroserdov, in an interview with Ukrinform.

Yatsenko underlined: they are working for all Ukrainians who are in Russian captivity—both military and civilian—to come back home: “A lot of Ukrainians are still in Russian captivity, and we are working hard to release them, to give these families more hope and chances to see their loved ones’ eyes.”

Wounded Mariupol defenders returned home after over three years in Russian captivity to emotional reunions. pic.twitter.com/45dev4Hp1C

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) June 19, 2025

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)